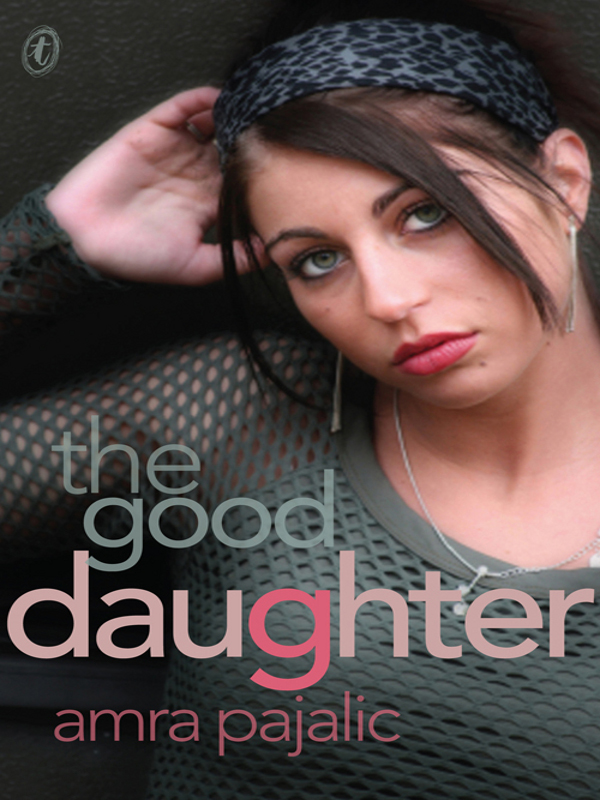

The Good Daughter

the good daughter

Amra Pajalic was born in 1977.

The Good Daughter

is her first novel. Her short stories âSiege' and âF**k Me Eyes' have appeared in the 2004 and 2005

Best Australian Short Stories

.

The Good Daughter

was shortlisted in the 2007 Victorian Premier's Award for an Unpublished Manuscript by an Emerging Writer. She lives in St Albans, Melbourne, with her husband, daughter and three cats.

Â

the

Â

good

daughter

Â

a novel

amra pajalic

Text Publishing Melbourne Australia

The paper used in this book is manufactured only from wood grown in sustainable regrowth forests.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

www.textpublishing.com.au

Copyright © Amra Pajalic 2009

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by The Text Publishing Company 2009

Cover design by WH Chong

Page design by Susan Miller

Typeset by J&M Typesetting

Printed and bound by Griffin Press

âPediculus Pubis' by Bijelo Dugme

Music/lyrics: (Bora /Goran Bregovi

/Goran Bregovi )

)

Album: Bijelo dugme: Bijelo dugme

Publisher: (Kamarad - Diskoton, 1984)

Every effort has been made to trace the original source material contained in this book. Where the attempt has been unsuccessful the publisher would be pleased to rectify any ommision.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Pajalic, Amra.

The good daughter / Amra Pajalic.

ISBN: 9781921520334 (pbk.)

For secondary school age.

A823.4

To my husband and daughter

Contents

boys will be boys, will be girls, will be boys

the secret life of wonder woman

what comes around, goes around

to err is human, to forgive divine

âYou can't go like that!' Mum gasped. She pushed me back into my bedroom. We were going to a

zabava

, Bosnian for a party.

Zabavas

were organised twice a year, once as a community meet-and-greet, and also to celebrate

Ramadan

, the Muslim religious month of fasting. This would be my first

zabava

.

âWhy not?' I demanded, my hands on my hips as I twirled. I was wearing the little black dress Mum bought for my fourteenth birthday. I'd grown in the last year and the dress moulded to my body. I'd worn it a few months before, when we attended a work barbecue for Dave, Mum's ex-boyfriend. Mum had complimented me then.

âIt's not suitable, Sabiha,' Mum protested now, as she rifled through my wardrobe.

Although both my parents were from Bosnia, I didn't have anything to do with the community. When I was six years old, Mum and I moved to inner-city Thornbury. Now that I was fifteen we were back where we'd startedâin St Albans, âSh'nawb'ns', we say.

Even though St Albans was established in 1887, at least that's what the plaque at the train station says, you can't tell by walking through the bustling centre. The buildings are two-storey plain block structures with tin roofs. The shopfronts reveal a mix of Europeans, who settled after the post-World War II boom, and Vietnamese who came in the 1970s.

The suburb has few distinguishing features: streets that form perfect rectangles, an absence of trees on nature strips, and the fact that every second shop is a pharmacy catering to the ageing population.

There were always Yugos in St Albans. After the Balkan War in the early 1990s, the population exploded with refugees settling there from all over Yugoslavia. It wasn't a coincidence that Mum and I moved away just when the refugee onslaught moved into St Albans.

I never thought of myself as Bosnian. I was born in Australia, my friends were Australian and, if I thought about it at all, I would have called myself a true-blue Aussie. All that changed three months ago.

âWhat's wrong with my dress?' I admired myself in my wardrobe mirror.

âYou're too, too...'

âBeautiful, hot, gorgeous, sexy.' I cocked my hip. The black dress brought out the highlights in my dark-blonde hair. The V-neck showed off my cleavage, while the mini-skirt made my legs look longer.

My bedroom door was pushed open. â

Hajmo

!' My grandfather was hassling us to hurry up. He caught a glimpse of me. â

Bože saÄuvaj

,' he hissed, âGod save us,' and turned away.

â

Bahra, nadji joj nežto drugo da obu e

e

!' His abuse came in rapid-fire bursts. All I understood was that he wanted Bahra, my Mum, to find me something else to wear; that people would think the worst if they saw how I was dressed; that I was a whoreâ¦then I lost the rest of his tirade.

âDid Dido call me a whore?'

âHe said you look like a whore with that make-up.'

My grandparents were supposed to have come to Australia in 1995, after the Balkan War, but my grandmother's diabetes made her too ill to travel. When she died last year, my grandfather came to Australia and lived with Mum's sister, my Aunt Zehra, Uncle Hakija and their children, Adnan and Merisa.

Unfortunately for me it was only a few months before Uncle Hakija and Dido couldn't stay under the same roof. Auntie Zehra manipulated Dido into leavingâapparently by telling him that Bahra needed to be with him after all these years. And then she served up a good dose of guilt to her sister about being the black sheep, and about all the embarrassment Mum caused by shacking up with an Aussie. So Mum caved in and she and I made the move back to the western suburbs. And Dido moved in with us. 2008 was the year my life became hell, thanks to him.

I checked my make-up in the mirror. My foundation was flawless, my pale skin blemish-free. The liquid eyeliner and eye shadow brought out my green eyes. I was wearing the basic make-up any teenage girl would wear out at night.

âHe's whacked, Mum.'

She glanced at my face. âYou'll have to tone it down.'

âBut I'm wearing regular make-up!'

âWe need to make a good impression.' Mum sighed.

âYou're saying we're not good enough?'

âNo.' Mum put her hands on my shoulders. âTonight is a very important night. It's the first time we're attending a Bosnian function as a family and we're all anxious about looking our best.'

I had to admit that tonight was Mum's night. After Auntie Zehra's family had arrived from Bosnia twelve years ago, we'd managed to play happy families for a total of two years, before Mum and her sister had a falling out. We hadn't had anything to do with each other during the ten years Mum and I lived in Thornbury. But tonight was The Reunion.

She hugged me but I held myself stiff in her embrace.

âI look great.' I pulled away from her, forcing her to look at me. âDon't I?'

Mum hesitated. âYes, you doâ'

âSo what are we waiting for? Let's go.' I headed for the door.

âBut this isn't an Australian party. This is a

zabava

. Everyone will be watching us, judging us, judging me.' Mum winced.

Mum and I weren't what you would call traditional Bosnians. More like exiles returning to the fold. Mum had made some bad decisions. At the age of eighteen, she married my father, who brought her to Australia in 1989. After my birth she had a nervous breakdown and went to hospital. My Dad left us a few months after I was born because he didn't want a mental for a wife; so Mum embarked on what I called her âFinding a Daddy' phase, when she dated every Bosnian man in sight, supposedly to find a father for me. Some lasted a night, some a week, some a few months, but inevitably they all left us. She ended up getting a bad reputation and this was one of the reasons why we moved out of St Albans.

âPlease Sam-Sabiha, be good for me. We need to find you a proper dressâ¦'

For years I'd called myself Sammie Omerovic and so had Mum. It was the easier option because most Australians had to be taught to pronounce the âh' in my name. And then there was the deciding incident.