The House of Dies Drear (19 page)

“No. No, this time you are wrong.” Mr. Small spoke evenly, hardly letting his voice rise above a whisper.

“You!” hissed Pluto. “You are a thief after all. You thought to fool me to get at this storehouse, but you’ll not do it. No, it’s mine to hold and to keep!”

“No, not yours,” said Mr. Small. “If any one of us were to tell, the foundation could come claim it at any time. They own all this land and these caves, too. It’s not yours, it’s no man’s.”

Mr. Pluto seemed to sink down into his shroud. He was still, breathing heavily. Mr. Small thought to walk near, to see if he were all right. He hoped the old man was all right; he gambled on the strength and will of decades to come hold the old man up now. He had no intention of destroying Pluto. He had meant only to somehow bring an end to his utter fear and dread. It was cruel, what he had said, for the cavern of Dies Drear should have belonged to Pluto, since Pluto alone had cherished it for so long.

“We mean not to steal one thing in this cavern,” said Mr. Small. “I mean that we want nothing here for ourselves. All we want to be sure of is that the Darrows or anyone else should never waste it. What would become of the fine tapestries, the great goblets and bottles, if one day some men bought this property and decided to dig deep for wells or what have you? Anything at all could cause all of this to be destroyed. Do you understand what I’m saying? At any moment, at any time, all of this could be buried forever!”

Slowly Pluto raised his head. “Buried?” he whispered. “Sell this … my land?”

“Not your land,” Mr. Small said. He held himself tight inside. He made his heart cold so he might speak what he felt he had to. “You are a squatter here, old man. You have been paid to be a grounds-keeper, and that is all you are here. You have no rights whatsoever.”

“No, not true,” said Mayhew. He came around Mr. Small and walked behind the desk where Pluto sat. He went to one of the cases that held the ledgers and old, rare books. Carefully he pulled down one large book, in which there was much handwriting on paper that was thick and deep brown.

“Here we have the last will and testament of Dies Drear,” he said. “Care to look at it, Mr. Small? Well, no need for you to. The man had some kind of premonition—like a prophet, he knew his time was near. And he willed this cavern and whatever was found in it to the first son of slaves that was able to find it. He knew no bounty hunters, nor any other white men, would ever find this cavern. For the one who found it would have to have been cut off from his past, his history, as were the slaves. He would have to find that past in order to find himself. It took my father some thirty years, but he found it.”

There was silence in which Mayhew handed the book to his father. Ever so carefully, old Pluto laid it atop the pile of ledgers on his desk.

“I wasn’t looking for this place, nor no treasure,” Pluto began. “You see, Mr. Drear built another wall in my cave where I live. Not the wall you see now, with the ladder and the rope hanging down. No, not

that

easy to find this. But he built a wall to look like any cave wall, with a bit of dye like a covering of seeping dirt, or maybe just a little grayness for to make it seem ordinary. How many years I stared at it because I had nothing else to look at! It was my picture screen, on which I placed my dream of finding something … I didn’t know what. Then I began to dream of finding something belonging to those who were sold and those who were brave and sold all the same.”

“Because your ancestor was one of the two slaves who died the week Dies Drear was killed—is that it?” asked Thomas.

“No,” said Mayhew.

“No, not the two slaves that was hunted and killed just the same as the old man,” said Pluto.

“But the one mentioned just once in all the history and the legend told of the house,” Mr. Small said. “There were

three

slaves caught the night two of them were killed.”

“The third slave!” said Thomas. “He got clean away!”

“He got away,” said Mayhew, “and he went far north, reaching Canada, where he lived and prospered until he died.”

“And his great-great-grandson came one day to claim all this,” Mr. Small said quietly. “Maybe he had heard some ancient tale about something hidden in this house. A tale that had been passed on from generation to generation, each time becoming less clear and more mysterious.”

“Yes,” Mayhew said, “but the slave who ran free wasn’t the only slave who ran free the time the house of Drear fell silent as a tomb. This cavern had at least one slave still resting within it. He could have been Mohegan, as the Darrows say. The bounty hunters who caught and killed two of the three running slaves and killed old Drear never had an inkling of this cavern. They never even found that first cave. But at least one slave had to be in here. When he, too, ran free, he told a tale of hidden wealth, which, as you say, Mr. Small, became distorted through generations of telling. By the time River Swift hunted the house of Dies Drear, what he looked for was hardly more than a wish.”

“You’ve got to try to understand,” said Pluto. “River Swift, he wasn’t so awful bad. He was my companion when we were young. We shared the dark and dank of the tunnels—our footsteps together made hardly a sound on those ghostly paths. I suppose in the beginning he hunted for himself, the same as I did. But always he was a greedy boy, greedy to have and greedy to take. I reckon he got to thinking hard about old Mr. Drear dying wealthy as a king. So over the years, what he hunted got changed into a stake of glitter all for himself. By the time his manhood came, he knew there was a treasure of gold some place. He would have laid out his footsteps on my back to get to it, too. But you shouldn’t blame him to his soul. We both lost, he and I. We both did lose …”

“So then,” said Mr. Small, “we have all of it now.”

“But listen,” Mayhew said softly, “let him tell it—it has been so long that he couldn’t tell it.”

And Pluto told them, his voice going back to that hopeless time.

“After the boy and his mother had picked up and gone,” Pluto said, “I had nothing to look at but that wall, night after night and year after year. Until one time, I got so I couldn’t stand to look at it. So I got me some paint and I was going to paint the whole cave white. I started with that wall. I painted the whole wall that night and then I went to sleep, glad I had done something to take my mind off the tunnels. I had walked them so often, finding things—clues, bits and pieces of the cross… .”

“Like this cross?” said Mr. Small. He produced the four triangles he and Thomas had fitted into a Greek cross. Very carefully, he put the cross in Pluto’s palm.

Pluto stared at it. “It’s just a one they will make to pretend with,” he said. “Them fool Darrows. The cross was handed down to them just like the tale of the Mohegan was. But they don’t know how to read it … they don’t know what’s it’s for. Just mindless, they will make the cross and stick around the triangles.”

“How do you read it?” asked Mr. Small. “How can you read from four triangles that are exactly alike, that can be moved to fit any angle of the cross?”

There was a pause in which Mr. Pluto’s fingers moved over the cross. He looked up after a moment and smiled at Mr. Small. “Old Mr. Drear surely did fool you with this one!” he said. He chuckled. “First, before I read it, you must tell me how you found it, Mr. Small.”

Mr. Small explained how he had found three triangles stuck in the doorframes inside the house and the last one in his office in the college tower.

“Thomas and I found that by moving them around, we could make a Greek cross out of them.”

“Surely you did,” said Pluto, “and that was your first mistake. Now wouldn’t you know Mr. Drear would figure out that folks, not knowing what they saw, would move a triangle when they came upon one? Wouldn’t you know he knew folks well enough to figure they would have to touch it, turn it over, hold it up to the light and turn it around? Yes! And he counted on them doing that.

“You can’t move a triangle from where you find it! You can’t move it if you want to

read

it!”

“So, not moving it, how do you read it?” asked Mr. Small.

“This was a cross reading for fleeing slaves,” Pluto said. “It was Mr. Drear’s own creation. It’s all written down and diagrammed in one of his books. He gave the crosses to the people who helped slaves from one hiding place to another. They were called the Conductors, I believe, and it was rare that a slave ever saw them. But a slave would find their crosses. And what he found weren’t fancy crosses like this one and others Darrows will make. Those a slave found might be made from twigs tied together and nailed up. Or even dead animals fixed on a tree trunk.

“The first thing a slave was taught about the cross reading was that he would never find a triangle laid flat—not on the ground or anywhere else flat. It wouldn’t read, because you could move around it, and if you could move around it, you couldn’t get the sense of it.

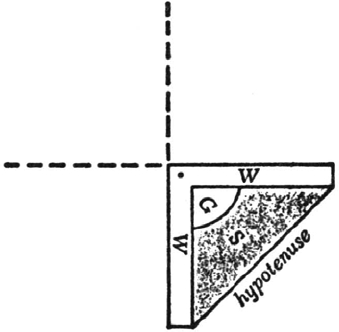

“The second thing a slave knew was that a triangle could be found on any object perpendicular to the ground—a cliff wall, a riverbank, a tunnel wall, a tree. Anything at all, as long as it was upright and stayed put. Then, when he found a triangle, he had to stand directly in front of it.

“The third thing a slave learned was never to touch a triangle he found. He was to stand directly in front of it, but never to touch it. If he touched it, he might change its position in some way and upset the reading.

“Next, he would imagine he could make two lines leading from the two legs where they made a right angle. And with his finger he would lengthen these lines until he had himself a cross. The place where the triangle he found fit on this cross would tell him where to go next.”

Mr. Small pulled out the paper on which he had drawn his first diagram of a triangle. With dotted lines, he extended the two legs of the angle until he had made a perfect cross.

“That’s it,” said Pluto. “That is how it was done.”

After a moment he continued. “The last thing a slave was taught was never ever tell the cross reading. Not to another slave, not to a freeman, not even to his kin. That’s why so few people ever heard about it. Slaves took the reading to their graves. That’s why, whenever I chance to pass a graveyard and see all them crosses, I can’t help but pause awhile, just looking.”

After a time Mr. Small spoke. “Please read for me now, Mr. Skinner, the metal and wood cross the Darrows made.”

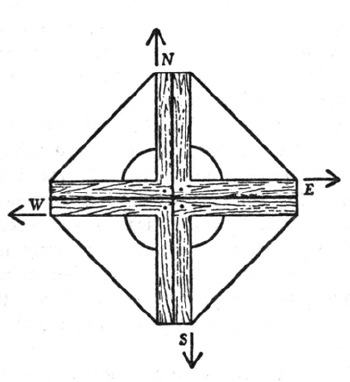

Pluto held out the cross in his palm. “This way, with the four triangles in place,” he said, “the cross reads nothing. But pull the cross apart and look at one triangle at a time … well then, each will read. Here.”

He pulled apart the four triangles. Then, using Mr. Small’s pen, he drew a cross on the side of one of the bookcases.

“Take the top triangle on the right side first,” he said. He slapped one metal triangle in place on the bookcase. The peg sank deep into the wood. “One leg points north, the other to the east. That means flee east from where you found it.

“Take the second triangle, the one on the bottom right,” he said. He slapped it in place. “One leg points south, the other to the east. Flight is south.”

He placed the top left angle on the outline of the cross. “It points north and to the west. You must flee north.

“And the bottom left angle will point south and to the west.” He placed it, completing the cross. “The flight is west.”

Thomas and Mr. Small stared at the finished cross with eyes that could see it as running slaves must have seen it.

“What a wondrous thing,” Mr. Small said, “to read freedom from so simple an object as a cross.”

“Yes. Yes,” said Pluto. “And a slave might find ten different triangles made from sticks, animals, even bits of rags, in one single night of running through woods, along streams, tunnels. Each time he came upon one, he would stand before it, make the outline of a cross and continue on.”

“I can see how he would know east or west,” said Thomas, “because that’s the same as going left or right. But how is it he would know which was north or south? On a vertical surface north would be up and south would be down on the ground.”

“Oh, Mr. Drear thought it all out,” said Pluto. “Up meant for a slave to go straight forward from the place he stood. And down meant he should turn around and head straight away from the place he had stood.”