The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (31 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

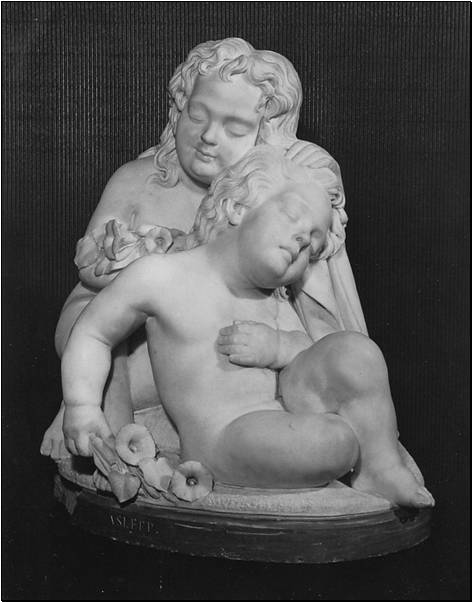

Italy’s new status as a modern nation gave birth to national pride and the desire to parade its best before the world. At a national exposition held in Naples in 1872, King Victor Emmanuel II gave Edmonia a first prize for

Asleep,

a pair of napping babes (Figure 33).

[466]

She proudly accepted the gold medal she wore at receptions for years. She also won a certificate of excellence for a toddling Cupid in

Love Caught in a Trap

(cf. Figure 34).

The Italian art world adored the pudgy tots, usually male and naked, that they called

putti

[Italian: boys]. Edmonia’s prize-winning touch made alchemy with marble. It turned the cold, inert stone into adorable baby fat, silkily expressing every sensuous ripple, finger, and toe. Indeed, confirmed by Italian judges and the sophisticated art committee of the Union League Club, her skills were entirely on a par with better-known sculptors of the day.

Unswerved by such triumphs, she continued her political interest. Noted by a German magazine, the following winter she exhibited in Vienna at a show themed on slavery.

[467]

Regrettably, we have not come across any detail to indicate what she showed. This aside, her last ideal work directly connected with slavery appears to be

Hagar.

Figure 33.

Asleep,

1872

This gold medal winner at Naples demonstrated Edmonia’s technical mastery. Photo courtesy: San Jose Public Library.

Figure 34.

Poor Cupid,

carved 1876

This marble statue is probably much like Edmonia’s

Cupid Caught,

which won a certificate in 1872 at Naples. She sold it the next year in San Francisco. Photo courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Alfred T. Morris, Sr.

1776 to 1876

America had buzzed for years about the ripening plum of national pride, the long-awaited Centennial. Everyone agreed it had to top every other jubilee ever held. Congress debated for over a year before choosing Philadelphia. The official commission finally met in 1872. Its official seal quoted an Old Testament phrase, the one inscribed on the Liberty Bell: “Proclaim Liberty throughout the land, unto all inhabitants thereof.”

[468]

Used as an exhortation by Sojourner Truth decades earlier, the choice had thrilled foes of slavery. Now Reconstruction aimed to put it into practice. Many southern legislatures passed laws to give colored people full and equal access to transit, trade and entertainment. Senator Sumner pressed a Federal Civil Rights Bill in Congress. By year’s end, the nation reelected president U. S. Grant in a landslide victory.

In hindsight, we see Edmonia living in a social twilight in Rome, returning to America periodically to renew her spirit as she joined the fray. She must have dreamed of a sunny public showing in Philadelphia. The home of the phrase “all men are created equal” could not have been more appropriate for a celebration of Emancipation. There her statues could openly rival the greatest art of her generation in full view of critics, judges, and the public – colored and white.

America was the place for a showdown. It was where the viral “imputation of incapacity” (as Tuckerman’s critic called it) poisoned talent, education, and opportunity. Art was her weapon. When she toured, the old anti-slavery crowd took heart. Colored people understood her gifts, took pride, and found new possibilities for themselves. An uncertain white mainstream, open to influence, also came. The Centennial promised to bring more viewers than any other show she could imagine.

In the harsh light of day, she must have realized it would be her most challenging task. America was where the worst bigots railed and schemed against people of color. They would arrive at Philadelphia in packs and gangs, starving for signs of a break from intrusions on their way of life. How would they explain her celebrity, her entry, and her mastery of fine art?

She would later shudder to find they were running the show.

Happy dreams dissolved into an urgent need to create something large, new, and exceptional – a showpiece that would anchor her other entries. While most artists would send something already carved but for some reason not sold, she borrowed money for a block of stone large enough to express the growth of her ambition. She had gambled in the past and had done well – but not without pressing her limits.

She must have turned over a host of ideas. What about a colossal memorial to one of her established heroes – Longfellow, Lincoln, Sumner, Brown, or Shaw? Why not Columbus, George Washington, or Ben Franklin – all safely in keeping with the American theme? Why not more prize-winning

putti?

Why not one of the native champions suggested by the Tuckerman book, or a new Hiawatha scene? Pocahontas, contemplated years before, could have been a distinct possibility. Why not the Holy Virgin, held so dear? Why not revisit Emancipation with a larger, more buoyant

Forever Free

or a fourth, more stunning “freed woman?”

For reasons that seem obvious today, she must have scratched one after another. As Charlotte Cushman had pointed out, only a deprived minority and a few old reformers took interest in abolition anymore. The surviving soreness with Mrs. Child and her clique must have blocked further thoughts in that direction. Tuckerman’s writer had sneered at her most popular works, the Hiawatha groups. Most Protestants, the American majority, would recoil from a Madonna or any other Catholic icon.

Putti

were adorable and popular – too much so. They were not likely to command the attention of serious critics, all male, in America.

She needed to move on. She needed a well-known

literary

subject that would stir the common man while causing a buzz among literate critics.

Just doors away from her studio, W. W. Story and his grand “museum” reigned over the district, drawing lookers and art buyers from all over the world. As the premier American artist in Rome, he cast a longer shadow than any other artist did. He held the attention of the celebrities, elegant and clever, that shared dinners and exchanged letters with him.

Elevated in his own mind by family wealth, Brahmin breeding, and the company of famous writers, he considered himself more poet than stone carver. He rarely acknowledged his artist neighbors. He sneered at those who earned an honest living, certainly at all women sculptors save the effervescent Hosmer, whose social skills set her apart.

Local artists (and many others) did not share his opinions. They saw nothing deep in his conception, nothing sharp about his eye, nothing special in his mastery of materials. Nothing, in fact, pleased them more than gossip about him rudely demanding that Hiram Powers, or was it Thomas Ball? – or both? – loan him a bust of Edward Everett for use as a model. Such loans were common courtesy among colleagues, to be had for the asking. Such lore of Story the boor hardened their estrangement. They considered him a snob.

[469]

In Boston as well, his standing faltered as people studied his large bronze

Everett

in the Public Garden. Letters in the

Boston Evening Transcript

offered nothing but ridicule. The

Atlantic Monthly

denounced the pose. The chagrined author, according to the

New York Times,

pushed his plaster model into a dark corner. Under constant fire, the bronze moved repeatedly, stored for a while in a wood yard and lately miles away in Dorchester.

Rumor had it that Story would grace the Centennial with his African images,

Cleopatra

and the

Libyan Sibyl.

The American public would see these works for the first time. They had received word of his

Cleopatra

with excitement in 1862, when it appeared in London. Two copies soon came to America in the hands of private collectors. Neither went on public display until 1882, when one appeared at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

For the most part, Americans loved the marble

Cleopatra

long-distance. But was it Story’s statue they loved, or was it Hawthorne’s? Hawthorne was the cause of its glory; Hawthorne’s novel,

The Marble Faun,

the conduit. Before inventing his popular fiction with pen and ink, Hawthorne had witnessed Story’s work, unfinished, in clay.

[470]

By saluting Story in his preface, Hawthorne set the stage for Story’s entry in the London show with spellbinding praise in the chapters that followed. Admiring fans overlooked the line between fact and fiction (to this day!). Mesmerized, they came to the Story studio with Hawthorne’s book in hand to read aloud in fawning reverence to the relentless passages, quoted fully here to convey their sense of awe and hypnotic power.

[471]

He drew away the cloth that had served to keep the moisture of the clay model from being exhaled. The sitting figure of a woman was seen. She was draped from head to foot in a costume minutely and scrupulously studied from that of ancient Egypt, as revealed by the strange sculpture of that country, its coins, drawings, painted mummy-cases, and whatever other tokens have been dug out of its pyramids, graves, and catacombs. Even the stiff Egyptian head-dress was adhered to, but had been softened into a rich feminine adornment, without losing a particle of its truth. Difficulties that might well have seemed insurmountable had been courageously encountered and made flexible to purposes of grace and dignity; so that Cleopatra sat attired in a garb proper to her historic and queenly state, as a daughter of the Ptolomeys, and yet such as the beautiful woman would have put on as best adapted to heighten the magnificence of her charms, and kindle a tropic fire in the cold eyes of Octavius.

A marvelous repose – that rare merit in statuary, except it be the lumpish repose native to the block of stone – was diffused throughout the figure. The spectator felt that Cleopatra had sunk down out of the fever and turmoil of her life, and for one instant – as it were, between two pulse throbs – had relinquished all activity, and was resting throughout every vein and muscle. It was the repose of despair, indeed; for Octavius had seen her, and remained insensible to her enchantments. But still there was a great smouldering furnace deep down in the woman’s heart. The repose, no doubt, was as complete as if she were never to stir hand or foot again; and yet, such was the creature's latent energy and fierceness, she might spring upon you like a tigress, and stop the very breath that you were now drawing midway in your throat.

The face was a miraculous success. The sculptor had not shunned to give the full Nubian lips, and other characteristics of the Egyptian physiognomy. His courage and integrity had been abundantly rewarded; for Cleopatra's beauty shone out richer, warmer, more triumphantly beyond comparison than if, shrinking timidly from the truth, he had chosen the tame Grecian type. The expression was of profound, gloomy, heavily revolving thought; a glance into her past life and present emergencies, while her spirit gathered itself up for some new struggle, or was getting sternly reconciled to impending doom. In one view, there was a certain softness and tenderness, – how breathed into the statue, among so many strong and passionate elements, it is impossible to say. Catching another glimpse, you beheld her as implacable as a stone and cruel as fire.

In a word, all Cleopatra – fierce, voluptuous, passionate, tender, wicked, terrible, and full of poisonous and rapturous enchantment – was kneaded into what, only a week or two before, had been a lump of wet clay from the Tiber. Soon, apotheosized in an indestructible material, she would be one of the images that men keep forever, finding a heat in them which does not cool down, throughout the centuries?

[472]

Not done, Hawthorne persisted in a later chapter, to reach some sort of final cadence:

Kenyon's Roman artisans, all this while, had been at work on the Cleopatra. The fierce Egyptian queen had now struggled almost out of the imprisoning stone; or, rather, the workmen had found her within the mass of marble, imprisoned there by magic, but still fervid to the touch with fiery life, the fossil woman of an age that produced statelier, stronger, and more passionate creatures than our own. You already felt her compressed heat, and were aware of a tiger-like character even in her repose. If Octavius should make his appearance, though the marble still held her within its embrace, it was evident that she would tear herself forth in a twinkling, either to spring enraged at his throat, or, sinking into his arms, to make one more proof of her rich blandishments, or, falling lowly at his feet, to try the efficacy of a woman's tears.

[473]