The Long Tail (2 page)

Authors: Chris Anderson

I was, needless to say, way, way off. The answer was 98 percent.

“It’s amazing, isn’t it?” Vann-Adibé said. “Everyone gets that wrong.” Even he had been stunned: As the company added more titles to its collections, far beyond the inventory of most record stores and

into the world of niches and subcultures, they continued to sell. And the more the company added, the more they sold. The demand for music beyond the hits seemed to be limitless. True, the songs didn’t sell in big numbers, but nearly all of them sold something. And because these were just bits in a database that cost nearly nothing to store and deliver, all those onesies and twosies started to add up.

What Vann-Adibé had discovered was that the aggregate market for niche music was huge, and effectively unbounded. He called this the “98 Percent Rule.” As he later put it to me, “In a world of almost zero packaging cost and instant access to almost all content in this format, consumers exhibit consistent behavior: They look at almost everything. I believe that this requires major changes by the content producers—I’m just not sure what changes!”

I set out to answer that question. I realized that his counterintuitive statistic contained a powerful truth about the new economics of entertainment in the digital age. With unlimited supply, our assumptions about the relative roles of hits and niches were all wrong. Scarcity requires hits—if there are only a few slots on the shelves or the airwaves, it’s only sensible to fill them with the titles that will sell best. And if that’s all that’s available, that’s all people will buy.

But what if there are infinite slots? Maybe hits are the wrong way to look at the business. There are, after all, a lot more non-hits than hits, and now both are equally available. What if the non-hits—from healthy niche product to outright misses—all together added up to a market as big as, if not bigger than, the hits themselves? The answer to that was clear: It would radically transform some of the largest markets in the world.

And so I embarked on a research project that was to take me to all the leaders in the emerging digital entertainment industry, from Amazon to iTunes. Everywhere I went the story was the same: Hits are great, but niches are emerging as the big new market. The 98 Percent Rule turned out to be nearly universal. Apple said that every one of the then 1 million tracks in iTunes had sold at least once (now its inventory is twice that). Netflix reckoned that 95 percent of its 25,000 DVDs (that’s now 90,000) rented at least once a quarter. Amazon didn’t give out an exact number, but independent academic research

on its book sales suggested that 98 percent of its top 100,000 books sold at least once a quarter, too. And so it went, from company to company.

Each company was impressed by the demand they were seeing in categories that had been previously dismissed as beneath the economic fringe, from the British television series DVDs that are proving surprisingly popular at Netflix to the back-catalog music that’s big on iTunes. I realized that, for the first time, I was looking at the true shape of demand in our culture, unfiltered by the economics of scarcity.

That shape is, to be clear, really, really weird. To think that basically everything you put out there finds demand is just odd. The reason it’s odd is that we don’t typically think in terms of one unit per quarter. When we think about traditional retail, we think about what’s going to sell a lot. You’re not much interested in the occasional sale, because in traditional retail a CD that sells only one unit a quarter consumes exactly the same half-inch of shelf space as a CD that sells 1,000 units a quarter. There’s a value to that space—rent, overhead, staffing costs, etc.—that has to be paid back by a certain number of inventory turns per month. In other words, the onesies and twosies waste space.

However, when that space doesn’t cost anything, suddenly you can look at those infrequent sellers again, and they begin to have value. This was the insight that led to Amazon, Netflix, and all the other companies I was talking to. All of them realized that where the economics of traditional retail ran out of steam, the economics of online retail kept going. The onesies and twosies were still only selling in small numbers, but there were so, so

many

of them that in aggregate they added up to a big business.

Throughout the first half of 2004 I fleshed out this research in speeches, the thesis advancing with each talk. Originally the speech was called “The 98 Percent Rule.” Then it was “New Rules for the New Entertainment Economy” (not one of my better naming moments).

But by then I had some hard data, thanks to Rhapsody, which is one of the online music companies. They had given me a month’s worth of customer usage data, and when I graphed it out, I realized that the curve was unlike anything I’d seen before.

It started like any other demand curve, ranked by popularity. A few

hits were downloaded a huge number of times at the head of the curve, and then it fell off steeply with less popular tracks. But the interesting thing was that it never fell to zero. I’d go to the 100,000th track, zoom in, and the downloads per month were still in the thousands. And the curve just kept going: 200,000, 300,000, 400,000 tracks—no store could ever carry this much music. Yet as far as I looked, there was still demand. Way out at the end of the curve, tracks were being downloaded just four or five times a month, but the curve still wasn’t at zero.

In statistics, curves like that are called “long-tailed distributions,” because the tail of the curve is very long relative to the head. So all I did was focus on the tail itself, turn it into a proper noun, and “The Long Tail” was born. It started life as slide 20 of one of my “New Rules” presentations. I think it was Reed Hastings, the CEO of Netflix, who convinced me that I was burying my lead. By the summer of 2004 “The Long Tail” was not just the title of my speeches; I was nearly finished with an article of the same name for my own magazine.

When “The Long Tail” was published in

Wired

in October 2004, it quickly became the most cited article the magazine had ever run. The three main observations—(1) the tail of available variety is far longer than we realize; (2) it’s now within reach economically; (3) all those niches, when aggregated, can make up a significant market—seemed indisputable, especially backed up with heretofore unseen data.

TAILS EVERYWHERE

One of the most encouraging aspects of the overwhelming response to the original article was the breadth of industries in which it resonated. The article originated as an analysis of the new economics of the entertainment and media industries, and I only expanded it a bit to mention in passing that companies such as eBay (with used goods) and Google (with small advertisers) were also Long Tail businesses. Readers, however, saw the Long Tail everywhere, from politics to public relations, and from sheet music to college sports.

What people intuitively grasped was that new efficiencies in distri

bution, manufacturing, and marketing were changing the definition of what was commercially viable across the board. The best way to describe these forces is that they are turning unprofitable customers, products, and markets into profitable ones. Although this phenomenon is most obvious in entertainment and media, it’s an easy leap to eBay to see it at work more broadly, from cars to crafts.

Seen broadly, it’s clear that the story of the Long Tail is really about the economics of abundance—what happens when the bottlenecks that stand between supply and demand in our culture start to disappear and everything becomes available to everyone.

People often ask me to name some product category that does not lend itself to Long Tail economics. My usual answer is that it would be in some undifferentiated commodity, where variety is not only absent but unwanted. Like, for instance, flour, which I remembered being sold in the supermarket in a big bag labeled “Flour.” Then I happened to step inside our local Whole Foods grocery and realized how wrong I was: Today the grocery carries more than twenty different types of flour, ranging from such basics as whole wheat and organic varieties to exotics such as amaranth and blue cornmeal. There is, amazingly enough, already a Long Tail in flour.

Our growing affluence has allowed us to shift from being bargain shoppers buying branded (or even unbranded) commodities to becoming mini-connoisseurs, flexing our taste with a thousand little indulgences that set us apart from others. We now engage in a host of new consumer behaviors that are described with intentionally oxymoronic terms: “massclusivity,” “slivercasting,” “mass customization.” They all point in the same direction: more Long Tails.

A PREVIEW OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY ECONOMICS

This book is partly an economic research project, with the help and involvement of students and professors from the Stanford, MIT, and Harvard business schools. It’s partly the fruit of more than a hundred speeches, brainstorming sessions, and site visits with companies and industry groups that see the Long Tail changing their world. And it’s

partly a collaboration with the dozens of companies and executives who shared many megabytes of internal data, giving me an unprecedented view on the emerging micro-economics of markets in the online age.

What’s fascinating about this moment is that the economics of the twenty-first century are already evident in outline form in the databases of the Googles, Amazons, Netflixes, and iTunes of the world. In those many terabytes of user behavior data is a clue to how consumers will behave in markets of infinite choice, a question that hadn’t been meaningful until recently but has now become essential to understand.

Surprisingly, very few economists are looking at this data, mostly because they haven’t asked (most of the academics I worked with are in business schools, only a few of them are economists). There are some exceptions—University of California Berkeley economist Hal Varian works part-time at Google, and auction-theory economists unsurprisingly love eBay—but they’re rare. Some of the data in this book has never before seen the light of day.

Given the uncharted waters, I solicited a lot of help from experts in all corners. As an experiment, I worked through many of the trickier conceptual and articulation issues in public, on my blog at thelongtail.com. The usual process would go like this: I’d post a half-baked effort at explaining how the 80/20 Rule is changing, for instance, and then dozens of smart readers would write comments, emails, or their own blog posts to suggest ways to improve it. Somehow this wonky public brainstorming managed to attract an average of more than 5,000 readers a day.

In software, developers release early (“beta”) versions of their code to their most avid users. In exchange for the privileged early look at the program, these users test it on their own machines, in their own way, and find errors that the developer missed. Such beta-testing is essential to creating robust software applications. My hope is that the same process—stress-testing many of my ideas in public—has led to a better, or at least sounder, book.

I should note here the difference between beta-testing ideas in public and actually writing a book in public. Although many have tried

to do the latter—posting draft chapters online and sometimes even opening the text to collective editing—I chose to use the blog mostly as a public diary of my research in progress. The actual writing of the book, and most of the words in the following pages, I did offline.

Finally, one more note on parentage. Although I coined the term “The Long Tail,” I can’t claim any credit for creating the concept of using the efficient economics of online retail to aggregate a large inventory of relatively low sellers. That would be Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, circa 1994. Most of what I’ve learned has come from talking to him, his counterparts at Netflix and Rhapsody, and others who have all been acting on this for years.

Those entrepreneurs are the real inventors here. What I’ve tried to do is synthesize the results into a framework. That is, of course, what economics does: It seeks to find neat, easily understood frameworks that describe real-world phenomena. Coming up with the framework is an advance in itself, but it pales next to the original inventions of all those who discovered and acted on the phenomena in the first place.

HOW TECHNOLOGY IS TURNING MASS MARKETS INTO MILLIONS OF NICHES

In 1988, a

British mountain climber named Joe Simpson wrote a book called

Touching the Void

, a harrowing account of near death in the Peruvian Andes. Though reviews for the book were good, it was only a modest success, and soon was largely forgotten. Then, a decade later, a strange thing happened. Jon Krakauer’s

Into Thin Air,

another book about a mountain-climbing tragedy, became a publishing sensation. Suddenly,

Touching the Void

started to sell again.

Booksellers began promoting it next to their

Into Thin Air

displays, and sales continued to rise. In early 2004, IFC Films released a docudrama of the story, to good reviews. Shortly thereafter, HarperCollins released a revised paperback, which spent fourteen weeks on the

New York Times

best-seller list. By mid-2004,

Touching the Void

was outselling

Into Thin Air

more than two to one.

What happened? Online word of mouth. When

Into Thin Air

first came out, a few readers wrote reviews on Amazon.com that pointed out the similarities with the then lesser-known

Touching the Void,

which they praised effusively. Other shoppers read those reviews, checked out the older book, and added it to their shopping carts. Pretty soon the online bookseller’s software noted the patterns in buying

behavior—“Readers who bought

Into Thin Air

also bought

Touching the Void

”—and started recommending the two as a pair. People took the suggestion, agreed wholeheartedly, wrote more rhapsodic reviews. More sales, more algorithm-fueled recommendations—and a powerful positive feedback loop kicked in.

Particularly notable is that when Krakauer’s book hit shelves, Simpson’s was nearly out of print. A decade ago readers of Krakauer would never even have learned about Simpson’s book—and if they had, they wouldn’t have been able to find it. Online booksellers changed that. By combining infinite shelf space with real-time information about buying trends and public opinion, they created the entire

Touching the Void

phenomenon. The result: rising demand for an obscure book.

This is not just a virtue of online booksellers; it is an example of an entirely new economic model for the media and entertainment industries, one just beginning to show its power. Unlimited selection is revealing truths about

what

consumers want and

how

they want to get it in service after service—from DVDs at the rental-by-mail firm Netflix to songs in the iTunes Music Store and Rhapsody. People are going deep into the catalog, down the long, long list of available titles, far past what’s available at Blockbuster Video and Tower Records. And the more they find, the more they like. As they wander farther from the beaten path, they discover their taste is not as mainstream as they thought (or as they had been led to believe by marketing, a hit-centric culture, and simply a lack of alternatives).

The sales data and trends from these services and others like them show that the emerging digital entertainment economy is going to be radically different from today’s mass market. If the twentieth-century entertainment industry was about

hits

, the twenty-first will be equally about

niches

.

For too long we’ve been suffering the tyranny of lowest-common-denominator fare, subjected to brain-dead summer blockbusters and manufactured pop. Why? Economics. Many of our assumptions about popular taste are actually artifacts of poor supply-and-demand matching—a market response to inefficient distribution.

The main problem, if that’s the word, is that we live in the physical

world, and until recently, most of our entertainment media did, too. That world puts dramatic limitations on our entertainment.

THE TYRANNY OF LOCALITY

The curse of traditional retail is the need to find local audiences. An average movie theater will not show a film unless it can attract at least 1,500 people over a two-week run. That’s essentially the rent for a screen. An average record store needs to sell at least four copies of a CD per year to make it worth carrying; that’s the rent for a half inch of shelf space. And so on, for DVD rental shops, video-game stores, booksellers, and newsstands.

In each case, retailers will carry only content that can generate sufficient demand to earn its keep. However, each can pull from only a limited local population—perhaps a ten-mile radius for a typical movie theater, less than that for music and bookstores, and even less (just a mile or two) for video rental shops. It’s not enough for a great documentary to have a potential national audience of half a million; what matters is how much of an audience it has in the northern part of Rockville, Maryland, or among the mall shoppers of Walnut Creek, California.

There is plenty of great entertainment with potentially large, even rapturous, national audiences that cannot clear the local retailer bar. For instance,

The Triplets of Belleville

, a critically acclaimed film that was nominated for the best animated feature Oscar in 2004, opened on just six screens nationwide. An even more striking example is the plight of Bollywood in America. Each year, India’s film industry produces more than eight hundred feature films. There are an estimated 1.7 million Indians living in the United States. Yet the top-rated Hindi-language film,

Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India

, opened on just two screens in the States. Moreover, it was one of only a handful of Indian films that managed to get

any

U.S. distribution at all that year. In the tyranny of geography, an audience spread too thinly is the same as no audience at all.

Another constraint of the physical world is physics itself. The radio

spectrum can carry only so many stations, and a coaxial cable only so many TV channels. And, of course, there are only twenty-four hours of programming a day. The curse of broadcast technologies is that they are profligate users of limited resources. The result is yet another instance of having to aggregate large audiences in one geographic area—another high bar above which only a fraction of potential content rises.

For the past century, entertainment has offered an easy solution to these constraints: a focus on releasing

hits

. After all, hits fill theaters, fly off shelves, and keep listeners and viewers from touching their dials and remotes. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that. Sociologists will tell you that hits are hardwired into human psychology—that they’re the effect of a combination of conformity and word of mouth. And certainly, a healthy share of hits do earn their place: Catchy songs, inspiring movies, and thought-provoking books can attract big, broad audiences.

However, most of us want more than just the hits. Everyone’s taste departs from the mainstream somewhere. The more we explore alternatives, the more we’re drawn to them. Unfortunately, in recent decades, such alternatives have been relegated to the fringes by pumped-up marketing vehicles built to order by industries that desperately needed them.

Hit-driven economics, which I’ll discuss in more depth in later chapters, is a creation of an age in which there just wasn’t enough room to carry everything for everybody: not enough shelf space for all the CDs, DVDs, and video games produced; not enough screens to show all the available movies; not enough channels to broadcast all the TV programs; not enough radio waves to play all the music created; and nowhere near enough hours in the day to squeeze everything through any of these slots.

This is the world of

scarcity

. Now, with online distribution and retail, we are entering a world of

abundance

. The differences are profound.

MARKETS WITHOUT END

For a better look at the world of abundance, let’s return to online music retailer Rhapsody. A subscription-based streaming service owned by RealNetworks, Rhapsody currently offers more than 4 million tracks.

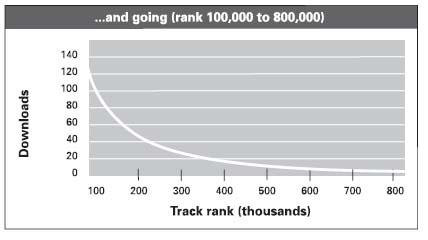

Chart Rhapsody’s monthly statistics and you get a demand curve that looks much like any record store’s: huge appeal for the top tracks, tailing off quickly for less popular ones. Below is a graph representing the top 25,000 tracks downloaded via Rhapsody in December 2005.

The first thing you might notice is that all the action appears to be in a tiny number of tracks on the left-hand side. No surprise there. Those are the hits. If you were running a music store and had a finite amount of space on your shelves, you’d naturally be looking for a cutoff point that’s not too far from that peak.

So although there are millions of tracks in the collective catalogs of all the labels, America’s largest music retailer, Wal-Mart, cuts off its

inventory pretty close to the Head. It carries about 4,500 unique CD titles. On Rhapsody, the top 4,500 albums account for the top 25,000 tracks, which is why I cut the chart off right there. What you’re looking at is Wal-Mart’s inventory, in which the top 200 albums account for more than 90 percent of the sales.

Focusing on the hits certainly seems to make sense. That’s the lion’s share of the market, after all. Anything after the top 5,000 or 10,000 tracks appears to rank pretty close to zero. Why bother with those losers at the bottom?

That, in a nutshell, is the way we’ve been looking at markets for the last century. Every retailer has its own economic threshold, but they all cut off what they carry somewhere. Things that are likely to sell in the necessary numbers get carried; things that aren’t, don’t. In our hit-driven culture, people get ahead by focusing obsessively on the left side of the curve and trying to guess what will make it there.

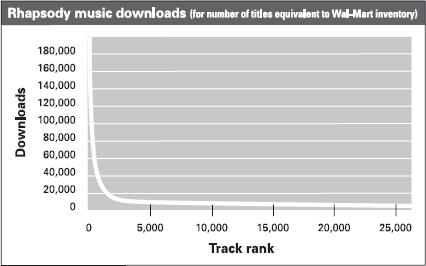

But let’s do something different for a change. After a century of staring at the left of this curve, let’s turn our heads to the right. It’s disorienting, I know. There appears to be nothing there, right? Wrong—look closer. Now closer. You’ll notice two things.

First, that line isn’t quite at zero. It just looks that way because the hits have compressed the vertical scale. To get a better view of the niches, let’s zoom in and look past the top sellers. This next chart continues the curve from the 25,000th track to the 100,000th. I’ve changed the vertical scale so the line isn’t lost in the horizontal axis. As you can see, we’re still talking about significant numbers of downloads. Down here in the weeds, where we’d always assumed there was essentially no meaningful demand, the songs are still being downloaded an average of 250 times a month. And because there are so many of these non-hits, their sales, while individually small, quickly add up. The area under the curve down here where the curve appears from a distance to bump along the bottom actually accounts for some 22 million downloads a month, nearly a quarter of Rhapsody’s total business.

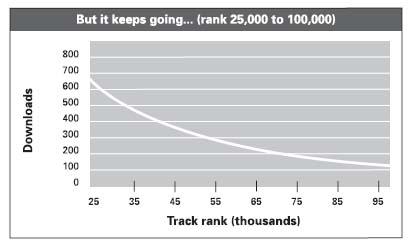

And it doesn’t stop there. Let’s zoom and pan again. This time it’s the far end of the Tail: rank 100,000 to 800,000, the land of songs that can’t be found in any but the most specialized record stores.