The Mapmaker's Wife (27 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

Gonzalo Pizarro and his men had not fared as well. Left behind in the forest, they were reduced to eating lizards and drinking the blood of their horses, which they cooked with herbs in their helmets. A band of eighty half-naked, emaciated, and slightly crazed men arrived back in Quito in August 1542, Pizarro seething with bitterness toward Orellana, whom he accused of treason. In the fate of the two groups, though, one could see a picture of two wildernesses. Along the foot of the Andes was a dense and forbidding jungle. But after passing through it, one came to the navigable waters of the Amazon, along which game and food could be found. Travel along this waterway, except for attacks from natives, was fairly easy.

Although Spaniards in Peru continued to dream of El Dorado, only a few dared to venture into the jungle after Pizarro’s failed adventure. The next expedition of any note was sent in 1560 by the viceroy of Peru, who did so partly as a way of getting rid of troublemakers in the colony. Three hundred men led by Pedro de Ursúa departed from Lima, heading into the jungle via the Huallaga River and with orders to find El Dorado and conquer the Omaguas. Ursúa brought along his mistress, which stirred up jealousy among his men, and on New Year’s Day 1561, Lope de Aguirre—one of history’s great psychopaths—led a mutiny, killing Ursúa and hatching a plot to return to Peru to conquer it. The route Aguirre took across the Amazon basin to reach the Atlantic is uncertain even today. Either he followed the Amazon to its end, or he turned up the Río Negro, crossed over into the Orinoco River, and followed that waterway north to the Caribbean. What is known is that on July 20, 1561, he seized the island of Margarita, slaughtering anyone who dared to stand in his way. He then launched an invasion of the mainland, where he was defeated by royalist troops and beheaded.

Aguirre’s was the last transcontinental journey through the Amazon basin for nearly eighty years. Heading east from the Andes, through the dense rain forest of the mountains, was so difficult that it seemed to bring ruin to those who tried. However, at the end of the sixteenth century, the Dutch, English, and French all established colonies at the mouth of the Amazon, kicking off European exploration of the Amazon from the eastern end. The Portuguese arrived in 1616, setting up a military fort named Belém do Pará. Although this was supposed to be Spanish land, at that time Spain and Portugal were united under one king, and so Spain, struggling to manage its colonies in Peru and Mexico, was only too happy to see the Portuguese take on the settlers from other countries. Over the next ten years, the Portuguese drove the French, Dutch, and English out of the Amazon, and they moved north to the swampy coasts of Guiana.

South of the Amazon, Portuguese settlers along the coast had

already carved out huge sugar plantations, and they now looked to the river as a source of slave labor. The Indians, in their words, were “red gold.” Although enslavement of the indigenous people was theoretically illegal, both Spanish and Portuguese law provided the settlers with loopholes to exploit. Settlers were allowed to make slaves out of “prisoners taken in just wars,” and a just war was in the eye of the beholder. They were also allowed to enslave Indians captured by other tribes. The rational for that provision was that the “freed” Indians became their indentured servants who had to work the plantations in order to “repay” the ransom. Once the Portuguese gained control of the river’s mouth, the slave trade exploded and the mass migration of Indians along the Amazon began. Some tribes, such as the Omaguas, moved further upriver to escape, and others fled into the interior.

As the slave traders conducted their hunting expeditions, they expanded Portugal’s control over the Amazon. Although Portugal and Spain may have shared a king, the two countries remained separate, and the Amazon—in the 1630s—was clearly up for grabs. Portugal was laying claim to the vast interior of the continent, which was why, in February 1637, Portuguese military commanders in Pará, on the southern shore of the delta, reacted with alarm when two Spanish Franciscan monks and five Spanish soldiers arrived in their port after having canoed

down

the river. Were the Spanish going to push forward territorial claims from the west?

The Franciscans had not made their voyage with any such intention. They had left Quito several years earlier in order to establish a mission on the Napo River, but hostile Indians had driven them off, and they had subsequently traveled several thousand miles to Pará. Even so, their visit stirred the Portuguese to mount a huge expedition, under the command of Captain Pedro Teixeira, to march up the river and formally stake Portugal’s claim to it. He led a force of seventy soldiers traveling in a fleet of forty-seven canoes, with 1,200 Indians and Negroes manning the oars, and even after he had reached the end of the navigable part of the Napo River, he and his soldiers continued on, arriving in Quito in October 1638. Their trip

had taken a year, and now it was Spain’s turn to be alarmed. The authorities in Quito ordered the Portuguese crew back to Pará but placed several Spaniards on board, including a Jesuit priest, Cristóbal de Acuña, who was told to produce a report on the river. It was the first time that Spain had sought to survey this vast region.

The party left Quito on February 16, 1639, and reached Pará ten months later. Along the way, Teixeira staked out an arbitrary boundary line between the two countries, using a carved log to mark the spot. He also drew up a formal “Act of Possession” to back Portugal’s legal claim to the lion’s share of the Amazon. Meanwhile, Acuña published an account of their voyage in which he sang of the river’s riches and recommended that Spain should occupy all of it. The Amazon, he marveled, had more people than the “Ganges, Tigris, or Nile.” Many of the natives were friendly, and he hailed the Omaguas as the

“most intelligent, the best governed on the river.” There were healing drugs to be found in the forest, huge trees that could be harvested for shipbuilding, and fertile riverbanks that could be used to grow manioc, sweet potatoes, pineapples, guavas, and coconuts. The river was swimming with fish, the woods were full of game—including tapirs, deer, peccaries, monkeys, and armadillos—and the lagoons were populated by numerous birds. His was a wilderness that was more bountiful paradise than fearsome jungle.

“Settlements are so close together that one is scarcely lost sight of before another comes into view,” he wrote. “It may be imagined how numerous are the Indians who support themselves from so plentiful a country.” Yet lower on the Amazon, closer to the mouth, he found a river undergoing a transformation, its banks emptied by the slave trade, “with no one [left] to cultivate the land.”

Acuña’s book was titled

New Discovery of the Great River of the Amazons

, and in many ways he provided a straightforward account of what he saw. However, he also gave credence to what he had heard along the way about strange people living inland from the Amazon. He wrote of lands inhabited by giants and dwarfs, and of

a race of people whose feet grew backward so that those hunting them would be led astray by their tracks. He confirmed that a tribe of warrior women inhabited this jungle, up north toward Guiana. These tales kept alive the picture of the Amazon as a wilderness that was both bountiful and magical, a world where explorers could indeed find great treasures.

Portugal now had little motivation to rein in its slave trade, which exploded in earnest. Entire tribes were “descended” down the river by slave traders, and the enslaved Indians died in great numbers from disease, despair, and malnutrition.

“They killed them as one kills mosquitoes,” protested a Jesuit priest, João Daniel. One after another the Indian tribes disappeared, falling like dominoes as one went upriver. One slave trader complained, in 1693, that it was necessary to travel two months from Pará to find any natives to capture.

Daniel and other Jesuits sought to protect Indians from the slave trade by building missions where they could come and live, and presumably find a safe refuge. However, the Portuguese stations were something of a double-edged sword, for the priests would convert the Indians to Christianity and often force them to adopt Christian ways, thereby destroying their culture and tribal identity. Meanwhile, Spain turned to the Jesuits and their missionary work with a political goal in mind: By encouraging the black-robed priests to build missions along the upper Amazon, Spain could hope to take possession of this region and thus prevent the Portuguese from grabbing an ever greater share of the Amazon. The boundary between the two countries would effectively be established by the mission stations rather than by any formal treaty between the two countries.

Spanish Jesuits erected their first such mission at Borja in 1658, at the foot of the Andes, where the Marañón River

*

pours through a nasty strait called the Pongo de Manseriche. A little while later, they established a second settlement further downstream at

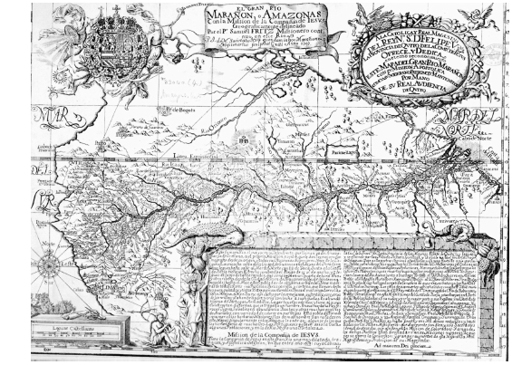

Lagunas, where the Huallaga flows into the Amazon. In 1681, representatives of the Omaguas traveled upriver to Lagunas to request that a missionary be sent to them—they needed protection from the Portuguese slave traders—and the priest who arrived five years later was a memorable, ruddy-faced German, Samuel Fritz. For the next thirty-seven years, he worked along the banks of the Amazon, tending to a “parish” that extended for more than 1,000 miles. During this time, he produced the first somewhat reliable map of the river.

Fritz’s mapmaking journey arose from what is possibly the longest trip ever made in search of medical help. In 1689, he was struck by malaria and for days lay dying in a flooded Yurimagua village. Everyone had fled to higher ground except for a lone boy, who tried to comfort him. Fritz was so weak that lizards and rats ran across his body, and at night his sleep was disturbed by the

malevolent grunting of crocodiles outside his hut. At last, he gathered enough strength to get into a canoe and head downriver for help. Once in motion, he stayed in motion, and he traveled more than 2,000 miles to Pará, where the Portuguese promptly arrested him, reasoning that he was a spy. After eighteen months in prison, he was freed by an order from Portugal’s King Pedro II. On his return upriver, with the aid of a few crude instruments, he was able to roughly chart the Amazon. He traveled all the way to Lima, and it was this map, along with Cristóbal de Acuña’s book, that inspired La Condamine to take this route home.

Samuel Fritz’s Map of the Amazon, 1707.

By permission of the British Library

.

F

ROM THE BEGINNING

of the French expedition, there had been some talk that the group, as a whole, would return via the Amazon. But as the mission went on and on and the group came to be rent by dissension, that idea faded away. However, La Condamine never lost interest in the route, and as early as 1738, he had initiated the process of obtaining a passport from the Portuguese.

“As for the discomforts,” he wrote in his journal in 1741, “I knew these would be great, and everything which I had heard only served to increase the wish I had to experience it for myself.”

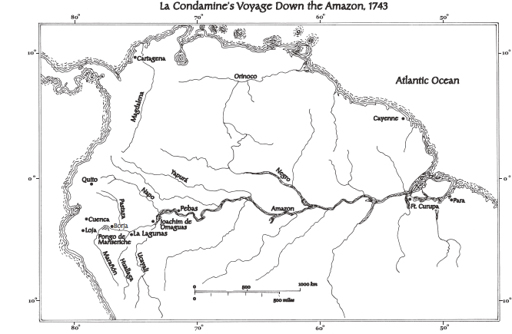

At the last minute, La Condamine also coaxed Pedro Maldonado to join him. Maldonado, who had finished his Esmeraldas road by 1742, had initially begged off, his family urging him not to go on such a dangerous venture. By the time Maldonado made up his mind to ignore his family’s advice, it was too late for him to leave with La Condamine, so they decided to take different routes to the river and meet up in Lagunas. Maldonado, leaving from the Riobamba area, would skirt around the base of Mount Tungurahua and head east on foot down a steep gorge that spilled out of the Andes; then he would follow the Bobonaza and Pastaza Rivers to the Amazon. La Condamine, who would be departing from Tarqui after finishing his celestial observations, decided to head south to Jaen, where, after a short journey overland, he could pick up the

Marañón. This would allow him to draw a map of the entire navigable part of the Amazon and would also enable him to see whether

“the famous strait known under the name of Pongo de Manseriche was as terrible up close at it had been described to me from afar.” In Quito, he noted, they spoke of this passage “only in hushed tones of admiration and fear.”