The Mapmaker's Wife (24 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

La Condamine’s blueprint for pyramids marking the Yaruqui baseline.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine

, Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi à l’équateur

(1751)

.

From La Condamine’s point of view, this was exceedingly generous. None of the French helpers—Verguin, Morainville, or Jean Godin—was going to see his name on the marble tablet. But Ulloa and Juan had grown up in a society where swords could be drawn over the use of

usted

, and they perceived the wording as an unforgivable slight. They informed La Condamine that the inscription should describe them as Spanish academicians—they wanted equal status. Replied La Condamine:

“Only the French members of the Academy were charged with this mission [and] we have always remained the masters of our work.” To describe Ulloa and Juan as academicians, he wrote, would be to award them “qualities which they did not possess.” One bemused observer of this squabble—Isabel’s uncle, the Marqués de Valleumbroso—deemed it worthy of

“a new comedy by Molière.” But this was colonial Spain, and the

argument blew up into a legal contest that clogged the Quito court with hundreds of documents, with the Creoles in the city cheering on La Condamine, for they rather enjoyed seeing two Spaniards humiliated.

The expedition, however, was clearly sputtering as the academicians tried to bring it to a close. The zenith sectors were in the repair shop. Louis Godin’s relationship with La Condamine and Bouguer remained so strained that more often than not they communicated with each other by letter. Senièrgues and Couplet were dead, and yet another member, Jussieu, was in bed with a raging fever, so sick that he had

“put his affairs and his conscience in order.” As a group, the expedition was falling apart, and then, late in 1740, the Peruvian viceroy called Ulloa and Juan to Lima. A British armada was sailing around Cape Horn with plans to attack Peruvian ports, and he wanted the two Spaniards to help prepare the colony’s defense. The expedition, at least for the moment, had come to a halt.

*

E

VEN MORE THAN THE OTHER ASSISTANTS

, Jean Godin was left at loose ends by this scattering of the expedition members. The others still had tasks to do. Hugo was working on the instruments, Morainville was building the pyramids, and Verguin was assisting La Condamine with his drawing of maps. But Jean’s job

had been to act as a signal carrier during the triangulation work, and now there was little for him to do. Nor was there money left for the expedition as a whole. His cousin Louis was descending ever deeper into debt, while La Condamine was relying on his personal funds to pay for his expenses and for the construction of the pyramids. In order to earn some money, Jean decided to travel to Cartagena, planning to trade in textiles. Before he left, however, La Condamine gave him a trunk filled with “natural curiosities” to take to the port, where he could arrange for its shipment to France. This request picked up Jean’s spirits, for it made him feel connected, in some small way, to the others.

He departed from Quito on October 3, 1740. It was 900 miles to Cartagena, along a tortuous route that could take three months to travel. The first 500 miles involved a trek by mule across the dry plains north of the city and then along the spine of the Andes. The most treacherous segment in the mountains was Guanacas Pass,

“the most famous in all South America” for its perils, Bouguer later wrote. The peaks in this region near Popayán were covered with snow, and so many mules had perished while crossing the pass that their bones covered the trail, making it impossible “to set a foot down without treading on them.” This route, Bouguer concluded, was “never hazarded without the utmost dread.”

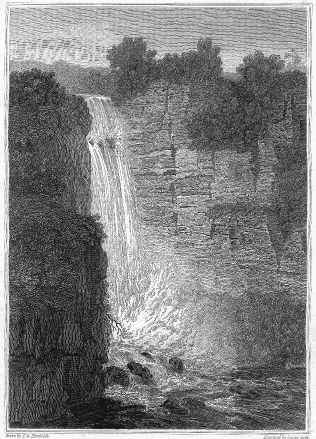

Jean Godin found it slow going; at times he was able to cover only three or four miles a day. It took him until the middle of November to make his way through the mountains and to reach the Magdalena River, where he was able to trade his mule for a canoe. This was a much more comfortable form of transport. Near Bogotá, he even took a short detour to Tequendama Falls, a waterfall “200 toises” in height that, at the time, was thought to be the tallest in the world.

When Jean arrived in Cartagena, the city was busily preparing for an attack by the British. Jean found some textiles to buy, and handed off La Condamine’s trunk to the captain of a French frigate. It contained a number of archaeological items certain to intrigue the Europeans: fossil axes, rock samples, petrified wood,

the skin of a small crocodile, a stuffed coral snake, several Incan artifacts, and antique clay vases that were shaped with such skill that the water whistled when poured. Unfortunately, the ship did not sail right away and was still docked in Cartagena on March 15, 1741, when the British launched their assault. They set fire to ships in the bay, including the frigate loaded with La Condamine’s trunk of curiosities, and all of the items were lost.

Tequendama Falls.

From John Pinkerton, ed

., A General Collection of the Best and Most Interesting Voyages and Travels in All Parts of the World,

vol. 14 (London, 1813)

.

Godin’s journey to and from Cartagena took more than six months, and as had so often been the case during his time in South America, he had traveled alone. He had grown quite accustomed to this difficult life. His trek to Cartagena, he wrote, reminded him of the years he had spent

“reconnoitering the ground for the meridian

of Quito, fixing signals on the loftiest mountains.” But back in Quito, he was once more at loose ends. As La Condamine said,

“His duties regarding the objective of our mission had ceased.” He was adrift in a Spanish colony far from his home, and it was then, over the next several months, that he became engaged to thirteen-year-old Isabel Gramesón.

There is no record of their courtship, either in Jean’s writings or La Condamine’s. The match, however, could only have been made with Pedro Gramesón’s approval, and in that regard, it was surprising. While he may have welcomed the French visitors into his home and delighted in their tales, he almost certainly would not have considered Jean Godin a good husband for his daughter. It was true that the two families shared common friends, the Pelletiers from Lignieres—alliances often lay behind arranged marriages. And Jean, during his years of service to the expedition, had proven himself to be a person of industry. But he was not Spanish and was planning to return to France, and it would hardly make sense for Pedro Gramesón to invest Isabel’s dowry in such a suitor.

His daughter, however, was strong-willed, and this was a union that would fulfill many of her wishes. She had often stated her desire to go to France. As Jean later wrote, she was “exceedingly solicitous” of traveling there. Hers was a childhood dream woven from many strands: Her grandfather on her father’s side was French, her father had entertained these famous visitors in his home, and all of Quito had gossiped about the wonders of Paris when the expedition had first come to the city. Women there, or so she had been told, presided over salons, attended the theater in fancy gowns, and danced the minuet at elegant balls. Marrying Jean promised to make all of that a reality, and at last Isabel’s father consented: He would provide the couple with a dowry that consisted of jewelry, textiles, 7,783 pesos in silver, and two slaves.

Jean and Isabel were married by Father Domingo Terol on December 29, 1741, in the Dominican College of San Fernando in Quito. La Condamine, Verguin, and Jussieu—who had recovered

from his fever—all attended, as did many of the elite in Quito and other rich Creoles from miles around. The large crowd was a reflection of the Gramesóns’ prominence, particularly on Isabel’s mother’s side. It is likely that Louis Godin, Bouguer, and Morainville also attended, bringing together all the French members of the expedition one final time.

The marriage ceremony was followed by a grand feast and dance. The guests sipped on liquors chilled by ice chipped from Mount Pichincha, drank grape brandy, and ate to their hearts’ content. Great plates of fish, fowl, and meats were served, and the dining tables were loaded with bowls of succulent fruits—chirimoyas, avocados, guavas, pomegranates, and strawberries. After the food was put away, everyone danced the fandango, the rhythm tapped out with a tambourine and castanets. More than one guest had brought a guitar, and according to one account, the Gramesóns had shipped in a clavichord from Guayaquil for the occasion. Isabel’s parents had spared no expense, and everyone could see how happy Isabel and Jean looked. Theirs, it seemed, was a marriage certain to bring good fortune to both.

After the wedding, Isabel went into seclusion for a month. In a society in which the cult of the Virgin Mary held sway, it was considered improper for a woman to be seen during the time of her “deflowering.” Once the thirty days had gone by, she and Jean began a round of visits to family and friends, a ritual signaling that she had passed into adulthood. Although it was expected that Isabel, in the future, would rarely venture out alone—social protocol required that she have a maid or her husband with her—she no longer needed to be to be hidden. She was fourteen years old and he was twenty-eight, a match that seemed right and proper to all, and even as they made their social rounds, she was already pregnant with their first child.

During this period, La Condamine, Bouguer, and Louis Godin repeated their celestial observations, but without success. Hugo’s repairs to the zenith sectors did not make any difference. A star’s zenith position would vary from five to twenty seconds from

night to night. They now had to confront a painful possibility: Perhaps they were trying to do the impossible. Perhaps they could not measure a degree of latitude with sufficient precision to definitively answer the question of the earth’s shape. They were sure that Maupertuis’s measurements in Lapland were not as accurate as theirs already were, and yet they knew that if they went ahead and used these imprecise celestial observations to calculate the length of a degree of latitude at the equator, some doubt would remain.

There were any number of factors that might be causing the variation. Perhaps, they speculated, atmospheric refraction was not constant. Perhaps its strength varied from night to night. Or perhaps the adobe walls of their observatories contracted or expanded ever so slightly in response to changes in temperature and humidity, which in turn caused a slight movement in the wire strung up to align the zenith sector along the meridian plane. Or could the star’s position actually be changing? Maybe, in their effort to make measurements more precise than anyone had ever made before, they had discovered something new about the universe: A star’s movement through the heavens might not be quite as fixed as previously believed. Perhaps a star could

wobble

. They mulled over all these possibilities and then, in late 1741, Bouguer wrote La Condamine with “devastating” news. He had concluded that the problems with their two zenith sectors had never been resolved. Hugo would have to make additional improvements to one of the sectors and build a second one anew. Sighed La Condamine:

“At a time when I was flattering myself that all of the obstacles that had been holding us back for so long were going to be removed and that I could finally set off en route back to France, I found myself forced to begin the work again. Although it was painful, it was clear to me that our work was not nearly done.”

As frustrating as this all was, the problems with the zenith sectors enabled La Condamine and Bouguer to pursue other investigations, which turned out to be very fruitful. La Condamine took

advantage of the hiatus to travel with Pedro Maldonado along his newly opened road to Esmeraldas. In 1736, La Condamine had stumbled through the rain forest along this route, but now the journey could be fairly easily made. This was progress, and once La Condamine was back in Esmeraldas, he happily renewed his study of a thick, white liquid called caoutchouc, which Indians took from the hevea tree. On his first visit to Esmeraldas, he had noticed that local Indians poured caoutchouc between shaped plantain leaves, let it harden, and then used it

“for the same purpose we use waxcloth.” La Condamine fashioned a waterproof pouch for his scientific instruments from this amazing material, sent back samples of it to France, and, in collaboration with Maldonado, wrote a monograph on its properties, helping to introduce rubber to Europe. La Condamine also came upon an Indian tribe that used a curious white metal to make jewelry, and when metallurgists in France received a sample of it from him, they immediately saw that this “platinum” was going to be very useful. La Condamine was in his element again, mining the New World for plants and minerals—

quinquina

, rubber, platinum—that would, in the years ahead, lead to important advances in medicine and industry.

He and the others chalked up numerous achievements during this time. After his trip to Esmeraldas, La Condamine collaborated with Verguin and Maldonado to produce a map of the Quito Audiencia that was far more accurate than any that had been drawn before. With Bouguer, he continued conducting experiments on the speed of sound and on the expansion and contraction of materials in response to temperature changes. The two observed solar and lunar eclipses, calculated the “obliquity of the ecliptic”—the tilt of the earth toward the sun—and investigated the strength of the magnetic attraction to both poles.

“It matters not on what place of the earth we stand,” Bouguer concluded, “we shall always feel the action of one pole as powerfully as the other.” Perhaps most important of all, La Condamine came up with the idea of using the “length of a seconds pendulum at the equator, at the altitude of

Quito” as a “natural measurement.” This would be a ruler defined by the gravitational pull of the earth rather than something arbitrary like a king’s foot, and it could provide a standardized measurement for all nations.

“One wishes that it would be universal,” La Condamine wrote, giving voice to a sentiment that, fifty years later, would inspire France to invent the meter.

*