The Mapmaker's Wife (21 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

*

Their initial triangle would be formed by Pichincha and the two ends of their baseline. Once they determined the interior angles of this triangle, they could—since they already knew the length of the baseline—calculate the lengths of the triangle’s other two sides.

*

The peak they were on is known today as Rucu Pichincha (15,413 feet). The volcano’s rim, Guagua Pichincha (15,728 feet), is a mile away. Neither Rucu Pichincha nor Guagua Pichincha is regularly snow-covered today, evidence of the changing climate in Ecuador. Pichincha remains an active volcano; it erupted in 1999, sending ash down on Quito.

*

While the French academicians were not the first to climb Pichincha, theirs was indeed the first recorded ascent of Corazon.

C

UENCA WAS NEARLY THE SAME SIZE

as Riobamba and had an equally pleasant climate, which made it seem an ideal place to rest. Both groups—La Condamine’s and Louis Godin’s—had in fact been coming and going from Cuenca ever since June, for they had used a bell tower in a church in the city’s

plaza mayor

as a triangulation point. Yet when they returned on August 23, they found the city all stirred up, like a bee’s nest that had been disturbed. Tensions were so high that Senièrgues, who had been living in Cuenca since March, did not dare go out in public without a loaded pistol.

Since the expedition had left Quito, Senièrgues had rarely been with the others. As they moved south through the mountains, he had regularly gone ahead to the nearest city in order to hang out his shingle as a traveling doctor. In one town, he had removed cataracts from a rich merchant, who had rewarded him with a princely sum. Senièrgues, La Condamine wrote, perhaps with a touch of envy, was making a “fortune” in the New World. Initially, Senièrgues

had enjoyed similar success in Cuenca, but then he foolishly became involved in a lover’s quarrel.

One of Senièrgues’s patients, Francisco Quesada, had a beautiful daughter, Manuela, who had recently been jilted by her fiancé, Diego de Leon. Leon, a guitar-playing Lothario, had dumped Manuela for the daughter of Cuenca’s mayor, Sebastián Serrano. In order to get free of his marriage contract with Manuela, he had promised to pay her family a sum of money. But then he reneged, and the Quesadas asked Senièrgues if he would help collect the debt. This was clearly a delicate situation, and to complicate matters, as Senièrgues was making his initial overtures to Leon, he moved into the Quesadas’ house, prompting a great deal of gossip in town about what the doctor’s real motives might be.

Senièrgues’s initial discussions with Leon went poorly. Even though Leon had jilted Manuela, he still felt jealous on hearing rumors linking Senièrgues and his former girlfriend. Negotiations broke down completely after one of Leon’s slaves came to the Quesadas’ house and “loudly insulted” Senièrgues. As La Condamine later recounted, his friend immediately went looking for Leon:

“Senièrgues stopped Leon at a street corner and picked a fight with him. Leon, for an answer, pulled out a loaded pistol, which did not prevent Senièrgues from advancing with his saber in his hand toward Leon, with such a rush that he took a false step and fell. Those that accompanied Leon intervened and separated the two.”

This scene was soon being reenacted in every bar in Cuenca. The local men—would-be comics all—took turns mimicking the clumsiness of the great doctor, falling over their feet in an exaggerated way while shouting out a few words of badly pronounced French. And there things might have ended, except that a few of Leon’s friends continued to boil over with anger, a sentiment that gradually spread. No one could understand what the French were doing in their town in the first place, and now they were wooing their women and threatening people with their swords. Could this be allowed to stand? A local priest, Juan Jiménez Crespo, asked a Cuenca judge to start a criminal investigation of Senièrgues. His

crime, Crespo declared, was that he had stayed overnight in the house of an unmarried woman. The priest also denounced the French from his pulpit, further whipping up ill feelings toward the doctor, and such was the foul mood of Cuenca when La Condamine and the others arrived on August 23, hoping for a little peace and quiet.

E

VER SINCE ARRIVING IN

M

ANTA

, the expedition members had been running into this darker side of Peru, where violence was constantly in the air. In Quito, the French had enjoyed the parties thrown for them and had been impressed by the fine clothes and refined manners of the Quito elite. But only a few blocks away from the elegant

plaza mayor

, they had discovered, “troublesome activities” began. There they found mestizos and others stumbling about drunk, thieves so bold that they would “snatch a person’s hat off” and run, and, most disturbing of all, Indians being dragged about by their hair as they were taken to work in the

obrajes

, or textile mills. Ulloa and Juan were carefully compiling notes on this aspect of Peru as part of their planned report to the king of Spain, and Cuenca, they wrote, was a particularly hard place: The men “have a strange aversion to all kinds of work. [Many] are also rude, vindictive, and, in short, wicked in every sense.”

At the root of this “evil,” as Ulloa and Juan dubbed it, was an economic system built on the forced labor of Indians. In the colony’s early years, the exploitation of the Indians had been accomplished through the encomienda laws, which placed entire native villages under a Spaniard’s control. However, this gave the spoils of Indian labor to a few, and the Crown quickly realized that the resulting concentration of wealth would nurture an aristocracy so powerful that it could challenge the authority of a distant monarchy. Spain passed legislation making it difficult for encomenderos to pass their encomiendas on to their descendants, and by the end of the sixteenth century, it had put in place a new system of compulsory labor.

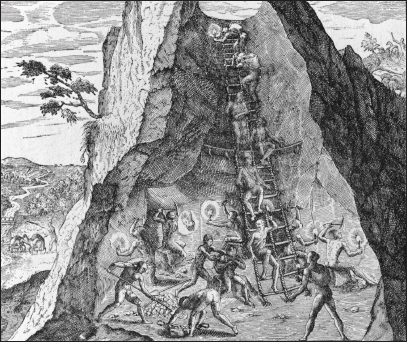

Indians in mita service mining silver.

By Theodore de Bry. Private collection/Bridgeman Art Library

.

The labor law, which was known as the

mita

, required a percentage of the population in every Indian village to work for several months each year in mines, textile mills, and haciendas owned by the colonists. The responsibility for doling out this labor to the colonists was left up to the corregidors, who were agents of the Crown. The Indians were paid fixed wages for their work, which made the mita, in the eyes of the Spanish monarchy, fair and just. But as Ulloa and Juan documented, the reality in eighteenth-century Peru was quite different:

Work in the

obrajes

begins before dawn when each Indian enters his assigned room. Here he receives his work for the day. Then the workshop overseer locks the doors, leaving the Indians imprisoned in the room. At noon he reopens the doors to allow

the laborers’ wives to deliver a scant meal for their sustenance. After this short interval, the Indians are again locked up. In the evening when it is too dark to work any longer, the overseer collects the piecework he distributed in the morning. Those who have been unable to finish are punished so brutally that it is incredible. Because they seemingly do not know how to count any lower, these merciless men whip the poor Indians by the hundreds of lashes. To complete the punishment, they leave the offenders shut up in the room where they work or place them in stocks in one of the rooms set aside as a prison.

The physical abuse of Indians conscripted into mita service was never-ending. Those who kicked too much while being dragged off to work were tied by their hair to a horse’s tail and brought in that manner to the shop. Ever since the 1500s, authorities had required Indians to keep their hair long so that they could be shunted about in this way. The whip used to punish the Indian laborers, Ulloa and Juan added, was “about a yard long, a finger’s width or a bit less, made of strands of cowhide twisted together like a bass guitar string, and hardened.” When a whipping was ordered, the Indians were

commanded to stretch out on the ground face down and remove their light trousers. They are then forced to count the lashes given them until the number set by the sentence has been inflicted. After getting up, they have been taught to kneel down in front of the person who administered the punishment and kiss his hand, saying, “May God be pleased, and may He give you thanks for having punished my sin.”

At times, in order to inflict more pain, the overseers would light two bundles of maguey stems on fire and then beat the bundles together

“so that the sparks fall on the victims’ open flesh as they are being whipped.”

Indians assigned to work on rural haciendas fared only slightly

better. They would be assigned the task of caring for a flock of sheep or a herd of cattle, and although they might not be subjected to the same steady physical abuse that obraje workers were, they were certain to lead hopelessly impoverished lives. In theory, Spain had outlawed the enslavement of Indians, but the way the system worked ensured their bondage. A shepherd caring for a flock of 1,000 sheep was paid fourteen to eighteen pesos a year. Out of this, Ulloa and Juan found, the Indian was expected to pay a tribute—an annual tax that all Indians between the ages of eighteen and fifty-five were expected to pay—of eight pesos. Each month, the Indian laborer was also forced to buy a 100-weight bag of corn at inflated prices, which cost him a total of nine pesos annually. If a sheep died or wandered off, the shepherd had to pay for it. In this manner, an Indian drafted into the mita ended up perpetually in debt and thus “remains a slave all his life,” Ulloa wrote.

This exploitation of Indian labor colored every aspect of Peruvian culture. Since those at the top of the rigid caste system looked down upon manual labor, so did those lower on the totem pole, and every group sought to dominate the one below it. The Creoles and Spaniards looked down on everyone who was not white, mulattos and mestizos fancied themselves better than Negroes, and everyone lorded it over the Indians. Even slaves could be seen dragging Indians about by their hair, and at one home Ulloa and Juan visited, slaves went out into the street and corralled Indians to do

their

work.

The clergy in Peru—save for the Jesuits, Ulloa and Juan reported—were equally abusive and corrupt. They were supposed to save the Indians’ souls, but their attention more often than not was focused on a decidedly worldly concern: making money. Clergy would bid for the right to tend to a parish and then apply

“all their efforts to enriching themselves.” Priests would not say mass until they had received gifts, and Indians who did not bring a gift or lacked goods to give were whipped. One priest reported that while traveling through his parish over the course of the year, he collected

more than 200 sheep, 6,000 chickens, 4,000 guinea pigs, and 50,000 eggs, all of which were profitably resold.

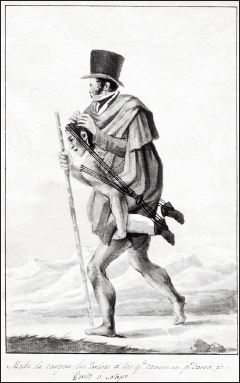

An Indian porter carrying a Spaniard.