The Mapmaker's Wife (26 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

With its rich soil and pleasant weather, Riobamba attracted a number of eminent families, whose names told of nobility and purity of blood. Also living there were many men who could boast of high military rank—sergeants, captains, and generals of the cavalry or infantry. These families, Ulloa noted in his journal, had

“been very careful not to diminish either the luster of their families, or their wealth, by promiscuous alliances, marrying only into one another.” The Maldonados were one such clan in Riobamba, and several others could trace their roots back to the conquistadors. These wealthy families built several churches that were equal in grandeur to any in Quito, and the one that graced the

plaza mayor

, they liked to boast, had a

“steeple that was the tallest in the viceroyalty.”

In 1699, the city was nearly destroyed by an earthquake, which killed more than 8,000 people in Riobamba and other Andean towns along the fault line. But the survivors rebuilt their beloved town, erecting homes of light stone and adobe that were, for the most part, only one-story tall, lest another earthquake strike. In the

ensuing decades, Riobamba reached the peak of its flowering, and people in other parts of the viceroyalty spoke of its “splendor.” More than 16,000 people lived in the city, and the surrounding fields were so fertile, sown with clover and various cereals, that—as Ulloa wrote—it created a

“landscape elegantly adorned with such an enchanting variety of colours as painting cannot express.” This agricultural bounty was complemented by profits from the textile business. Huge flocks of sheep grazed in the rolling hills above the valley, providing the raw wool for more than twenty textile mills in the district. The town’s location, with Quito to the north, Cuenca to the south, and Guayaquil to the west, also made it a vital transportation hub. All of this economic activity in turn attracted a number of jewelry makers, painters, carpenters, and sculptors, their work gracing the sumptuous parlors and dressing rooms in the homes of the elite.

Most wealthy families in Riobamba owned both a country hacienda and a city house, and that was true of the Gramesóns as well. They acquired a large hacienda called Subtipud in Guamote, a village about fifteen miles south of Laguna del Colta, where they produced potatoes and barley. Isabel also purchased several vegetable gardens in Chambo, which was ten or so miles to the east of Riobamba, and some other small properties in that area. Nearer to Riobamba, she bought several alfalfa fields from Franciscan nuns. The fact that she owned these properties in her own name reflected yet another contradiction of colonial Peru: Although elite women were not supposed to work and were expected to stay sheltered in their homes, they nevertheless did enjoy certain legal rights that provided them with a measure of independence. Such laws were the work of humanists in Spain who, since the sixteenth century, had sought to make Spanish society more equitable and just. Even the marriage dowry theoretically remained the property of the woman; the husband was supposed to safeguard these assets during their lives together, and then it would be returned to her upon his death.

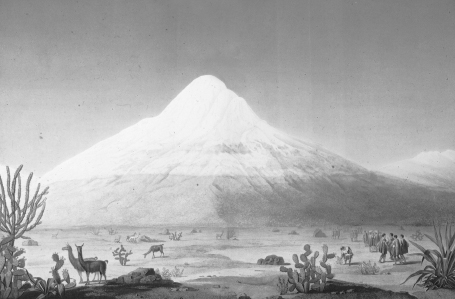

In Riobamba, Jean and Isabel lived on the east side of town, just up from the main square. As their home was on the side of a hill,

fifty feet or so above the valley floor, they had a particularly good view of Mount Chimborazo when they stepped out their front door, and if they climbed up the hill a few blocks more, to the top of the ridge, they could see a number of volcanoes in the snow-capped eastern cordillera. To the north was graceful Tungurahua and closer by was rugged Altar, and these volcanoes, forever rumbling and threatening to erupt, were like living entities to the people of Riobamba. One tale handed down from the local Indians told of the three volcanoes being involved in a messy “affair.” Massive Chimborazo was married to slender Tungurahua, but Tungurahua had betrayed Chimborazo in the past, having had a passionate romance with fierce-looking Altar. How could Chimborazo not notice such goings on? One day Chimborazo had looked out over the entire valley and had blown his top in fury, putting an end to the adulterous liaison. And now when Tungurahua spit smoke and

fire, locals mused that she must be remembering her old lover and was displaying her anger with Chimborazo for having denied her such pleasure.

Mount Chimborazo. Eighteenth-century drawing by Alexander von Humboldt.

By permission of the British Library

.

The constant rumblings of the earth influenced the religious habits of the people of Riobamba as well. They constructed a large statue of the Virgin Mary atop a nearby mountain, and from this lofty perch she looked over the town and protected them from nature’s wrath. On holy days, the priests would lead a procession to the foot of the statue, the people of Riobamba hopeful that their veneration of the Virgin would keep them safe.

While social life in the town centered on the church, as it did in all Peruvian cities, the people enjoyed their games too. Dice and cards were common pastimes, bullfights were held in the

plaza mayor

at regular intervals, and the city was known throughout the audiencia for its cockfights. The young boys in town also crowded neighborhood plazas to play

un juego con una pelota

(a game with a ball), which led church fathers at times to complain about their rowdiness. An attorney for the San Augustín Church wrote to the cabildo,

There are a great number of young people of bad habits that have established a ball game that has demoralized the spirituality of my convent. They block the street where they gather, and so many are they that they impede the path to the church and that doesn’t allow us to celebrate mass.… Furthermore, the ball strikes the convent and causes cracks in the walls, all to the disadvantage of said convent.

The Gramesóns prospered in this lively town. General Pedro Gramesón enjoyed a society where so many had titles—at mass, the pews would be crowded with men wearing medals and other insignia that told of their importance. Isabel’s older brother Juan became a priest in the San Augustín order, while her younger brother, Antonio, helped manage Subtipud. Antonio married and some years later became the father of two boys. Isabel’s younger sister,

Josefa, also wed, and she became the mother of several children. The one person who struggled in Riobamba was Jean Godin. He helped out with the Gramesón properties and continued to trade in textiles, but his business ventures in Riobamba were as unsuccessful as they had been in Quito. Every year he filed a list of his debtors with the town council, and every year it got longer. He simply was not good at getting people to pay him what they owed.

While he and Isabel never stopped talking about France, the years began to slip by. He continued to work on his grammar of the Incan language, always thinking of the moment he would present it as a gift to the king. Since Isabel spoke Quechua, she was able to help him in this endeavor. But they had set down roots in Riobamba—Isabel’s family was here and she was a property owner as well—and any possibility of going to France was delayed time and again by her repeated pregnancies. They had a second child and then a third, although each time the joy of birth was followed by grief. Neither child lived more than a few days, and with each death Isabel fell into a period of melancholy. Even Jean began to wonder if he would ever see Saint Amand again. His plans for traveling down the Amazon grew ever dimmer, until, in late 1748, he received a letter, written

eight years earlier

, from his siblings. His father had died, and his family wanted him home at once.

A

LTHOUGH

P

ORTUGUESE SLAVE TRADERS

had been regularly making their way up the lower part of the Amazon since the early 1600s, by the late eighteenth century, only a few people had ever traveled from the Andes down the river to the Atlantic coast. Indeed, when La Condamine set out, only three or four parties had ever made the 3,000-mile trek, there was no good map of the river, and fantastic tales of Amazon women and El Dorado still swirled about.

The mouth of the Amazon, which is a delta more than 200 miles wide, was discovered by Vicente Yáñez Pinzón, a Spaniard, in 1500. He named it La Mar Dulce, the Sweet Sea. According to the

1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, in which Spain and Portugal divided up the undiscovered world, this part of the New World belonged to Spain. But the coast here was not inviting. To the north were dense forests and swamps, and traveling southeast was difficult because of trade winds and shallow reefs. The Spanish attempted to establish a colony in the mouth of La Mar Dulce in 1531 but quickly gave up, and efforts to explore the Amazon from this direction lay dormant for the next seventy years.

From high up in the Andes, however, the conquistadors could look out at the vast jungle below and dream of riches hidden there. After Pizarro’s conquest of the Incas, everyone was certain that there were other wealthy kingdoms to conquer, and rumors were rampant about El Dorado, where gold was said to be so plentiful that the king covered himself in gold dust and washed it off each evening. There were also stories of a magical land in the jungle where cinnamon trees grew. The bark of this tree could provide a fragrant spice highly valued in Europe.

Lured on by such accounts, Pizarro’s brother, Gonzalo, headed out from Quito in February 1541 at the head of a large army—220 Spaniards in clanking armor and 4,000 Indians—that brought with it 2,000 hogs, 2,000 hunting dogs, and vast flocks of llamas. This expedition was larger than the one Francisco had mounted to conquer the Incas, but it quickly bogged down in the dense rain forest at the base of the Andes, where Pizarro and his men were plagued by incessant rains and hordes of insects. Although this area was sparsely populated, whenever Pizarro did encounter Indians, he tortured them to reveal the location of El Dorado, and if they professed not to know, he had them burned alive or fed to the dogs. Finally, a local chief, having learned of such interrogation methods, told Pizarro what he wanted to hear—there was a fabulous kingdom ruled by a powerful overlord further to the east. Pizarro and his men wandered deeper into the wilderness until, at last, they came upon a navigable river, the Coca, a tributary of the Napo. Here they stopped long enough to build a small boat to carry their supplies and munitions. The horses and men, however, proceeded

on foot along the banks of the river, hacking their way through thick brush, and at the end of ten months, Pizarro and his band of men were still only 300 miles from Quito. They were also struggling to stay alive. They had eaten most of their animals, nearly all of the 4,000 Indians had died, and they had not discovered a speck of gold.

On Christmas Day 1541, Francisco de Orellana, who was the second in command, proposed that he take the boat and sixty men and head downstream in search of food. Pizarro agreed, a decision he came to rue, for he never saw Orellana again. At first, Orellana found nothing. There were no settlements along the river, and his troops were reduced to eating their leather belts and the soles of their shoes, which they cooked with herbs.

“They were like madmen, without sense,” wrote Friar Gaspar de Carvajal, who accompanied Orellana. But shortly after New Year’s Day, they came upon an Indian village, and after Orellana made peace with its chief, the villagers provided them with “meat, partridges, turkeys, and many kinds of fish.” They had found the food they had been seeking, but they had proceeded so far down the swift-moving river—as much as seventy-five miles each day—that they realized it would be impossible to return to Pizarro. After waiting three weeks to see if he would come to them, during which time they built a second boat, they decided that they had no choice but to go on without the others. Their only plan was to follow the unknown waterway to its end.

As they proceeded down the Napo, they entered a world that was more and more heavily populated, and shortly after they reached the Amazon, in mid-February, they came upon the kingdom of Aparia the Great, who brought them cats and monkeys to eat. Now they began encountering one “nation” after another—first the Machiparos, who were rumored to number 50,000, and then the even larger kingdom of the Omaguas, which stretched for several hundred miles. “We continued to pass numerous and very large villages,” Carvajal wrote, “and the farther we went the more thickly populated and better did we find the land.” The Indian

tribes, he reported, kept turtles in pens and often supplied Orellana and his men with eggs, partridges, parrots, fish, and a variety of fruit to eat, including pineapples, pears, plums, and custard apples.

By this point, the Amazon was so wide that they could not easily see from one side to the other. There was an endless horizon of green trees along the riverbank, the water moved languidly along, and lush clouds piled up overhead. In early June, they came upon a great river that flowed into the Amazon from the north, which they named the Río Negro after its inky black color. So powerful was this river that its black water did not completely mix with the Amazon’s brownish current for twenty leagues, Carvajal reported. Here they began to be attacked with some regularity by Indians, who paddled out in canoes to fight, at times firing so many arrows that the Spaniards’ boats looked like porcupines. Even so, Orellana reached the Atlantic in August 1542 with forty-nine of his men still alive. Only eleven had died on the long journey, and eight of the deaths had been due to “natural causes.” While he had not found El Dorado, he had discovered a populated world, where food was abundant and the natives were variously welcoming and hostile. Carvajal also told of a tribe of women warriors on the banks of the river, below the Río Negro, and of an encounter with four giant white men. As a result of his account, La Mar Dulce came to be known as the River of the Amazons.