The Most Evil Secret Societies in History (11 page)

Read The Most Evil Secret Societies in History Online

Authors: Shelley Klein

We know that much of the bush-meat trade is used in potions and ointments for black magic treatments and we know that other animals are sacrificed for voodoo purposes in the African community. But we have a very deep concern over human body parts. We think they could be coming in with the bush meat.

10

As recently as May 2005, the London Metropolitan Police reported that over a two-month period as many as 300 black children aged between four and seven years old have vanished from school registers within the British capital. Many believe this to be a conservative estimate and some experts put the figure much higher with thousands of children disappearing from the school system each year. Most of these are not thought to come to any harm, but if just one child is abused or murdered, it is one child too many. Barbara Hutchinson, the deputy chief executive of the British Association of Adoption and Fostering has stated that she is horrified at the figures. âMany privately fostered kids,' she said, âget passed on from household to household. They may be moved around to avoid immigration control; they may be exploited. We know some children are being trafficked to be used as domestic servants or for sexual exploitation.'

11

Similarly, Chris Bedoe, the director of End Child Prostitution, Child Pornography and Trafficking for Sexual Purposes has stated that governments worldwide are failing to take the problem seriously enough. Indeed, she has gone on record as saying their failure could be responsible for the sexual exploitation of large groups of children and numerous deaths. âWe heard recently,' she said, âof a thirteen-year-old girl who told her teachers her parents had gone home and left her on her own in the UK, and some time later she too disappeared. The teachers don't know what happened to her. We are hearing this type of thing all the time.'

12

Bearing this and all of the other evidence in mind, it seems that, although Adam's case was probably the first of its kind in London, it will almost certainly not be the last.

I remember in the last of the Tong Wars there was a guy named Wong Quong, who was killed on January 6, 1926, in Ross Alley. And on April 20, Ju Shuck was killed in the back of the Chinese Theater (at 420) Jackson. They were all from different Tongs, and we knew they'd been killed because of a war, but we could never figure out just who did it. The Chinese were a secretive lot anyway, by and large, but none of them could talk about a murder like that. They would have been violating the code.

D

AN

M

CKLEM

,

Chinatown Tong Wars of the 1920s

, Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

L

ong before the Tongs and the Triads became known worldwide for their criminal activities, they operated as resistance organizations in seventeenth-century China, established to fight against the Ching, who had taken over their country. The Ching were not popular with the majority of Chinese as they originated in Manchuria, a country to the north of China.The Manchus invaded China in 1644, overthrowing the ruling Ming emperor to establish the Ching Dynasty.

From the very beginning, Ching rule was marred by difficulties. Apart from the resentment that was caused by having a non-Chinese governing body, its rule was also beset by the ever-increasing presence of foreign colonial powers that were seizing sizeable tracts of Chinese territory and insisting that China allowed the import of large amounts of foreign goods into the country. This was upsetting the finely balanced Chinese economy, making the harsh life of the average Chinese citizen even harder, and creating a breeding ground for dissent and planned insurrection. The resistance was fostered within the folds of the secret societies â the Tongs and the Triads â which, right up to the twenty-first century have struck terror into the hearts of millions of ordinary people all over the world.

The family name of the Ming emperors, for whose return these secret societies were fighting, was âHung' and many of these organizations incorporated the Hung name into the name of their own group. Their name, however, was generally all any outsider might know about the group. Secret codes and clandestine rituals were adopted in order that society members could operate without detection. All members were required to learn the martial arts â something that came in very useful when these secret societies aided and abetted several rebellions against the Manchus, notably during the White Lotus Society rebellion in the mid 1790s, the Cudgels uprising between 1847 and 1850, the Taiping uprising between 1850 and 1864, and the Boxer Rebellion which took place between 1896 and 1900. However, unfortunately for those supporters of the former Ming Dynasty, when the Ching were eventually ousted from power in 1911, there were no Mings left to restore to the throne. Consequently, the first president of the newly formed Republic of China was a former military general by the name of Yuan Shikai. He was, unfortunately, no more able to rule the country than the average man in the street and China continued to flounder in an atmosphere of near-total political chaos. With the political leadership in disarray, the people looked elsewhere for guidance and reassurance. They turned to the secret societies which flourished as never before. For the majority of Chinese people, the most significant event of the early twentieth century was the first wave of Chinese emigration to America. Suddenly a whole range of âChinatowns' sprang up all the way down both the west and east coasts of the USA. These communities not only gave the new Chinese settlers a sense of âhome' in their otherwise foreign surroundings, but they also had a secondary, far more sinister, role to play. The different Chinatowns served to facilitate the establishment and growth of those Chinese secret societies that had wielded so much influence back in the old country. Two groups in particular were of special importance: the Tongs and the Triads.

Defining precisely what the Tongs represent is a complicated affair because it involves a cursory knowledge of how Chinese society operates. Originally the word was an anglicization of the Mandarin

tang

, meaning a lodge or a hall, although this generally referred to the group operating within such a hall, rather than to the building itself, much as a Masonic Lodge refers to the members of the society rather than the place in which they meet and a âchurch' can be the congregation as much as it is the building where the congregation worships.

A Tong group consisted largely of âunrelated Chinese people united to assist one another by a bond that includes secret ceremonies and oaths.'

1

Traditionally, therefore, whenever the Chinese found themselves transplanted en masse to new surroundings, as they did when the emigrated to Canada or America, the Tong would be one of the first organized groups to set up operations. A prime example of this occurred in British Columbia in 1862 when, on arrival in their new country, the Chinese immediately set about establishing the Chi Kung Tong to aid and abet them in both family and business matters. The Tongs were, and still are, deeply respected within Chinese society, due for the most part to their revolutionary history, in particular those times when they fought against the Manchus and the Ching Dynasty. The Chinese look back with pride on those days, revering the Tongs and bestowing on them an almost legendary status.

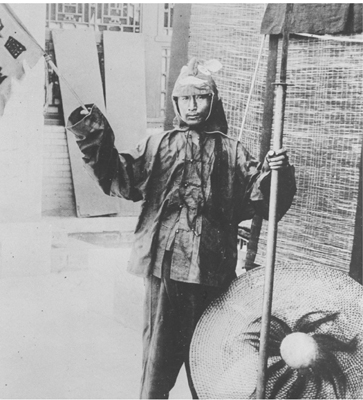

Tong and Triad secret societies provided many freedom fighters for the resistance movement against the Manchus, including this flag- and spear-carrying warrior from the Boxer Rebellion of 1896-1900.

Yet, had they relied on their revolutionary credentials alone, it is doubtful the Tongs would have survived. Instead the Tongs have fashioned themselves to serve as a particular type of social unit, looking after all those who belong to their group, ensuring their safety above all others, protecting their interests by any means available. In this way the Tongs have adopted the manners and values of that other, most Chinese of subcultures, the Triad organizations. Particularly in North America, where Tong groups sprang up in every major city, the society has provided a network of social contacts for its members. Naturally, where criminal activities are concerned these contacts prove incredibly useful, providing funds, manpower and weaponry. Indeed, it is the criminal element, more than any other, that comprises the majority of Tongs, for since their inception they have been renowned for running illegal gambling operations, drugs rings, extortion gangs and prostitution rackets. Where the latter is concerned, the Tong wars, which raged in America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, were almost entirely based on internecine warfare between different Tong gangs fighting over prostitution rackets.

From the moment the first Chinese settlers set foot on American soil, they began setting up Tongs and other secret societies to help establish themselves in their newly adopted surroundings. But one thing was in short supply: women.

From 1870 to 1910, the ratio of male to female Chinese immigrants in California (the primary point of entry for Chinese to the United States) was always at least 10 to 1, and a ratio of 20 to 1 was much more common. From 1881 to 1890, as little as 1 percent of the Chinese in America was made up of women.

2

Inevitably this shortage meant that Chinese prostitution rackets were incredibly lucrative: after all, those Tong gangs who set up Chinese whorehouses had a ready-made customer base, eager to pay over-the-odds for the product. And as for the âproduct' itself, in the nineteenth century the bulk of women involved in the trade would have been sold into it by their impoverished families back in China. A smaller percentage of girls would have been kidnapped, with only a very few volunteering to enter into the practice, in order (or so they believed) to earn good money which could then be sent back to relatives. Chinese girls were popular amongst America's white population, but their main source of income would have been amongst their own kind. This meant that a great deal of competition developed between different Tong gangs, all of which vied for the same trade in an attempt to gain bigger and bigger slices of the proverbial pie.

With so much money at stake, violence was never far from the scene. In 1864 the first Tong war erupted in America when a male member of the relatively large Suey Sing Tong gang kidnapped one of his rival's mistresses. Battle was declared, with several men on both sides being killed. The matter was only settled when the Suey Sings eventually caved in and returned the woman to her ârightful owners.' Disputes such as this broke out frequently between different Tong gangs, exacerbated by the fact that shipping prostitutes from China to America was a costly affair, making the prostitutes â for want of a better phrase â worth their weight in gold.

The preferred weapon of the Tong gangs during this period was a six-inch-long hatchet â a relic from their ancestral past, but one which also earned the Tongs a great deal of notoriety in America. Other weapons included knives and, of course, guns. The writer Herbert Asbury gives a fascinating insight into the type of weaponry and clothing worn by a typical nineteenth-century Tong âwarrior' along San Francisco's Barbary Coast: â[ â¦] their queues [pigtails] wrapped around their heads, black slouch caps drawn down over their eyes, and their blouses bulged with hatchets, knives, and clubs.'

3

When Tong warfare broke out, white journalists liked nothing better than to write up the events for the simple reason that it made great copy. Hatchets meant blood and blood ensured a large readership. Nowhere was this better illustrated than in Los Angeles in 1871 when two gangs, the Hong Chow Tong and the Nin Yung Tong, began fighting each other in a dispute over a woman. The fighting went on for days, during which time men on both sides were badly injured, whilst others were arrested. Finally one of the city's white sheriffs was shot in the shoulder whilst pursuing one of the Tong leaders. The injured man was rushed to hospital, but the wound was deep and became infected and eventually he died. Enraged by what they saw as a rising level of violence within the immigrant Chinese population, something in the region of 600 people mounted a mass demonstration through Los Angeles's Chinatown district during which further violence broke out. The man said to have been responsible for the sheriff's death was caught by the mob and subsequently lynched. The mob then looted and ransacked every Chinese property they could lay their hands on. In addition to the damage to property, the mob also attacked any Chinese man, woman or child they came across: it is estimated that a further nineteen Chinese were lynched while countless others were shot or hacked to death with their own hatchets. Eight white men were arrested that day and given jail terms, but none served longer than a year in prison.

These were horrendously tough times for the new immigrants and it is little wonder that after such incidents, Tong membership rocketed as more and more Chinese felt the need to stick to their own kind and keep all their dealings secretive. Possibly because of this secrecy, the rites of passage Tong initiates were required to take remained shrouded in mystery. Luckily, the same is not so true of the vows Triad members are said to undertake, which are no doubt similar (if not in content then in tone) to those of the Tong.