The Most Evil Secret Societies in History (14 page)

Read The Most Evil Secret Societies in History Online

Authors: Shelley Klein

Membership swelled rapidly, drawing into its fold all manner of disenfranchised white men. Although in the first flush its main aim wasn't to be a ânight-riding' organization, the Klan certainly emphasized 100 percent white supremacy. Then, when America became embroiled in the First World War in 1917, yet another role was assumed by the white brotherhood â that of maintaining law and order.

The nation was gripped by fear; it had to be defended against alien enemies, Roman Catholic subversion, and those who were politically motivated against the government â union leaders, strikers and draft dodgers. The Klan, therefore, felt it had a crucial part to play. Reveling in its role as a pseudo-secret-service organization, the Klan began not only keeping files on political activists, but also spreading its net to include bootlegging, corrupt business dealings, extra-marital affairs, anything, in fact, that it considered to be un-American. The strategy worked. By 1919 membership had reached several thousand but, even so, Simmons knew only too well that they had hardly begun to realize the Klan's full potential. He decided to employ a couple of key disciples to publicize the cause and drum up further membership. Edward Young Clarke and Mrs. Elizabeth Tyler, who formed the Southern Publicity Association, were the chosen two.

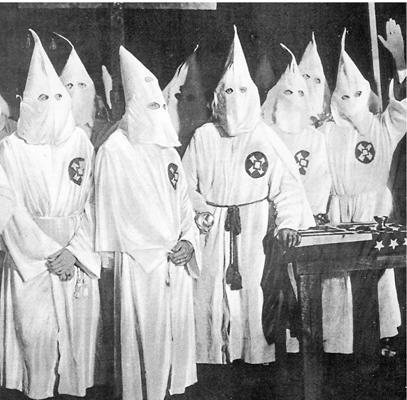

By 1921 the Invisible Empire (as it had become known) had grown in support to boast well over 100,000 members. There seemed to be no end to the number of white Protestant males who wanted to belong to this secretive, fraternal organization with its strange rituals and even stranger costumes.

Two years later the Klan managed to win a place in the United States Senate when one of its members, Earl B. Mayfield, was elected. Towards the end of that year a new Imperial Wizard, Hiram Evans, took over the reins of power from William J. Simmons and succeeded in recruiting even more Klan members. But with the swelling of the ranks came a rapid escalation in Klan violence. Even with the publication of a series of articles exposing the Klan's less than spotless record, membership was unaffected and the violent episodes increased. A newspaper exposé only added to the Klan's popularity, appealing in the main to the lower middle-class, religious fundamentalists who felt that mainstream politics had not just passed them by, but had dragged the entire country away from the kind of small-town Protestant values by which they set so much store. In contrast, the Klan allowed its members a vicarious power. Leonard Cline, a reporter for the

Baltimore Sun,

wrote:

It must have provided a real thrill to go scooting through the shadowy roads in somebody else's flivver, to meet in lonely dingles in the pine woods and flog other men, to bounce down the fifteen-foot declivity where the ridge ends and swoop at twenty-five miles an hour through the flatlands around Mer Rouge, through phantasmal Lafourche swamp with its banshee live oaks, waving their snaky tresses in the moonlight. It was perpetual Halloween. And even if one didn't care much for church, and took one's shot of white lightning when one could get it, and would pay a dollar any day for five minutes in a trollop's arms, it was reassuring to know that religion approved and sanctified one's pranks. It made one bolder.

3

There are many examples of floggings and lynchings from this period. The state of Texas was notorious for its tar-and-feather parties, and during the spring of 1922 the southern state was credited with having flogged as many as sixty-eight people in what became known as a special Klan âwhipping meadow' by the banks of the Trinity River. But perhaps one of the best-known Klan incidents took place in Louisiana. Two young black men, Watt Daniel and Tom Richards, were targeted for punishment by the Klan's Mer Rouge (in Morehouse Parish) outfit, at that time led by a Dr. B. M. McKoin. Daniel and Richards had been caught spying on Klan meetings and generally badmouthing the organization, so it was decided that the the two boys would be taught a lesson. After being kidnapped in broad daylight, they were taken to some woods and warned that their behavior was unacceptable. Then they were released. Sadly, however, the story did not end there. A few weeks later, on August 24, 1922, after a baseball game and barbecue which most of Mer Rouge had attended, Watt Daniel and Tom Richards, together with their fathers and one other unnamed man, were ambushed in their car, seized by masked figures, blindfolded, hog-tied and bundled into a waiting vehicle. The prisoners were then driven to a clearing in the woods, at which point the two elder men were tied to trees and flogged. Watt Daniel, seeing his father in distress, succeeded in breaking free from his captors, but in so doing tore off the hood of one of his assailants. In this moment it is thought that both he and Tom Richards recognized their tormentor. Their fate was duly sealed, for while their fathers and the unnamed man were later released, Watt and Tom were dragged further into the woods never to be seen alive again.

Klan members gather in full regalia at an initiation ceremony not in the âDeep South', as one might expect, but in Baltimore in 1923.

Back in Morehouse Parish there was a public outcry. Pro- and anti-Klan factions were at each other's throats, ready to fight one another to the death over what had occurred. The Democratic governor of the state, John M. Parker, had lost control. So serious was the situation that he had personally requested help from the Justice Department in Washington. After much deliberation, however, President Harding felt his administration did not have the jurisdiction to take the case further. Governor Parker would therefore have to act alone, a prospect he did not relish. Eventually, he ordered the dragging of a lake where it was thought the bodies of the two boys lay and, after several setbacks, the corpses were recovered. A coroner confirmed they had been flogged and later crushed to the point that every bone in their bodies had been broken.

There then followed a protracted period of time while evidence was gathered against Klan members, but as is the way with any secret society, it proved virtually impossible to identify the culprits. In the small number of cases where there was enough evidence to proceed, two successive grand juries refused to indict anyone, not least because sitting on the said juries were several influential Klan members. The most Governor Parker could do was to attempt to convict some of those involved for minor misdemeanors, which he did with varying degrees of success. Some of the culprits were given small fines, while others left the county never to return.

Parker made it known that no district judges would be appointed if they were known to be Klan members, and in state elections during 1924, all of the candidates for the governorship declared themselves anti-Klan. Was this the beginning of the end for the Invisible Empire? The answer is less than clear, for although the organization was on a downward spiral in several key states, including Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma and California, membership had reached a peak during the mid-twenties, when it numbered approximately three million. By 1928, however, only a few hundred thousand remained.

Several key factors contributed to this decline. With the end of the First World War, Americans felt more secure and the economy appeared to be picking up, signaling greater prosperity for all. The Klan also had to battle the negative publicity caused by events such as the Mer Rouge murders, together with a handful of other notorious cases including the murder of a police constable which took place in Inglewood, California. The state of Texas's flogging parties were also proving a severe embarrassment. Suddenly, law-abiding citizens began to see the Klan as a divisive force, disrupting communal harmony, causing civil unrest. Many of those who had previously belonged to the organization wanted to distance themselves from it. Even with the onset of the Depression, when it might be thought that the Klan would see a swelling of its ranks, membership dwindled even further. Large swathes of the country were out of work and quite literally starving, yet the best the Klan could come up with was to announce that anyone involved in civil unrest such as hunger marches were nothing better than âNegroes, Hunks, Dagoes, and all the rest of the scum of Europe's slums.'

4

By the late thirties, it seemed that nothing could revive the Klan's fortunes, and as if mirroring this decline, Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans retired. Taking over from him was a man by the name of Jimmy Colescott. Colescott immediately put into action a major recruiting campaign, which included the usual Klan tactics of violence and intimidation. However, it was doomed to failure from the start for, alongside the onset of the Second World War, which effectively concentrated everyone's minds elsewhere, major incidents such as the âShoemaker flogging' brought nothing but adverse publicity.

Consistently against any kind of organized labor or union membership, the Klan was particularly active in the citrus state of Florida where, in 1935, a political group (the Modern Democrats) began trying to create several labor organizations, as well as campaigning for employment reform. Ever alert to such threats, the Klan sent an undercover agent to spy on the Modern Democrats and, after one meeting of members, they detained several men whom they suspected of being key players in the new movement. Among those detained was Joseph Shoemaker. Shoemaker was taken away, flogged, castrated and tarred all over before having one of his legs plunged into a vat of boiling tar. Nine days later he died of his injuries. Though the incident brought national condemnation, and despite the arrest and trial of several of those responsible, ultimately no one was convicted of Shoemaker's murder.

Drawing confidence from this blatent evasion of justice, the Klan then tried to regroup and regain some lost ground over the next decade, particularly where recruitment was concerned, but Imperial Wizard Colescott didn't seem up to the job, and with the Second World War drawing to a close, Grand Dragon Dr. Samuel Green took over Colescott's position. Reintroducing parades, mystic initiation ceremonies atop Stone Mountain, night raids and floggings, he did his best once again to swell the Klan's ranks. But his recruitment drive was beset by problems, mainly caused by bodies such as the FBI and the Bureau of Internal Revenue, which were keeping a close eye on the white-hooded society.

In 1949, Samuel Green died suddenly, plunging the Invisible Empire into even greater turmoil. Splinter groups formed, creating numerous factions that each clung desperately to its own violent agenda. Burning crosses could be spotted across the whole of the south and yet, although united in violence, the Klan could still not rally around one leader to form a cohesive political whole. One result of this was that many Klan leaders ended up in jail. Even with the abolition of public-school segregation, which took place on May 17, 1954, the Klan could not unite properly.

Violence was the only factor that brought the Invisible Empire together, a fact which is illustrated horrifically in the following extract from a report by the combined forces of the Friends' Service Committee, the National Council of Churches of Christ and the Southern Regional Council, which lists over 500 cases of intimidation and violence after the passing of the Supreme Court's school decision.

â¢â

6 Negroes killed;

â¢â

29 individuals, 11 of them white, shot and wounded in racial incidents;

â¢â

44 persons beaten;

â¢â

5 stabbed;

â¢â

30 homes bombed; in one instance (at Clinton, Tenn.), an additional 30 houses were damaged by a single blast; attempted blasting of five other homes;

â¢â

8 homes burned;

â¢â

15 homes struck by gunfire, and 7 homes stoned;

â¢â

4 schools bombed, in Jacksonville, Nashville, Chattanooga, and Clinton, Tenn.;

â¢â

2 bombing attempts in schools in Charlotte and Clinton;

â¢â

7 churches bombed, one of which was for whites; an attempt made to bomb another Negro church.

5

But if the violence of the 1950s was horrific, during the 1960s, with the ever increasing influence of the civil-rights movement and the fact that the black population was becoming a growing economic competitor to the working-class white male, it only escalated. The Klan finally succeeded in appointing a new Imperial Wizard, a man who, if not accepted by every Klan member, was at least favorable to the majority. Robert Shelton was a Tuscaloosa rubber worker who harbored a violent dislike of black people, whom he saw as little more than savages. With Shelton at the helm, the Invisible Empire slowly began to claw back some degree of coordination, and once again began to make life for its black victims barely tolerable. Nowhere was this more apparent than in Birmingham, Alabama where, during the early part of the 1960s, bombing of black homes and businesses became an almost weekly occurrence until, on September 15, 1963, one of the most infamous crimes in American history was committed when the Klan bombed the Sixteenth Street Bethel Baptist Church, killing four young girls â Cynthia Wesley, Dennise McNair, Carol Robertson and Addie Mae Collins.