The Most Evil Secret Societies in History (18 page)

Read The Most Evil Secret Societies in History Online

Authors: Shelley Klein

T

hese days, the word âassassin' is common parlance, used to define any murderer of an important person or anyone hired in the role of professional killer, but originally the word came to the West via the Arabic language just before the time of the Crusades, when it was used to denote a secretive Islamic sect feared throughout that region for the many murders it committed. The Hashishim (also referred to as the Ismailis or the Assassins) were a group who became infamous for using murder as a political weapon. Unpitying, merciless and ruthlessly systematic in both the planning and execution of their crimes, this radical Islamic sect was, justifiably, one of the most feared organizations in the world at that time.

First mention of the group is believed to be in the report of an envoy who was sent to Egypt and Syria in 1175 by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa.

Note, that on the confines of Damascus, Antioch and Aleppo there is a certain race of Saracens in the mountains, who in their own vernacular are called Heyssessini [â¦] This breed of men live without law; they eat swine's flesh against the law of the Saracens, and make use of all women without distinction, including their mothers and sisters [â¦] They have among them a Master, who strikes the greatest fear into all the Saracen princes both far and near, as well as the neighboring Christian lords. For he has the habit of killing them in an astonishing way.

1

This âMaster,' who was best known by the sobriquet âThe Old Man of the Mountain' (a nickname which was passed down from one Assassin leader to the next), wielded tremendous power over his followers, engendering in them a fanatical devotion that admitted no other master.

The explorer Marco Polo, who traveled through this part of the world in 1273, made some interesting observations relating to the Old Man, observations that go some way towards explaining the hold he had over his followers. Polo described how the Old Man had established a âcertain valley between two mountains to be enclosed, and had turned it into a garden, the largest and most beautiful that was ever seen, filled with every variety of fruit.' Polo then goes on to explain how the Old Man required his followers to believe that this garden was actually Paradise. âNow,' writes Polo, âno man was allowed to enter the Garden save those whom he intended to be his ASHISHIN.' Once the Old Man had selected those he wished to enter, they were given a potion to drink after which they would fall asleep, then be carried into the garden. On waking in such beautiful surroundings the Old Man's victims would immediately believe they were in Paradise. And here they would remain until he needed one of them to return to the outside world as an assassin. The chosen one would once again be given the sleeping potion, only this time he would be carried out of the garden and on awakening be given his instructions. âGo thou and slay So and So,' wrote Marco Polo in imitation of how the Old Man spoke, âand when thou returnest my Angels shall bear thee into Paradise. And should'st thou die, nevertheless even so I shall send my Angels to carry thee back into Paradise.'

2

Venetian traveler and explorer Marco Polo came across the cult of the Hashishim when traveling through the Middle East in 1273 â and wrote extensively about the âOld Man of the Mountain.'

Whether the above account is true or not (and many historians for a variety of reasons believe it is not), what it does illustrate is the extent to which the Hashishim had invaded public consciousness. By the twelfth century several commentators thought they detected the Hashishim's hand behind all kinds of political murder, not just in Syria but also in Europe. In 1158, while Frederick Barbarossa was laying siege to Milan, one historian alleges that an âAssassin' was caught in Barbarossa's camp. In 1195 while the English King Richard I âLionheart' was sojourning at Chinon, it has been documented that at least fifteen Assassins were captured and later confessed to having been sent by the King of France to kill him. Numerous other accounts began to filter through and before long it became commonplace to accuse your enemy of being in league with the Old Man of the Mountain for the sole purpose of having you assassinated. The truth is that most European leaders of those times would not have needed any outside help to rid themselves of their enemies by murdering them, so the accusation was actually something of a goading insult.

Nevertheless, the Hashishim continued to arouse Western curiosity and in 1697 a man by the name of Bartholomé de Herbelot wrote a book called the

Bibliothèque orientale

(The Oriental Library) which contained almost all the information then available on the history, religion and literature of this region. The Assassins, so de Herbelot concluded, were an offshoot of the Ismailis (who were themselves an offshoot of the Shi'a, whose quarrel with the Sunnis was, and still is when one looks at modern-day Iraq, the main religious schism in Islam).

Another major study â though from a considerably later date â was by the Arabic scholar Silvestre de Sacy, who posed the theory that the Hashishim were so called due to their liberal intake of hashish; however, this theory was later discredited as the Ismailis never make mention of this drug in their texts. It is also believed that

hashishi

â a local Syrian word â was a term of abuse given to the sect to describe their unsociable behavior, rather than a reference to any drug. Indeed, so âunsociable' was the Hashishim's behavior that it is thought the original Old Man of the Mountain â a man by the name of Hasani Sabbah â didn't leave his mountain retreat for well over thirty-five years.

Sabbah was born in the city of Qumm, around the middle of the eleventh century, but while he was still a young boy his father moved the entire family to Rayy (nowadays known as Tehran), where Sabbah began his first serious attempt at religious education.

From the days of my boyhood, from the age of seven, I felt a love for the various branches of learning, and wished to become a religious scholar; until the age of seventeen I was a seeker and searcher for knowledge, but kept to the Twelver faith of my fathers.

3

It appears that Sabbah visited Egypt for a period of approximately three years, staying first in Cairo and afterwards in Alexandria. It was during this time, however, that he turned away from his former faith due to a split within the religion. On his deathbed the Caliph of Cairo, al-Mustansir, had appointed his son, Nizar, to succeed him, but after he passed away a decision was made whereby Nizar's brother, a man by the name of al Musta'li, was made Caliph instead. This caused huge disturbances among the population, with many people choosing not to recognize al Musta'li.

The dissenting group proclaimed their allegiance to the by-passed Caliph Nizar, and it is for this reason that members of the sect which became known to history as The Assassins were first known as the Nizari Isma'ilis.

4

Hasan-i Sabbah aligned himself with this latter sect, a decision which later saw him deported from Egypt to North Africa. But the ship he was traveling on ran into difficulties, although he was rescued and taken to Syria. From here Sabbah traveled throughout Persia, also visiting Iran and Kurdistan. His main interest, however, lay in northern Persia in the Shi'ite stronghold of Daylam. This was a place that in the words of Bernard Lewis âjealously [guarded] its independence against the Caliphs of Baghdad and other Sunni rulers.'

5

As someone who himself shunned the Caliphs, Hasan-i Sabbah fitted in well with his new surroundings and made every effort to put into practice the ânew' preaching of the Nizari Ismailis, traveling extensively throughout the region until, three or four years later, he decided he needed a permanent base for his teachings. He chose a mountain hideaway which would be inaccessible to his enemies, but from where he could continue his fight not only against the Caliphs, but also against his true enemy, the Seljuq Empire.

In the eleventh century, the Islamic world suffered a series of major invasions, the most serious by the Seljuq Turks, who eventually established a new empire that stretched from Central Asia right through to the Mediterranean. It seemed that the Seljuq were invincible. No one attacked them, no one challenged them. Their military power was second to none, and the only form of dissent came from the Ismailis and in particular from Hasan-i Sabbah who, over the years, fashioned himself into the Seljuq's worst nightmare.

When Sabbah first decided to establish a mountain stronghold, the only place he knew of where all the criteria he demanded existed, was the castle of Alamut. Built more than 6,000 feet above sea level on a narrow ridge in the heart of the Elburz Mountains, dominating a sheltered valley that stretched for approximately thirty miles, Alamut was the perfect location. The building is rumored to have been constructed by a former King of Daylam who, while out on a hunting expedition one day, let loose an eagle that alighted on a rock high in the mountains. Seeing how well positioned the location was, the king immediately ordered a castle be built on the site, thereafter naming it Aluh Almut, which in translation means âEagle's teaching'. It was rebuilt in 860 by yet another king, but when Sabbah decided the castle was to be his, he overthrew the building's old incumbent and established himself as the new master of Alamut.

Once Sabbah entered the building, he never again returned down the rock on which the castle was built. Instead, he led an abstemious life, studying, preaching and looking after the affairs of his âkingdom' which, for the main part, meant winning over new converts to his cause and gaining possession of more castles. He also sent out missionaries to help him accomplish both aims. The historian Juvaynie wrote:

Hasan exerted every effort to capture the places adjacent to Alamut or that vicinity. Where possible he won them over by the tricks of his propaganda while such places as were unaffected by his blandishments he seized with slaughter, ravishment, pillage, bloodshed, and war. He took such castles as he could and wherever he found a suitable rock he built a castle upon it.

6

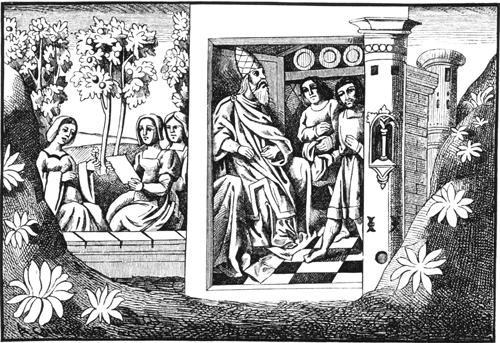

This illustration from the fifteenth-century manuscript

Travels of Marco Polo

shows the Old Man of the Mountain issuing his deadly orders to his followers.

So successful was Hasan-i Sabbah, that his operatives even began spreading their religious propaganda in areas loyal to the Sunnis and the Seljuq. It was Sabbah's operatives who first drew blood in a Seljuq-controlled area of Rayy. Eighteen Ismaili agents, who had gathered together to conduct prayers, were placed under arrest by local guards. They were questioned, after which they were released. The group then went on to try to convert a muezzin, but this man refused to accept their religious teachings and, fearing that he might report them to the authorities, the group killed him. Hearing about the death, the Vizier of the area, Nizam al-Mulk, gave an order that the group's ringleader be arrested and executed â an order that was swiftly carried out. This was the first of many subsequent crack-downs on the Ismailis by the Seljuqs, but rather than shy away from future conflict, the Ismailis, under Sabbah's leadership continued to fight back, and were soon employing the art of assassination to aid them in their task.

Their first chosen victim was said to be the Vizier himself, Nizam al-Mulk, and the man chosen to carry out his murder was Bu Tahir Arrani.

[â¦] on the night of Friday, the 12th of Ramadan of the year 485 [October 16, 1092], in the district of Nihavand at the stage of Sahna, he came in the guise of a Sufi to the litter of Nizam al-Mulk, who was being borne from the audience-place to the tent of his women, and struck him with a knife, and by that blow he [Arrani] suffered martyrdom.'

7

Nizam al-Mulk's assassination was only the first in a long line of political killings that then erupted. No one was safe: princes, kings, generals, viziers, governors, divines â anyone who professed to disagree with the Ismailis and their teachings was considered an enemy and became a legitimate target. The Ismailis considered themselves an elite killing force, striking down all those who opposed them. Their victims, on the other hand, regarded the Ismailis as nothing more than âcriminal fanatics,' men who were willing to break the law and commit murder to get their own way.