The Most Evil Secret Societies in History (22 page)

Read The Most Evil Secret Societies in History Online

Authors: Shelley Klein

This resistance was further strengthened by the British who, on the advice of a senior member of the army, now decided to provide the Home Guard with firearms â a move they had previously dismissed, fearing the Mau Mau would try to appropriate the weapons.

But the British had a long way to go before any of their military operations bore fruit, for despite an increase in the number of soldiers being deployed to Kenya, and despite the rapid growth within the ranks of the Home Guard, tracking the Mau Mau down was an almost impossible task. The British administration's biggest break didn't come until early in 1954 when Waruhiu Itote (better known by the nickname âGeneral China'), one of the Mau Mau's most powerful leaders, was wounded during a minor skirmish with government troops and subsequently captured. While he was in custody, the police's Special Branch unit questioned Itote for days, trying to elicit from him not only information, but also an agreement that in return for his freedom he would attempt to negotiate a mass surrender of those men directly under his command. Before long, General Kaleba and General Tanganyika, both Mau Mau leaders like Itote, were also captured and âpersuaded' to participate in a negotiated surrender of their men. On March 30, 1954 members of the police, the army and the government sat down with a selection of Mau Mau representatives to thrash out a deal. The government guaranteed that all those who gave up their arms would not be executed, although inevitably their leaders would face long jail sentences. Furthermore, all those Mau Mau who weren't thought to have been actively involved in terrorist activities would be gradually rehabilitated into the community. It was a good deal, one which the British administration gave the Mau Mau ten days to consider. In the interim, however, another Mau Mau general called Gatamuki, who was adamantly against surrender of any description, kidnapped several of those who had attended the government negotiations. Government forces now had to move very swiftly to address what was rapidly turning into a major crisis. Manoeuvring their troops into position they mounted a full-scale attack on Gatamuki and his men, killing twenty-five Mau Mau and capturing nine others, including Gatamuki himself.

Placed under arrest, Gatamuki announced that, having spoken at length with the Mau Mau he had kidnapped, these men had persuaded him that surrender was the best option considering how low morale was within the Mau Mau's ranks. Conditions in the forests, where most of them were hiding out, had become intolerable. Food supplies were low, as were ammunition supplies, while the increasing strength of the government forces had left the Mau Mau's communications system in disarray.

Meanwhile, back in Nairobi, operations were under way to settle the Mau Mau question once and for all. Knowing that large pockets of insurgents were both living and operating within the city itself, Operation Anvil swung into action. On April 24, 1954, British troops sealed all exits to the entire city, thus preventing anyone from entering or leaving Nairobi. Then police began a methodical house-to-house search of the city. All identification papers had to be produced, with anyone who was suspected of belonging to the Mau Mau was arrested and sent to a detention center at Langata, five miles from Nairobi where they underwent further investigation. Similar screening operations were also carried out in the reserves, as were large-scale military sweeps through the Aberdare Mountain Range, where it was known that large numbers of Mau Mau operatives were still hiding out. Naturally, given that the enemy was well-practiced in guerrilla warfare, there were as many steps back as there were forward, but slow progress was made until finally, with the deployment of small tactical units made up entirely of Home Guard officers who knew the terrain better than anyone, arrests started to mount up.

Former Mau Mau leader Jomo Kenyatta became Kenya's first black Prime Minister in May 1963 and is pictured here (right) with Ugandan Prime Minister Milton Obote at a meeting in Nairobi the following month.

By the autumn of 1956, it was believed that there were only around 500 Mau Mau members still at large. The administration's main concern now was to track down and capture the last major player in the Mau Mau organization, a commander by the name of Dedan Kimathi, who was thought still to be hiding out in the Aberdare Mountains.

On October 17, 1956, Kimathi was wounded by Henderson's [Superintendent Ian Henderson, who conducted operations against the Mau Mau] men, but succeeded in escaping through the forest, but after traveling non-stop for just under twenty-eight hours and covering nearly eighty miles, he collapsed near the forest fringe. There he remained for three days, hiding in the day time, foraging for food at night. Early on the 21st he was found and challenged by a tribal policeman who fired three times at him, hitting him with the third shot. He was then captured, in his leopardskin coat, and in due course brought to trial and sentenced to death.

9

Indeed, it seemed only fitting that it was an African who brought down one of the last of the Mau Mau, for despite being a group who were ostensibly fighting for African rights, during their operations it was their fellow Africans who bore the brunt of the violence. The statistics agree; for it has been calculated that during the whole State of Emergency while 32 Europeans were killed and 26 wounded, a total of 1,817 African civilians died, with 910 wounded.

The general State of Emergency was finally lifted in December 1960 and shortly thereafter Jomo Kenyatta was released from prison. While he had been in jail, the newly-formed Kenyan African National Union (KANU) party had voted him their president, and on his release he was also admitted onto Kenya's Legislative Council.

In May 1963 Kenyatta became Kenya's first black prime minister, and led the country to full independence on 13 December of the same year.

Some strange malaise, some bitter aftertaste lingers on. We crane our necks and look around, as if to ask: where did all that come from? ⦠We will get nowhere as long as [we] continue to disown the Aum phenomenon as something completely other, an alien presence viewed through binoculars on the far shore.

H

ARUKI

M

URAKAMI

, from an article in the

Guardian

by Richard Lloyd Parry, March 18, 2005

T

he morning of March 20, 1995 began much like any other morning of any other day in Tokyo, Japan. People all over the city were rising, having breakfast, then heading off to the subway to get to work. But, unlike any other day, packages had been placed on five different trains; packages which contained plastic bags filled with a lethal chemical agent. Once laid on the floor each parcel was punctured by an umbrella tip, which allowed the chemical inside â a lethal nerve gas called sarin â to be released. It then spread throughout the carriages. What Tokyo was experiencing was a co-ordinated terrorist attack, one that was carried out by a sinister, secretive cult named Aum Shinrikyo. In fact, this was a double tragedy for Japan, for only nine weeks earlier the city of Kobe had suffered a massive earthquake in which 6,000 people died. The Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami described the two events like, âthe back and front of one massive explosion ⦠these twin catastrophes will remain embedded in our psyche as two milestones in our life as a people.'

1

The sarin-gas attack not only brought about a serious inquiry into the very heart of the Japanese state, it also spelt the beginning of the type of global terrorism best illustrated by the events of September 11, 2001, when two aeroplanes were deliberately flown into the Twin Towers in New York. But who was behind the events in Japan, in which thousands of people were injured and twelve people died? And what was the motive for causing havoc on such a large scale?

The self-proclaimed leader of Aum Shinrikyo was a man who called himself Shoko Asahara, although this wasn't his real name. His actual name was Chizuo Matsumoto, and he was born in the provincial city of Kumamoto on March 2, 1955 to impoverished parents, his father earning a living as a tatami-mat maker. Matsumoto was partially blind from birth, a disability which meant he was sent to a special government-run boarding school for the blind. Unlike the other children, however, he could see out of one eye, and it is said Matsumoto took advantage of this situation to bully and manipulate the other children into doing his bidding. Money was his main motivation; he rarely, if ever, helped out his blind schoolmates without first extracting payment from them. Not everything went his way though, for several times he tried to become president of the student body, but was unsuccessful on each occasion due to his lack of popularity.

Upon graduating, the young Matsumoto spent several years trying to gain entrance to Tokyo University. To attend this establishment was almost a pre-requisite for anyone wishing to enter Japan's governing elite, an ambition that Matsumoto had harbored since he was a child. Whether through bad luck or lack of application, Matsumoto failed to realize his dream â a setback that played bitterly on the young man's mind. Returning to his home town of Kumamoto, he took up a job in a massage parlor. It was hardly an auspicious beginning for an ambitious youngster, but at the age of twenty-three, determined to better himself, he returned to Tokyo. Here he set up the Matsumoto acupuncture clinic and married a nineteen-year-old college student called Tomoko, with whom he was to have six children. Shortly after setting up business in Tokyo, however, Matsumoto was arrested for the first time, for attempting to sell fake remedies to an unsuspecting public. He had apparently concocted a potion out of orange peel soaked in alcohol, that he called âAlmighty Medicine' and which he claimed was a traditional Chinese remedy for treating all types of illness. Together with a three-month course of acupuncture and yoga, Almighty Medicine was sold for $7,000 a pop.

After his arrest and a fine of $1,000, Matsumoto decided, during the 1980s, to travel to India, where he was inspired to take further yoga classes. He became fascinated by the idea of spiritual enlightenment, which certain types of yoga and meditation are said to promote. Suddenly Matsumoto knew what he wanted to do; he would return to Japan, set up his own yoga center, and encourage members not only to study a new type of faith, but also to regard him as this new faith's spiritual leader.

By 1987, Matsumoto's ambitions were realized; he named his group Aum Shinrikyo Matsumoto and it was at this time that he adopted the name Shoku Asahara. Initiates to the cult claimed that their leader had taught them not only spiritual enlightenment based on an eclectic mix of Buddhism, Hinduism, Shamanism, the writings of Nostradamus, apocalyptic Christianity and New Age beliefs, but also supernatural powers such as how to levitate and the art of telepathy. To most people these claims might seem ludicrous, but, disturbingly, within two years of its conception in 1989, Aum Shinrikyo had so many converts that the Japanese government was forced to grant it legal status as a religion (a move which also granted Asahara huge tax concessions). Indeed, at the height of Aum Shinrikyo's powers, in the mid-1990s, membership in Japan swelled to well over 10,000, with over 30,000 admirers and followers around the world, including a large group in Russia.

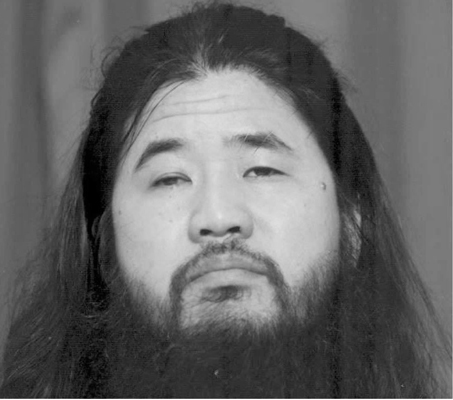

Shoko Asahara, a partially sighted academic failure and con artist, established a legal religion with himself as its head. He sold his beard clippings and bath water to followers, telling them they had curative or magic powers.

As the cult grew, so Asahara became increasingly confident. Anything he said was taken as truth. His followers didn't balk even when it came to some of the more bizarre rituals, such as the drinking of Asahara's blood, which they were informed had magical properties. At other times followers were encouraged to buy Asahara's bath water â which was also said to have miraculous powers. Clippings from Asahara's beard were sold with instructions to boil them in water and afterwards ingest the solution. Anything Asahara said was believed. There appeared to be no stopping either the cult or its leader â and naturally with such great power, also came great wealth. In March, 1995, one of Aum Shinrikyo's leading members estimated the cult's net worth as being in the region of $1.5 billion.