The Most Evil Secret Societies in History (25 page)

Read The Most Evil Secret Societies in History Online

Authors: Shelley Klein

The famous Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal stated that he only heard about Odessa during the Nuremberg trials, yet ever after was convinced of its reality, while other scholars have remained more sceptical. Few have done more to raise public awareness of the Odessa legend than the aforementioned novelist, Frederick Forsyth. His book, which was first published in 1972, tells the story of a group of former SS officers banding together to form an escape route out of Germany for high-ranking Nazis, with the aim of rebuilding their organization and thereafter establishing a Fourth Reich in order to fulfill Hitler's unrealized dreams. But for all that Forsyth's book is an engrossing read, and that the plot involves some genuine historical facts, ultimately the novel is only fiction. The truth, on the other hand, now that so many top-secret documents have been declassified and so many scholars have pored over the details, is probably stranger even than Forsyth's fiction. The real story involves an intimate collaboration of organizations as varied as the Catholic Church, the Argentine government (under president Juan Domingo Perón) and the Allied intelligence services.

As World War II began to draw to a close, it swiftly became apparent that large numbers of Nazi SS (who, due to the nature and magnitude of their war crimes, knew that surrender was not an option), together with those who were sympathetic to their cause, were fleeing Germany for sanctuary abroad in Spain, Portugal, Switzerland and Italy. The SS was the army within an army, devised by Adolf Hitler and commanded by Heinrich Himmler, which was charged with âspecial tasks' during the Nazi rule in Germany between 1933 to 1945. These âtasks' supposedly revolved around the promotion and protection of the Third Reich, but in reality were far more concerned with achieving Hitler's ultimate ambition, to rid first Germany and afterwards the rest of Europe of elements he considered undesirable. As a result, the SS executed in the region of fourteen million people â among them approximately six million Jews, five million Russians, two million Poles and a mix of gypsies, the mentally unstable, infirm and physically handicapped.

No wonder, then, that as the war drew to a close and Germany anticipated defeat, the men who had perpetrated or supported such inhuman acts knew that the civilized world would want retribution for their evil acts. They had no choice but to flee their homeland if they wanted to escape with their lives. For this they needed not only a support network made up of men and women sympathetic to their plight, but substantial amounts of money. To this end it is believed that on August 10, 1944 a secret meeting of top German industrialists (including steel magnate Fritz Thyssen, who bankrolled Hitler's rise to power in the 1930s) convened at the Maison Rouge hotel in Strasbourg. What they discussed has always remained secret, but the main outcome of the meeting was the establishment of a support network to aid and abet the escape of as many high-ranking Nazi officials as possible. Eminent figures such as Adolf Eichmann (head of the Jewish Office of the Gestapo), who was responsible for the murder of hundreds of thousands of Jewish men, women and children, felt the Allied net tightening and the need for escape paramount. Nor were his fears unfounded for, in the Soviet Union, war-crimes trials involving German officers responsible for the deaths of Jewish citizens had already begun. Taking the Russians' lead, the Western Allied forces also announced their intention of punishing all those involved in war crimes.

By April 1945, with the Red Army advancing on Berlin, many SS officers began creating the sort of fake documents they would need to flee the country under assumed identities. Neutral Spain was the initial destination of choice. French, Belgian and German Nazis or Nazi sympathizers turned up there in their droves, including Charles Lesca who would later become a key figure in the secretive Odessa organization.

Lesca had been born in Argentina, but had lived the greater part of his life in Europe, mixing with various key Nazis including the German Ambassador to Paris, Otto Abetz, as well as high-ranking Vichy officials. When he eventually fled Berlin for Madrid he settled at 4 Victor Hugo Street from where, after the electoral victory of Perón in 1946, it is believed Lesca began the systematic transportation of âall possible German intelligence officers to Argentina.'

1

But the first person to use Lesca's escape route was not a high-ranking Nazi official; instead, Carlos Reuter was a middle-aged banker who had recruited agents for the German intelligence service in occupied Paris. His journey began in late January 1946, taking him from Bilbao to Buenos Aires. The escape route was deemed a success and opened the gateway for many more fugitives, yet none of these âescapes' could have been possible without Argentina's backing or the full approval of President Juan Domingo Perón.

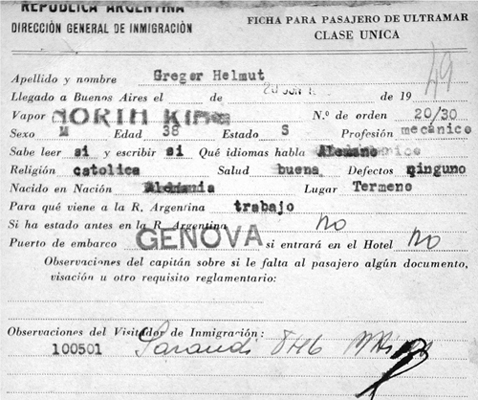

This Argentine immigration document from 1949, bears the name âHelmut Greger,' the alias adopted by the âAngel of Death' Dr. Joseph Mengele when Odessa helped him to flee from war-crimes trials in Europe.

Perón, as an ultra right-wing politician, had long been a supporter of Hitler and of the Nazi regime. With the aid of his military chiefs he had sought and established a secret alliance with Hitler in 1943, one that guaranteed mutual benefits. On Perón's side, Hitler allowed the Argentine military full access to the Nazi intelligence service's powerful communications network, thus enabling Argentina to spy on her neighbors. This was no small gift, but Perón also gave generously in return. He guaranteed Hitler indefinite freedom from arrest for all Nazi officials in Argentina. The deal was struck and a lifelong bond sealed, despite the fact that in January 1944 the Allies persuaded Argentina to break off all diplomatic ties with Germany. All was not, however, as it seemed, for even though Argentina went as far as to declare war on Germany one month before Hitler's suicide in Berlin in April 1945, the reality of the situation was that Perón only struck this pose to distract the Allies from the fact that he had begun setting up escape routes for Nazi fugitives. As he himself said:

[ â¦] if Argentina becomes a belligerent country, it has the right to enter Germany when the end arrives; this means that our planes and ships would be in a position to render a great service. At that point we had the commercial planes of the FAMA line [Argentine Merchant Air Fleet] and the ships we had bought from Italy during the war. This is how a great number of people were able to come to Argentina.

2

Another route by which âa great number of people were able' to escape to Argentina was via Perón's newly established DAIE (Delegation for Argentine Immigration in Europe) which he set up in Italy, with its main offices split between Rome and Genoa. Ostensibly, the organization was there to facilitate the emigration of Italians and other Europeans to Argentina, but covertly it was processing all the false documentation that was required by fleeing Nazis before they left Europe for South America. Although the DAIE was extremely efficient, prior to approaching it any prospective émigré also had to obtain a landing permit from the Argentine Immigration Office as well as a travel permit from the Red Cross. Acquiring a Red Cross permit using a false name was not as difficult as it might at first seem because the Red Cross documents were intended for refugees who had lost all other forms of identification. Armed with all of the above it was relatively straightforward for the unscrupulous Nazi fugitive to gain entry into his newly-adopted country. Without the offices of, among others, the Catholic Church both in Europe and in Argentina, however, Perón's plans would never have reached fruition.

One church official, Bishop Alois Hudal, wrote to President Perón on August 31, 1948 expressing the wish to obtain 5,000 visas for German and Austrian men, who were not refugees as such, but fighters who had made great sacrifices to save their country. Hudal was named by the Vatican as its special envoy to visit the German internees at the numerous âcivilian' camps dotted all over Italy, camps in which hundreds, if not thousands of Nazi officers were hiding among real refugees. Indeed, Hudal was later praised by several leading Nazi officers for his help during these years, including the Luftwaffe hero Hans-Ulrich Rudel, who wrote:

Rome became a sanctuary and salvation for many victims of persecution after the âliberation'. More than a few of our comrades found the path to freedom through Rome, because Rome is full of men of good will.

Nor was Hudal reticent about documenting his post-war efforts, for in his book

Roman Diary

he noted:

I felt duty bound after 1945 to devote my whole charitable work mainly to former National Socialists and Fascists, especially the so called âwar criminals'.

Joining him in these efforts were numerous other dignitaries of the Catholic Church, including Archbishop Giuseppe Siri of Genoa (one of the main points of departure from Italy to Argentina), who founded the National Committee for Emigration to Argentina. But perhaps the most shocking of all the Catholic Church's officials to help the Nazis was the Pope himself â Pius XII. For many years the Catholic Church denied any involvement of Pius in supporting Germany's war criminals, let alone his sanctioning of the Church's efforts to help them escape Italy. What cannot be ignored, however, is that between 1946 and 1952 Pius sent several pleas to those presiding over the Nuremberg war trials to commute the death sentences hanging over key Nazi officials.

Among the death sentences the Pope wished to see commuted were those of Arthur Greiser, convicted for the murder of 100,000 Jews in Poland; Otto Ohlendorf, who had murdered some 90,000 people as commander of the mobile killing squad Einsatzgruppe D; and Oswald Pohl, head of WHVA, the vast SS agency that ran the Nazi concentration camps, overseeing a slave force of 500,000 prisoners and supervising the conversion of victims' jewelry, hair and clothes to hard currency.

3

Sadly, the Pope and the Catholic Church weren't the only ones aiding and abetting the escape of Nazi officers. In his book on the subject, Uki Goni explains how the Swiss Federal Archives still hold records revealing that several prominent Swiss officials permitted 300 Nazi Germans to travel through Switzerland, no questions asked, on their way to Argentina.

Naturally, Perón also had his own agents in place, both in Europe and in Argentina. Two such were former SS Captain Carlos Fuldner and Rodolfo Freude, chief of the Perón government's secret service. Fuldner was born in Argentina in 1910 to German immigrant parents who, when Fuldner was eleven years old, returned to Germany with their children and set up home in Kassel. By the age of twenty-one, Fuldner had been admitted into Hitler's SS, where he was quickly promoted to the rank of captain. All was not as it seemed, however, for Fuldner had a penchant for high living, generally paid for with other people's money. According to several accounts from that period, he swindled not only a shipping company out of a sizable sum of money, but also the SS, as a consequence of which he decided to flee Germany and return to his homeland. His escape was not successful and having been captured, he was expelled from the SS and spent some months in jail. Despite this, Fuldner's career was not yet at an end, for at some point between being released from jail and the end of World War II, Fuldner's star rose once more when Heinrich Himmler employed him on a âspecial mission' to help set up a German/Argentine ratline to smuggle people such as Adolf Eichmann and the âAngel of Death', Josef Mengele, out of Germany. In this new role, Fuldner traveled extensively throughout Europe, often skipping between Spain, Italy and Germany within the space of a few days. Fuldner also played a key role running Perón's DAIE office in Genoa.

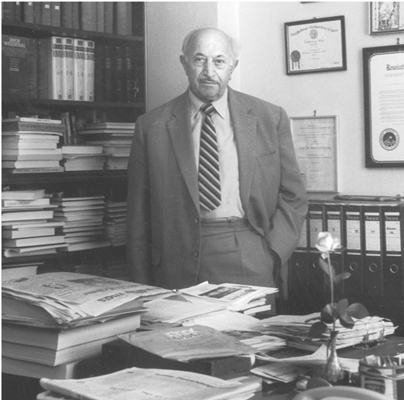

Although the existence of the Odessa network has been disputed, Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal (above) was convinced the secret organization had helped senior Nazis to escape justice from the moment he first heard mention of it at the Nuremberg Trials.

The second key member of Perón's team, Rodolfo Freude, was also of mixed German/Argentine origin although his father, Ludwig, far outranked Fuldner's father, being a close personal friend of Perón's as well as having proven Nazi credentials. With this background it is not surprising that Rodolfo Freude, as soon as he was of age, went to work for Perón. Nor is it surprising that when Perón was first elected president, Rudi (as he was known) became his spy chief.