The Most Evil Secret Societies in History (21 page)

Read The Most Evil Secret Societies in History Online

Authors: Shelley Klein

This is a Kikuyu secret society which is probably another manifestation of the suppressed Kikuyu Central Association. Its objects are anti-European and its intention is to dispossess Europeans of the White Highlands. Its members take an oath not to give information to the police, and may also swear not to obey certain orders of the Government. It is suspected that some members employed on European farms indulge in a âgo slow' policy and that they may also have committed minor acts of sabotage on farms. Successful prosecutions against the society are believed to have checked its growth; or at least to have curbed the forceful recruitment of adherents. The potency of the organization depends on the extent to which it possesses the power latent in all secret societies, of being more feared than the forces of law and order.

5

Despite the above recognition of the problem, and despite the Mau Mau having been declared illegal, during January 1952 reports continued to trickle through about âoathing ceremonies' not only in Kenya's northern territory, but also in the Nairobi district. It was a desperate state of affairs, yet the colonial Governor at that time, Sir Philip Mitchell, who was an acknowledged expert on African matters, didn't appear too concerned. Following the Internal Security Working Committee's report he glibly stated that Africans were nothing but a primitive people and, therefore, what could one expect them to do but dabble in black magic and oath-taking ceremonies? By February 1952, events had become even more grave, with several reports of crops being set alight on land belonging to the white settlers. But the attacks were not only restricted to the white-owned coffee plantations â there were additional reports of Mau Mau violence in Nairobi's white suburbs. In May 1952 intelligence reports suggested that the content of the Mau Mau's oaths had begun to change character â moving away from a general promise to commit violence against European settlers in favor of more specific threats of murder against named individuals. The practice of oath-taking was also being seen on a larger and larger scale, with massive initiation ceremonies taking place involving up to 800 people. Those Kikuyu who would not take the oath, or informed on those that did, were summarily killed and mutilated.

On September 25, 1952, five white-owned farms were attacked. Outbuildings were burnt to the ground and over 400 sheep and cattle were either maimed or killed. With all this going on, it might be expected that Governor Mitchell would change tactics, instead of which he continued to dismiss claims that any major problem existed in Kenya. It wasn't until his departure from the country (on authorized terminal leave) that any serious effort was made to combat the Mau Mau.

The new Governor was a man by the name of Sir Evelyn Baring who, on arriving in Kenya, immediately conducted a week-long tour of the colony. He was made aware that the Mau Mau had murdered in the region of forty people in the past month alone, and were also beginning to acquire large quantities of firearms. Baring swiftly concluded that the only remedy to the situation would be to declare a full-scale State of Emergency accompanied by an increase in the number of British Army personnel in Kenya.

In a letter addressed to the Secretary of State for the Colonies Baring wrote:

I have just returned from a tour [of Kenya] and the position is now abundantly clear that we are facing a planned revolutionary movement. If the movement cannot be stopped, there will be an administrative breakdown followed by bloodshed amounting to civil war.

6

On October 21, a State of Emergency was finally declared and troops began pouring into the country. Anyone suspected of being a political agitator was rounded up, including Jomo Kenyatta, president of the KAU, who was now accused of belonging to the Mau Mau. It is a generally accepted view among modern researchers and historians that the militant branch of the KAU was linked to the Mau Mau, and it is also agreed that the Nairobi criminal underworld comprised of a high percentage of Mau Mau operatives as well. What has never been proved satisfactorily, however, is Kenyatta's link to this secretive and extremely violent organization. After all, his modus operandi was always to present himself as a rational African leader through whom the British could reach a satisfactory resolution with the Kenyan people.

Following the declaration of the State of Emergency, events moved swiftly with the Kenyan government making every effort to suppress the Mau Mau and protect its white citizens. Kenyatta was flown to Kapenquria, where he was placed under heavy armed guard to await trial (in 1953 he was sentenced to seven years' imprisonment with hard labor), while approximately 112 others were also arrested on suspicion of Mau Mau involvement. On the morning of October 22, Nairobi's citizens were alarmed to find the Lancashire Fusiliers patrolling their streets, and the next day the Royal Navy cruiser

Kenya

arrived in Mombassa carrying a detachment of Royal Marines, who were deployed to suppress any Mau Mau activity in that city as well.

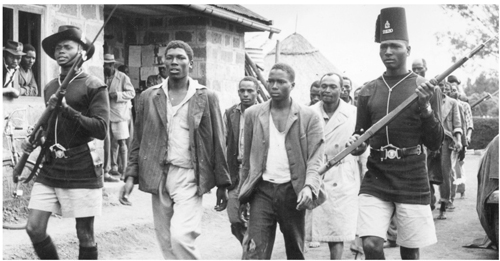

Guards escort Mau Mau suspects to cells in Nairobi in November 1952. The month before, the Mau Mau problem had become so acute that a State of Emergency was declared and British troops were deployed in Kenya.

Yet, despite the mass arrests in Nairobi and the surrounding areas, it soon became apparent that the Mau Mau were still growing in strength. A Kikuyu chief who was sympathetic towards the British administration's goals attempted to break up a Mau Mau oathing ceremony, only to be hacked to pieces with machetes by the crowd. Shortly afterwards the Mau Mau claimed their first white victim, a farmer by the name of Eric Bowyer. Bowyer lived with two African servants on an isolated holding. While he was taking a bath, Mau Mau rebels broke into the house and slaughtered all three

occupants. Acts such as this continued apace, leaving the colonial administration feeling frustrated and impotent. Their problems appeared to be threefold. Firstly, there was an acute lack of reliable intelligence to indicate the Mau Mau's organizational structure, how well it was armed and what its intentions were. This meant that government forces were unable to plan an appropriate strategy to overcome the rebels. Secondly, the armed forces operating in Kenya were of very mixed abilities. There was the British military, the colonial military, a critically understaffed civilian police force and an unarmed tribal police unit. Finally, all of the above units operated independently from each other, with very little organized coordination.

To resolve some of these problems it was decided that Kenya's only intelligence agency (a Special Branch unit of the Kenyan police) would be upgraded and trained specifically to combat the Mau Mau. The Lancashire Fusiliers were deployed up-country to the Rift Valley province around Thomson's Falls, Naivasha and Nakuru, which had all been designated Mau Mau trouble spots, while the King's African Rifles were deployed mainly in the native reserves of the Central province as well as around Nairobi. The colonial administration also saw to it that those Kikuyu who were loyal to the British were allowed to form a self-defence unit known as the Home Guard. Slow headway was being made by the British administration, but it was always set against a background of continuing Mau Mau activity.

Charles Hamilton Ferguson lived on a remote farm in the Thomson's Falls area of Kenya when, on January 1, 1953, while enjoying a late dinner with a friend, Richard Bingley, a gang of Mau Mau insurgents swept into the house and murdered the two men where they sat. The next evening, the Mau Mau attacked another farmhouse, this time located near Nyeri. This house was owned by a Mrs. Kitty Hesselberger and her companion Mrs. Raynes Simpson. Mrs. Simpson, according to a later police report on the incident, was seated in the living room of the house with her face to the door, and on the arm of the chair she was sitting in she had placed a gun. When the houseboy entered, Mrs. Simpson, noticing something odd about his appearance, swiftly picked up her weapon and was immediately confronted by a gang of Mau Mau thugs piling into the room. Her first shot mortally wounded the gang's leader while it is believed her second shot distracted another Mau Mau member who was about to kill Mrs. Hesselberger. Mrs. Simpson then continued to fire her weapon, giving Mrs. Hesselberger the opportunity to pick up a shotgun, at the sight of which the remaining Mau Mau fled.

Other victims of Mau Mau attacks were not so fortunate. Over the following two weeks, it is believed that thirty-four Africans were murdered by the Mau Mau, yet it wasn't until the events of January 24, 1953 that the world became fully aware of the type of atrocities the Mau Mau were prepared to commit in the name of freedom. On that night, at a remote farm owned by a Mr. Ruck, a gang of Mau Mau were smuggled onto the premises by Mr. Ruck's African employees. At 9.00 p.m., while Mr. Ruck was having dinner with his wife, he was asked by one of his servants to step outside as they had caught an intruder on the premises. Mr. Ruck did as he was requested, only to be struck down as he exited the house. On hearing his cries for help, his wife grabbed a gun, but was quickly overcome by the insurgents before she could fire a shot. Both bodies were later found outside in the scrubland, where they had been badly mutilated. But as if that wasn't sickening enough, the Mau Mau conducted a thorough search of the house, during which they came across the Ruck's six-year-old son, Michael, asleep in bed. What was done to this little boy does not bear description.

However horrific these single incidents were, two months later on March 26, the Mau Mau stepped up their programme of terror and instigated two large-scale operations. The first targetted Naivasha police station â a change from previous operations, which normally concentrated on isolated farms. Just after midnight on March 24, approximately eighty-five Mau Mau, having shot the watchtower sentry, broke through the station's outer perimeter of barbed wire. They then split into two groups. The first group headed for the police station's main office, where they killed the duty clerk, while the second group headed straight for the station armory where they stole as many weapons and as much ammunition as they could carry. Having driven a truck into the compound, the armory raiders loaded it with their newly acquired arsenal while the other group breached the walls of a nearby detention center, releasing 173 prisoners. Naturally, during all this mayhem several gunshots were fired, awakening all those off-duty officers who were asleep in their barracks. Luckily for them, on realizing the nature of the attack they fled to safety rather than face up to the Mau Mau, who by this time were making away with their arms haul.

While the Naivasha raid was in full swing, another Mau Mau unit was gathering around the settlement of Lari, located approximately thirty miles south-southeast of Naivasha. Lari was home to many hundreds of Kikuyu men, women and children, most of whom were opposed to the Mau Mau or, worse still, were members of the Kikuyu Home Guard. Lari was also a base for the King's African Rifles, but on the night of the 26th most of the soldiers had been sent to the Athi River Prison, where it was feared a mass break-out was planned.

With its defences down, Lari made an easy target for the Mau Mau. An estimated 1,000 insurgents, split into a number of groups, spread themselves throughout the village so that they could attack the homesteads simultaneously. Each unit had a specific task, with one group ensuring that all the huts were bound with cable around the outside to prevent the doors from opening. Another unit then soaked the huts with petrol while a third squad was tasked with attacking all those trying to escape the ensuing fires. Over 200 huts were burned to the ground during the attack at Lari. Thirty-one people are believed to have survived, but nearly all of these suffered horrendous injuries. Because a large percentage of Lari's male population was out on patrol on the night in question, most of the dead were women and children. It has also been estimated that over 1,000 cattle were slaughtered during the raid.

Worldwide reactions of horror over both the Naivasha and Lari attacks bolstered the British administration's resolve to wipe out the Mau Mau. More reinforcements were required so that the military could get on with the job. In addition, the police, the army and all the various civilian loyalist groups also began working more closely together and began conducting large-scale raids through areas that were thought to be Mau Mau strongholds.

6000 Africans in the shanty village of Kariobangi (near Nairobi) were rounded up for questioning April 24 and their village was ordered destroyed by bulldozers. 7000 natives in two villages northeast of Nairobi were evicted April 17 and their homes were leveled similarly April 19. The area was called Nairobi's Mau Mau headquarters.

7

The administration also instigated what became known as the Kikuyu Registration Ordnance Act, which in effect meant that any Kikuyu living outside a designated reserve had to carry identification papers. But nothing was as easy as it seemed, for when the Mau Mau heard of this new initiative they âpersuaded' most of the Kikuyu to resist this order by returning to the reserves. The majority of white farmers, now more than ever before fearing Mau Mau attacks, dismissed their black servants and land workers who, having nowhere else to live, also returned to the reserves. Suddenly, tens of thousands of people were converging on land meant to house a fraction of that number, a situation which in turn led to overcrowding and bitter resentment among the largely Kikuyu population. The Mau Mau took full advantage of this disaffection, recruiting new members by the dozen. Yet, despite this sudden eagerness of Kikuyu to join the Mau Mau, there were still a fair number unwilling to sign up to such an organization â particularly given that the massacre at Lari, far from targeting white landowners, instead involved the murder of their fellow countrymen. Indeed, by mid-1953 the biggest question on the minds of most Kikuyu tribesmen was whether to join an organization which actively promoted the brutal and often irrational murder of their own kind, or to take a stand against them. Many chose the latter option, joining the British administration's Home Guard. âWhatever use the Government made in publicizing the Lari Massacre to the world,' wrote A. Marshall McPhee in his account of this time, âthe fact remains that it was the turning point against the Mau Mau; many more rallied to the Kikuyu Guard and from this time on Mau Mau would meet increasing resistance from the people they sought to liberate.'

8