The Most Evil Secret Societies in History (20 page)

Read The Most Evil Secret Societies in History Online

Authors: Shelley Klein

Lacking the manpower and weaponry to wage all-out war, the Hashishim were not, as is often assumed, any real threat to the Crusaders, unlike the Saracen warriors depicted in this illustration from the thirteenth-century French manuscript

Chroniques de Saint-Denis.

But perhaps the most significant point to be made about these, the earliest of terrorists, is that they failed utterly in their dream of overthrowing the existing order. For decades they caused ripples of fear throughout the regions they targeted, but Chroniques de Saint-Denis. ultimately they did not succeed in gaining control of even one major city. They possessed several significant castles and the land thereabouts, but in reality these were no more than âpetty principalities'.

Although the Ismailis eventually faded away, the same cannot be said for the manner in which they operated. History has proved only too well that their revolutionary tactics have trickled down through the centuries, finding countless converts along the way. One only has to look towards the Middle East and the suicide bombings that occur there, or to the Twin Towers attack in New York on September 11, 2001, to notice the striking resemblance between those terrorist activities committed in medieval times and those committed today. The absolute secrecy of the terrorist cell, the complete dedication of the assassin to his cause in return for guaranteed entry into Paradise, the calculated implementation of terror â the parallels are numerous. The medieval Assassins and terrorists operating today do, however, show one marked difference. Whereas Hasan-i Sabbah and his successors targeted the leaders of the existing order â that is to say Sunni generals, ministers, monarchs and religious functionaries â they went to great lengths not to involve or harm any civilians. Their counterparts today appear not to care whom they kill, be they men, women or children, Christian, Muslim or Jew, black or white.

There is one last parallel that might still be drawn between the two groups. It could be argued that Osama bin Laden, the world's most wanted terrorist is, in a very real way, our present-day Old Man of the Mountain. After all, who can forget the video footage of bin Laden addressing (and threatening) the world from his mountain hideaway somewhere in Afghanistan? Let us hope that, like Hasan-i Sabbah, he fails to realize his dreams.

The settler knew a lot about how to use African labor. But he could not see what the use of that labor and the production of money was beginning to bring about. He could not see the political change.

W

ILLOUGHBY

S

MITH

, District Officer in the Colonial Service, 1948-55

T

o understand the nature of the Mau Mau and of the Mau Mau uprising, it is first necessary to understand a little of the history of Kenya and in particular of the British Colonial administration from approximately the mid-nineteenth century until 1963.

The first Europeans to penetrate East Africa are thought to have been British and German missionaries who, as well as bringing the word of God and so-called Western civilization to the natives, also brought an attitude of acute moral outrage, particularly over the type of heathen practices in which, in their opinion, the natives were prone to indulge. For instance, a large number of the indigenous population did not wear clothes and their nakedness shocked and offended the Europeans, as did the custom of placing their dead in animal traps so as to entice prey to eat. For all their efforts, however, the missionaries made little headway in Kenya. It wasn't until around 1880 that the British Imperial East Africa Company began to prospect in the region, looking for suitable land that could either be farmed or mined, or better still, both. At this point the Germans had an established protectorate over the Sultan of Zanzibar's coastal regions, but in the 1890s Germany handed these holdings over to the British who subsequently, in 1895, established the area as a British settlement under the name of the East African Protectorate. Slowly but surely, the British brought the southern half of Kenya under their control too, although the northern half didn't truly come under British rule until well after World War I (1914-18), during which time both British and South African settlers moved in to the highland regions of the country (soon to be nicknamed the White Highlands). This area contained rich farming land together with a climate perfectly suited to the business of growing coffee. The only drawback was that most of the territory belonged to Kenya's Kikuyu tribe â a fact the British neither appreciated nor cared to acknowledge. The Kikuya were driven out of their homes and effectively excluded from owning their own land. As if this were not humiliation enough, the Kikuya also suffered when the European settlers decided they required ever increasing amounts of cheap labor in order to run their businesses efficiently. They persuaded the administration to raise taxes on their African neighbors so that increasing numbers of black Kenyans would either be forced to seek work on the farms in order to pay off their tax debts, or to find employment in urban areas such as Nairobi.

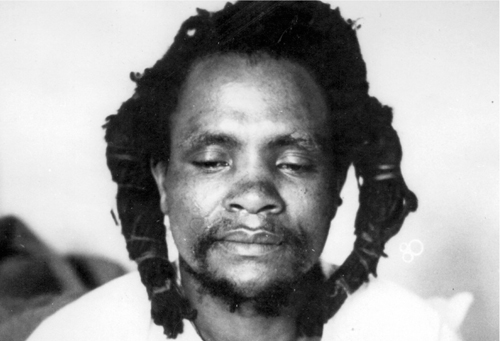

Dedan Kimathi was the last of the Mau Mau leaders to be brought to justice. Shot and captured by a Kenyan police officer in October 1956, he was tried and executed for his crimes.

In 1920, Kenya was named a British Crown colony and Sir Charles Eliot was appointed Governor, with an elected Legislative Council to provide him with both advice and support. Naturally, given Britain's dismal colonial record, native Kenyans were not allowed on this committee; it would not be until the 1940s that a small number would, begrudgingly, be given seats. Eliot, who was first and foremost a scholar of languages (he had published several books, including one on Finnish grammar and another on the Ottoman Empire), was an inflexible man of the old school who believed that Kenya was a âwhite man's country in which the interests of the European must always be paramount.'

1

This attitude was commonplace during the period â based as it was upon the earlier Victorian conviction that it was the white man's duty to civilize his African cousins. This was the proverbial âwhite man's burden': to civilize the Africans and teach them to know their place and accept it.

Given the extent to which the native Kenyans were subjugated and brow-beaten by the British, it is hardly surprising that resentment grew not only at their gross mistreatment but also due to the lack of proper representation in government. Not long after World War I, a political party, made up solely of Kenyan Africans, mobilized themselves into an opposition movement protesting against the government's crippling tax system, as well as the general lack of opportunities for black Kenyans, the colonial labor-control policies and, most important of all, the illegal appropriation of land, which by 1948 saw approximately 1.25 million Kikuyu restricted to 5,200 square kilometers of scrubland. This was in sharp contrast to the 30,000 European and South African settlers, who enjoyed 31,000 square kilometers of the most desirable farmland.

One of the first of these opposition groups was called the East African Association, but the British swiftly outlawed this organization in 1922. In 1924 a second group was formed called the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA), which demanded not only that the British return all farmlands previously stolen from the Kikuyu to their rightful owners, but that they respect the Kikuyu culture and Kikuyu society. This group, however, much like its predecessor, failed to make any significant headway. Then, in 1945, following the end of World War II , opposition to British rule became increasingly nationalistic and far more noticeably vociferous. This was undoubtedly partly due to the fact that many Africans had been conscripted to help fight alongside the British during the war, and as a result their political consciousness had been raised to the extent that when they returned to civilian life they were no longer prepared to live as second-class citizens in their own country. In 1944 a new political organization had been formed â the Kenyan African Union (KAU). The main leader of this party was a Kikuyu by the name of Jomo Kenyatta who had previously belonged to the KCA. Kenyatta was determined to address the problems of his native Africans and improve their lot but, much as with the KCA, when it came to challenging British colonial rule, the KAU had made little progress.

It was at this point, during these turbulent post-war years that a secret Kikuyu guerrilla organization called the Mau Mau first came into being.

Mau mau

is, experts on African languages assert, a term of uncertain provenance. Some people claim it is the Kikuyu word for a group of hills bordering the Rift Valley and Lake Naivasha in northern Kenya, while others maintain the word is a rough alliteration of the Kikuyu war cry. A third interpretation has it that Mau Mau is a British invention meant not only to denigrate the insurgents, but to demonize them. In a British television Channel 4 documentary,

How Britain Crushed the Mau Mau Rebellion

, the historian Professor Lonsdale remarked how the Mau Mau were first portrayed by the British government as âthe welling up of the old unreconstructed Africa, which had not yet received sufficient colonial enlightenment and discipline, which proved that colonialism still had a job to do.' In other words, the Mau Mau were little more than savages bent on misrule and destruction.

Whatever the provenance of the word Mau Mau â be it a form of demonization or the Kikuyu war cry â it is believed that the group was first established some time between 1947 and 1952 with one aim in mind: to free Kenya from colonialism at any cost. In practice, this involved the Mau Mau in a campaign of anti-colonial terrorist violence in which large numbers of both Europeans and Africans were killed.

There had always been a minority of native Kenyans who had cooperated with, and therefore benefited from, colonial rule. Targeting these groups (who mainly lived and worked in the Nyeri District of the Central Province) was relatively easy, and many black âcollaborators' subsequently died. Yet the Mau Mau's violence was, at least initially, directed against the white settlers â a violence that was reflected in the group's wild initiation ceremonies. These ceremonies made extensive use of ancient symbols and black magic together with the number seven which, for the Kikuya, has huge significance as it is directly linked to their most sacred initiation rites.

Writing extensively about such initiation ceremonies in his book on the Mau Mau, and basing much of his work on the writer L.S.B. Leakey's original research, Fred Majdalany describes one such ritual:

It is quite dark and he [the initiate] is ordered to remove his clothes. In the darkness he is pushed forward and receives his first Shock when his naked body is brushed by the outline of an arch. This is totally unexpected, but he knows it is the arch of sugar cane and banana leaves through which he has to pass during his initiation into manhood [â¦] Now they would go to work on him quickly. He would be ordered to eat a piece of sacrificial flesh thrust against his lips. This would be done seven times and after each he would have to repeat the oath. Then the lips would be touched with blood seven times, the oath being repeated after each. Next a gourd of blood would be passed round his head seven times; he would be ordered to stick seven thorns into a sodom apple and pierce the eye of the sheep.

2

This blend of both the sacred and the profane had a lasting effect on the initiates, who would usually be totally overcome by the ceremony. âWe used to drink the oath,' one ex-Mau Mau insurgent, Jacob Njangi, admitted. âWe swore we would not let white men rule us for ever. We would fight them even down to our last man, so that man could live in freedom.'

3

Majdalany also listed the set of oaths he believed Mau Mau initiates were required to take:

(a)

â

If I ever reveal the secrets of this organization, may this oath kill me.

(b)

â

If I ever sell or dispose of any Kikuyu land to a foreigner, may this oath kill me.

(c)

â

If I ever fail to follow our great leader, Kenyatta, may this oath kill me.

(d)

â

If I ever inform against any member of this organization or against any member who steals from the European, may this oath kill me.

(e)

â

If I ever fail to pay the fees of this organization, may this oath kill me.

4

The deaths that ensued from failure to adhere to such oaths were savage in the extreme. Many of the corpses of former Mau Mau that were discovered had wounds that were characteristic of the ritual mutilation favored by the Kikuyu. Despite the bloodshed, however, or perhaps because of it, more and more people joined the Mau Mau until, in 1950, having enjoyed unimpeded growth, the organization was declared illegal. In August of that year Kenya's Internal Security Working Committee had been tasked with evaluating the insurgency question. Its report was a corrosive denunciation of the Mau Mau, which was defined as follows: