The Most Evil Secret Societies in History (12 page)

Read The Most Evil Secret Societies in History Online

Authors: Shelley Klein

Excerpt from Triad Society Initiation Ceremony:

Incense Master: As a vanguard are you versed in civil and military matters?

Vanguard: I am well versed in both.

[ â¦]

Incense Master: Name the eighteen kinds of military arts you learned at Shao Lin.

Vanguard: First I learned the use of the rattan shield.

Second the use of metal darts.

Third the use of the trident.

Fourth the use of the metal rod.

Fifth the use of the spear.

Sixth the use of the wooden staff.

Seventh the use of the sword.

Eighth the use of the halberd.

Ninth the use of the fighting chain.

Tenth the use of the iron mace.

Eleventh the use of the walking stick.

Twelfth the use of the caltrops.

Thirteenth the use of the golden barrier.

Fourteenth the use of the double sword.

Fifteenth the use of the duck-billed spear.

Sixteenth the use of the tsoi yeung sword.

Seventeenth the use of the bow and arrow.

Eighteenth the use of the lance.

4

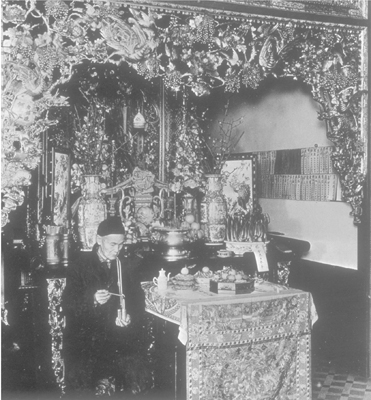

Elaborate carvings and ornamentation decorate this centerpiece of the headquarters of the Hop Sing Tong in San Francisco's Chinatown in 1929.

Given the nature of the above, it is hardly surprising that both the Tongs' and the Triads' feuding, particularly amongst their own kind, was particularly bloodthirsty. In New York the first Tong wars were said to have broken out around 1900, only a little later than those on the west coast of America. New York, in fact, suffered from prolonged bouts of internecine warfare among various Tong factions, in particular between the Hip Sing Tong and the On Leong Tong.

The On Leong Tong, whose leader at that time was a man by the name of Tom Lee, for the most part controlled the so-called âproperty rights' system, which meant that they made their money from the lucrative gambling and opium dens in New York's Chinatown. In contrast, the Hip Sing Tong's power lay in the number of criminal associates that were attached to its ranks and the diversity of their activities. For approximately a decade, the two Tongs operated without significant rivalry between them, but when the Hip Sing Tong (whose leader was called Mock Duck) attempted to usurp its rival and take over some of the On Leong Tong's property rights, fighting broke out. Mock Duck arranged for his men to attack On Leong members in a downtown Chinese theater. The result was a massacre the like of which had rarely been seen in New York before. Several further acts of violence occurred and an increased police presence became required â something neither Tong was happy about. Indeed, so uncomfortable were the Chinese with an âoutside' police presence on their territory that eventually both Tongs sat down at a negotiating table and reached an agreement. Not that this was the end of Tong rivalry in New York. During the 1920s and 30s several more wars broke out â one of which hit the headlines as follows:

Two shots were fired in the poolroom. About forty billiard cues clashed on the floor, as the young Chinese, who had been gathered around ten tables, dashed in a panic for the doors. In about a second the place was empty of pool-shooters and employees. In another second it was filled up with curiosity-seekers, mostly Americans and Italians, and policemen.

There was a swarm of policemen on the scene before the smoke had cleared away, because about twenty had been posted by Inspector Bolan at former gambling houses in Chinatown which he had closed up in recent weeks.

5

Naturally, none of the above outbreaks of violence endeared the Chinese to their white Americans cousins for, despite most of the immigrants being hard-working, law-abiding citizens, it was always going to be a case of the minority ruining things for the majority.

Soon white Americans were pressing for radical changes to be made so as to exclude the Chinese from mainstream American life. Under the terms of the 1898 Burlingame Treaty (named after Anson Burlingame who was the US minister to China during the Lincoln and Johnson administrations) both China and America had recognized âthe inherent and inalienable right of man to change his home and allegiance, and also the mutual advantage of the free migration and emigration of their citizens and subjects, respectively for purposes of curiosity, of trade, or as permanent residents [ â¦] Chinese subjects visiting or residing in the United States, shall enjoy the same privileges, immunities and exemptions in respect to travel or residence, as may there be enjoyed by the citizens or subjects of the most favored nation.'

6

In other words, the American government had initially been more than willing to provide the Chinese with laws that protected them against exploitation, violence and discrimination. After the Tong wars however, all this changed. The US Government came under increasing pressure to do something about the âChinese problem' and the Burlingame Treaty was replaced with the Chinese Exclusion Act of May 6, 1882.

This was the first major restriction on immigration that the United States had ever implemented and illustrates just how high feelings were running in regard to the Chinese in general and the Tongs in particular. The new Act stated:

Whereas in the opinion of the Government of the United States the coming of Chinese laborers to this country endangers the good order of certain localities within the territory thereof:

Therefore,

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That from and after the expiration of ninety days next after the passage of this act, and until the expiration of ten years next after the passage of this act, the coming of Chinese laborers to the United States be, and the same is hereby, suspended; and during such suspension it shall not be lawful for any Chinese laborer to come, or, having so come after the expiration of said ninety days, to remain within the United States.

7

After ten years the above law (renamed the Geary Law) was extended for a further decade, at the end of which it was then made permanent. Further to this, the Scott Act of October 1, 1888 also prevented any laborer of Chinese origin who had left the United States on a temporary basis i.e. to visit his family back in China, from returning to America. In this way almost 20,000 Chinese immigrants were refused re-entry into the country. In 1924 Chinese wives were also prevented from joining their husbands in their newly adopted country. It was the first and last time legislation such as this, involving the exclusion of a specifically-named nationality, was ever passed in America and in some ways it stands as testimony to the fear the Tongs had instilled into the heart of white America. The situation didn't really improve until World War II when the United States became allied to China in the fight against Japan.

Tong feuds cost many lives among the Chinese community in America and great efforts were made to maintain peace between rival factions, as at this conciliation meeting between the Hip Sings and Ping Koongs in San Francisco in 1921.

In 1943 the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed and 105 persons of Chinese origin were allowed into the United States per year, after which they could become naturalized American citizens. Further to this, after World War II more legislation was passed softening America's anti-Chinese stance â for instance the Displaced Persons Act of 1948 permitted approximately 3,500 persons of Chinese origin who were stranded on America's shores due to the political situation back in China, permanent refugee status. Following on from this, in 1953 the Refugee Relief Act was passed allowing hundreds more Chinese to settle in America and become legal citizens.

From the mid 1940s onwards, therefore, the Chinese population increased rapidly on American shores. Chinatowns were once again in abundance â enclaves where Chinese culture could be both protected and encouraged. Naturally this âculture' included not only the Chinese language, the study of Chinese history and the arts, the practice of Chinese medicine and the appreciation of Chinese food, but also the return to the old Chinese customs, which included the acceptance of the Tongs as a Chinese way of life.

Stronger than before, with more Chinese communities in which to operate, the Tongs grew and prospered. Extortion rackets proliferated. The Chinese â notoriously reticent at going to legitimate police agencies in order to report crime â made for rich pickings for the Tongs. Businessmen were only too eager to pay protection money, but, for the Tongs, the financial gains weren't the only reason behind their actions. The more shopkeepers and restaurateurs who belonged to a particular Tong, the stronger and more important that Tong became, with an even larger âturf' area or kingdom over which they could rule. Not all Tongs, however, used out-and-out violence to get what they wanted. One tried and tested method to squeeze money out of a reluctant restaurant owner involved a whole group of Tong members arriving at a restaurant, but sitting down at separate tables. Each person would then order only very little from the menu, but stretch out his or her meal for hours on end therefore blocking the tables so that no other customers could sit down and eat. This type of behavior could stretch on for days or weeks, considerably reducing a restaurant's takings and ruining the business. However, the moment the owner began paying protection money, the problem would melt away. The Tong achieved exactly what it desired without so much as a drop of blood being spilt.

A different method of squeezing extortion money out of a reluctant restaurateur was to post guards at the door of his establishment who would then warn customers away. Only a very rich businessman could afford to allow this type of practice to continue for long, so once again the Tongs won out and raked in the profits.

Kidnapping was also a popular way by which Tong gangs earned an income. Historically Chinese criminals have often fallen back on this practice as a means of achieving monetary gain, kidnapping not only the relatives of the very rich, but also those from middle and working-class backgrounds in the certain knowledge that ransom demands will be met. Where women were concerned, however, the outcome was rarely satisfactory as women have not always enjoyed a particularly high status within Chinese society. Families where a girl had been kidnapped were often unwilling to pay a large sum for her return, particularly when it was supposed that her status as a virgin had been compromised and that her prospects for successfully finding a suitable husband were, therefore, substantially reduced. This meant that young women who were kidnapped were just as likely to be sold into slavery or prostitution as they were to be returned safely to their families. These days kidnapping is still prevalent amongst Tongs as it is often seen as the easiest, most effective way in which to earn money or achieve some other goal. A modern twist on the practice is the kidnapping of large numbers of illegal immigrants who are often employed en masse in Chinese sweatshops or other low-paid industries. The target of the kidnapping is the immigrants' employer whose business will not be able to operate without cheap labor, although, if all else fails, the immigrants' families will be targeted for payment. âIn one such case in Baltimore,' reports Peter Huston, âsixty-three men, women and children â a mixture of kidnappers and kidnap victims â were taken into custody by the police from one small three-bedroom house. The victims had been transported to the premises at night in rented U-Hauls and had made little attempt to escape.'

8

Revenge killings are also common among Tong societies, with certain elements of Chinese communities looking upon revenge almost as a tradition that is tightly aligned to the Chinese honor system. But perhaps the most popular illegal activity with which the Tongs are involved, and one which brings in substantial amounts of money, is that of illegal gambling. Often this takes the form of small âfriendly' games between acquaintances, but more frequently the Tongs like to form multi-state, underground gambling rings, which rake in huge revenues while also serving as a means of laundering vast amounts of âdirty' money. Mah-jong, cards and fan-tan are all popular games pursued during these activities and all relatively harmless when played for small stakes, but gamblers are regularly enticed to bet beyond their means and entire businesses can be put up as collateral, with ownership changing hands overnight. In California, recent State law has tried to address this problem by legalizing most forms of gambling, thereby preventing the Tongs from operating illegally and causing misery amongst the Chinese population.