The New Penguin History of the World (105 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

It was already discernible in the sixteenth century when there began the long expansion of world commerce which was to last, virtually uninterrupted except briefly by war, until 1930, and then to be resumed again after another world war. It started by carrying further the shift of economic gravity from southern to north-western Europe, from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, which has already been remarked. One contribution to this was made by political troubles and wars such as ruined Italy in the early sixteenth century; others are comprised in tiny, short-lived but crucial pressures like the Portuguese harassment of Jews which led to so many of them going, with their commercial skills, to the Low Countries at about the same time. The great commercial success story of the sixteenth century was Antwerp’s, though it collapsed after a few decades in political and economic disaster. In the seventeenth century Amsterdam and London surpassed it. In each case an important trade based on a well-populated hinterland provided profits for diversification into manufacturing industry, services and banking. The old banking supremacy of the medieval Italian cities passed first to Flanders and the German bankers of the sixteenth century and then, finally, to Holland and London. The Bank of Amsterdam and even the Bank of England, founded only in 1694, were soon international economic forces. About them clustered other banks and merchant houses undertaking operations of credit and finance. Interest rates came down and the bill of exchange, a medieval invention, underwent an enormous extension of use and became the primary financial instrument of international trade.

This was the beginning of the increasing use of paper, instead of bullion. In the eighteenth century came the first European paper currencies and the invention of the cheque. Joint stock companies generated another form of negotiable security, their own shares. Quotation of these in London coffee-houses in the seventeenth century was overtaken by the foundation of the London Stock Exchange. By 1800 similar institutions existed in many other countries. New schemes for the mobilization of capital and its

deployment proliferated in London, Paris and Amsterdam. Lotteries and tontines at one time enjoyed a vogue; so did some spectacularly disastrous investment booms, of which the most notorious was the great English South Sea ‘Bubble’. But all the time the world was growing more commercial, more used to the idea of employing money to make money, and was supplying itself with the apparatus of modern capitalism.

One effect quickly appeared in the much greater attention paid to commercial questions in diplomatic negotiation from the later seventeenth century and in the fact that countries were prepared to fight over them. The English and Dutch went to war over trade in 1652. This opened a long era during which they, the French and Spanish, fought again and again over quarrels in which questions of trade were important and often paramount.

Governments not only looked after their merchants by going to war to uphold their interests, but also intervened in other ways in the working of the commercial economy. Sometimes they themselves were entrepreneurs and employers; the arsenal at Venice, it has been said, was at one time in the sixteenth century the largest single manufacturing enterprise in the world. They could also offer monopoly privileges to a company under a charter; this made the raising of capital easier by offering better security for a return. In the end people came to think that chartered companies might not be the best way of securing economic advantage and they fell into disfavour (enjoying a last brief revival at the end of the nineteenth century). None the less, such activities closely involved government and so the concerns of businessmen came to shape policy and law.

Occasionally the interplay of commercial development and society seems to throw light on changes with very deep implications indeed. One example came when a seventeenth-century English financier for the first time offered life insurance to the public. There had already begun the practice of selling annuities on individuals’ lives. What was new was the application of actuarial science and the newly available statistics of ‘political arithmetic’ to this business. A reasonable calculation instead of a bet was now possible on a matter hitherto of awe-inspiring uncertainty and irrationality: death. With increasing refinement men would go on to offer (at a price) protection against a widening range of disasters. This would, incidentally, also provide another and very important device for the mobilization of wealth in large amounts for further investment. But the timing of the discovery of life insurance, at the start of what has sometimes been called the ‘Age of Reason’, suggests also that the dimensions of economic change are sometimes very far-reaching indeed. It was one tiny source and expression of a coming secularizing of the universe.

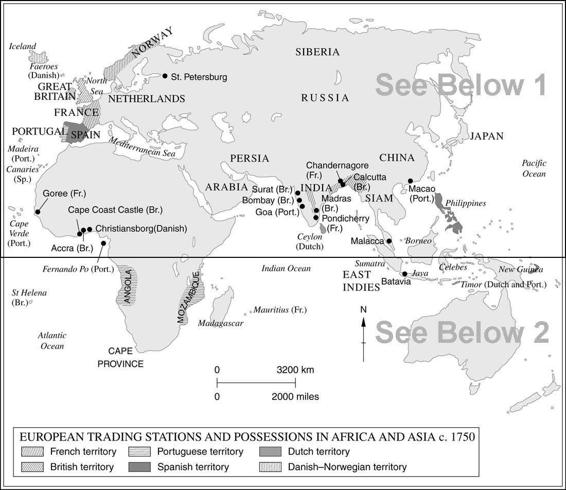

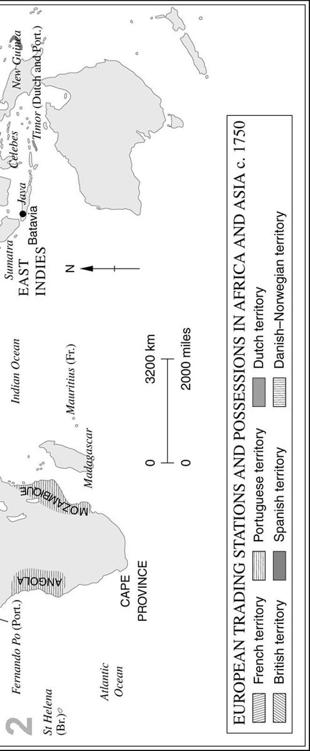

The most impressive structural development in European commerce was the sudden new importance to it of overseas trade from the second half of the seventeenth century onwards. This was part of the shift of economic activity from Mediterranean to northern Europe already observable before 1500, which first made visible the lineaments of a future world economy. Until about 1580, though, these were still largely drawn by the Iberian peoples. They not only dominated the South Atlantic and Caribbean trades, but after 1564 there were regular sailings of ‘Manila galleons’ from Acapulco to the Philippines; so China was brought into commercial touch with Europeans from further east, even as the Portuguese established themselves from the west. Global commerce was beginning to eclipse the old Mediterranean trade. By the late seventeenth century, while the closed trade of Spain and Portugal with their transatlantic colonies was still important, overseas commerce was dominated by the Dutch and their increasingly successful rivals, the English. Dutch success had grown out of the supply of salted herrings to European markets and the possession of a particularly suitable bulk-carrying vessel, the ‘flute’ or fly-boat. With this the Dutch first dominated the Baltic trade; from it they advanced to become the carriers of Europe. Though often displaced by the English in the later seventeenth century, they maintained a far-flung network of colonies and trading stations, especially in the Far East, where they overpowered the Portuguese. The basis of English supremacy, though, was the Atlantic. Fish were important here, too; the English caught the nutritious cod on the Newfoundland banks, dried it and salted it ashore, and then sold it in Mediterranean countries, where fish was in great demand because of the practice of fasting on Fridays.

Bacalao

, as it was called, can still be found on the tables of Portugal and southern Spain, once the tourist coast is left behind. Gradually, both Dutch and English broadened and diversified their carrying trade and became dealers themselves, too. Nor was France out of the race; her overseas trade doubled in the first half of the seventeenth century.

Rising populations and some assurance of adequate transport (water was always cheaper than land carriage) slowly built up an international trade in cereals. Shipbuilding itself promoted the movement of such commodities as pitch, flax or timber, staples first of Baltic trade and later important in the economy of North America. More than European consumption was involved; all this took place in a setting of growing colonial empires. By the eighteenth century we are already in the presence of an oceanic economy and an international trading community which does business – and fights and intrigues for it – around the globe.

In this economy an important and growing part was played by slaves. Most of them were black Africans, the first of whom to be brought to Europe were sold at Lisbon in 1444. In Europe itself, slavery had by then all but withered away (although Europeans were still being enslaved and sold into slavery by Arabs and Turks). Now it was to undergo a vast extension in other continents. Within two or three years over a thousand more blacks had been sold by the Portuguese, who soon set up a permanent slaving station in West Africa. Such figures show the rapid discovery of the profitability of the new traffic but gave little hint of the scale of what was to come. What was already clear was the brutality of the business (the Portuguese quickly noted that the seizure of children usually ensured the docile captivity of the parents) and the complicity of Africans in it; as the search for slaves went further inland, it became simple to rely on local potentates who would round up captives and barter them wholesale.

For a long time, Europe and the Portuguese and Spanish settlements in the Atlantic islands took almost all the slaves West Africa supplied. Then came a change. From the mid-sixteenth century African slaves were shipped across the Atlantic to Brazil, the Caribbean islands and the North American mainland. The trade thus entered upon a long period of dramatic growth, whose demographic, economic and political consequences are still with us. African slaves are by no means the only ones important in modern history, nor were Europeans the only slavers. None the less, black slavery based

on the selling by Africans of other Africans to Portuguese, Englishmen, Dutchmen and Frenchmen, and their subsequent sale to other Europeans in the Americas, is a phenomenon whose repercussions have been much more profound than the enslavement of Europeans by Ottomans or Africans by Arabs. The approximate numbers of those enslaved, too, have seemed easier to establish, if only approximately. Much of the labour which made American colonies possible and viable was supplied by black slaves, though for climatic reasons the slave population was not uniformly spread among them. Always the great majority of slaves worked in agriculture or domestic service: black craftsmen or, later, factory workers were unusual.

The slave trade was commercially very important, too. Huge profits were occasionally made – a fact which partly explains the crammed and pestilential holds of the slave-ships in which were confined the human cargoes. They rarely had a death rate per voyage of less than 10 per cent and sometimes suffered much more appalling mortality. The supposed value of the trade made it a great and contested prize, though the normal return on capital has been much exaggerated. For two centuries it provoked diplomatic wrangling and even war as nation after nation sought to break into it or monopolize it. This testified to the trade’s importance in the eyes of statesmen, whether it was economically justified or not.

It was once widely held that the slave trade’s profits provided the capital for European industrialization, but this no longer seems plausible. Industrialization was a slow process. Before 1800, though examples of industrial concentration could be found in several European countries, the growth of both manufacturing and extractive industry was still in the main a matter of the multiplication of small-scale artisan production and its technical elaboration, rather than of radically new methods and institutions. Europe had by 1500 an enormous pool of wealth to draw on in her large numbers of skilled craftsmen, already used to investigating new processes and exploring new techniques. Two centuries of gunnery had brought mining and metallurgy to a high pitch. Scientific instruments and mechanical clocks testified to a wide diffusion of skill in the making of precision goods. Such advantages as these shaped the early pattern of the industrial age and soon began to reverse a traditional relationship with Asia. For centuries oriental craftsmen had astounded Europeans by their skill and the quality of their work. Asian textiles and ceramics had a superiority which lives in our everyday language: china, muslin, calico, shantung are still familiar words. Then, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, supremacy in some forms of craftsmanship had passed to Europe, notably in mechanical and engineering skills. Asian potentates began to seek Europeans who could teach

them how to make effective firearms; they even collected mechanical toys which were the commonplaces of European fairs. Such a reversal of roles was based on Europe’s accumulation of skills in traditional occupations and their extension into new fields. This happened usually in towns; craftsmen often travelled from one to another, following demand. So much it is easy to see. It is harder to see what it was in the European mind that pressed the European craftsman forward and also stimulated the interest of his social betters so that a craze for mechanical engineering is as important an aspect of the age of the Renaissance as is the work of its architects and goldsmiths. After all, this did not happen elsewhere.