The New Penguin History of the World (109 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

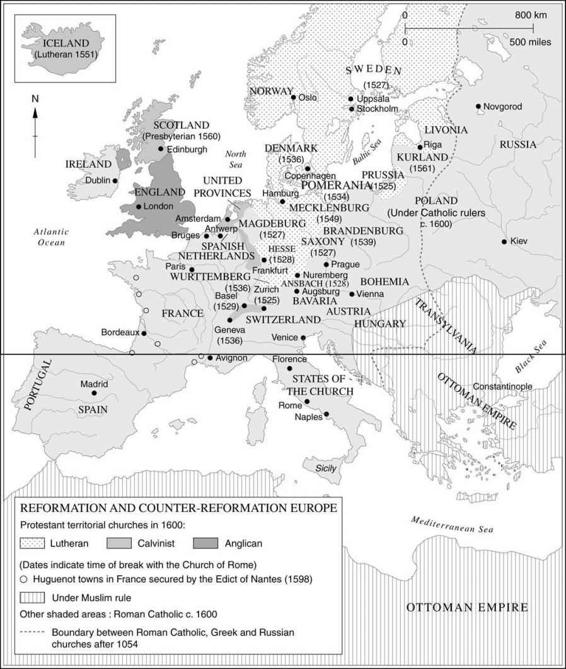

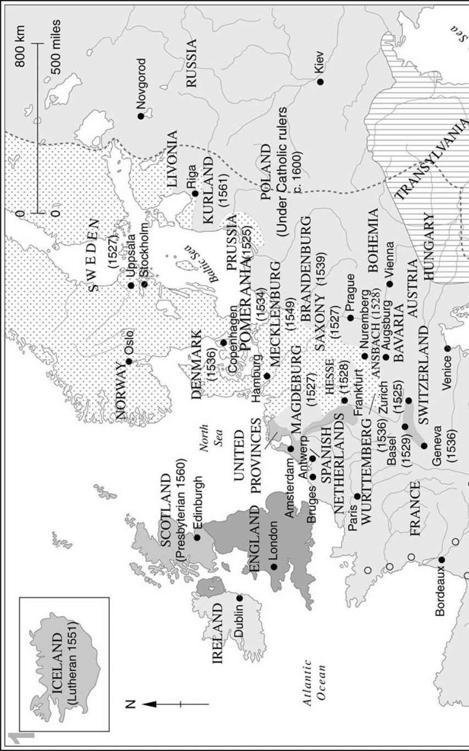

But there was no simple Reformation phenomenon; other varieties of Protestantism had by then emerged from the evangelical ferment. Some drew on social unrest. Luther soon had to distinguish his own teaching from the views of peasants who invoked his name to justify rebellion against their masters. One radical group were the Anabaptists, persecuted by Catholic and Protestant rulers alike. At Munster in 1534 their leaders’ introduction of communism of property and polygamy confirmed their opponents’ fears and brought a ferocious suppression upon them. But of other forms of Protestantism, only Calvinism can be noticed in so general an account as this. It was to be Switzerland’s most important contribution to the Reformation, though created by a Frenchman, John Calvin. He was

a theologian who formulated his essential doctrines while still a young man: the absolute depravity of man after the Fall of Adam and the impossibility of salvation except for those few, the Elect, predestined by God to salvation. If Luther, the Augustinian monk, spoke with the voice of Paul, Calvin evoked the tones of Augustine. It is not easy to understand the success of this gloomy creed. But to its efficacy, the history not only of Geneva, but of France, England, Scotland, the Dutch Netherlands, and British North America all witness. The crucial step was conviction of membership of the Elect. As the signs of this were outward adherence to the commandments of God and participation in the sacraments, it was less difficult to achieve such conviction than might be imagined.

Under Calvin, Geneva was not a place for the easy-going. He had drawn up the constitution of a theocratic state which provided the framework for a remarkable exercise in self-government. Blasphemy and witchcraft were punished by death, but this would not have struck contemporaries as surprising. Adultery, too, was a crime in most European countries and one punished by ecclesiastical courts. But Calvin’s Geneva took this offence much more seriously and imposed the death penalty for it; adulterous women were drowned, men beheaded (an apparent reversal of the normal penal practice of a male-dominated European society where women, considered weaker vessels morally and intellectually, were usually indulged with milder punishments than men). Severe punishments, too, were reserved for those guilty of heresy.

From Geneva, where its pastors were trained, the new sect took root in France, where it won converts among the nobility and had more than 2000 congregations by 1561. In the Netherlands, England and Scotland and, in the end, Germany, it challenged Lutheranism. It spread also to Poland, Bohemia and Hungary. Calvinism’s early vigour surpassed that of Lutheranism which, except in Scandinavia, was never strongly entrenched beyond the German lands which first adopted it.

The variety of the Protestant Reformation still defies summary and simplification. Complex and deep-rooted in its origins, it also owed much to circumstance and was varied, rich and far-reaching in its effects and expressions. If the name ‘Protestantism’ can be taken seriously as an indicator of fundamental indentity beneath the disorder of its many expressions, that identity is to be found in its influence and effect. It was disruptive. In Europe and the Americas it created new ecclesiastical cultures founded on the study of the Bible and preaching, to which it gave an importance sometimes surpassing that of the sacraments. It was to shape the lives of millions by accustoming them to a new and an intense scrutiny of private conduct and conscience (thus, ironically, achieving something long sought by Roman Catholics) and it re-created the non-celibate clergy. Negatively, it slighted or at least called in question all existing ecclesiastical institutions and created new political forces in the form of churches which princes could now manipulate for their own ends – often against popes whom they saw simply as princes like themselves. Rightly Protestantism was to come to be seen by friend and foe alike, as one of the forces determining the shape of modern Europe and therefore of the world.

Yet neither Lutheranism nor Calvinism provoked the first rejection of papal authority by a nation-state. In England a unique religious change arose almost by accident. A new dynasty originating in Wales, the Tudors, had established itself at the end of the fifteenth century and the second

king of this line, Henry VIII, became entangled with the papacy over his wish to dissolve the first of his six marriages in order to remarry and get an heir, an understandable preoccupation. This led to a quarrel and one of the most remarkable assertions of lay authority in the whole sixteenth century; it was also one fraught with significance for England’s future. With the support of his parliament, which obediently passed the required legislation, Henry VIII proclaimed himself Head of the Church in England. Doctrinally, he conceived no break with the past; he was, after all, entitled Defender of the Faith by the pope because of a refutation of Luther from the royal pen (his descendant still bears that title). But the assertion of the royal supremacy opened the way to an English Church separate from Rome. A vested interest in it was soon provided by a dissolution of monasteries and some other ecclesiastical foundations and the sale of property to buyers among the aristocracy and gentry. Churchmen sympathetic to new doctrines sought to move the Church in England significantly towards continental Protestant ideas in the next reign. Popular reactions were mixed. Some saw this as the satisfaction of old national traditions of dissent from Rome; some resented innovations. From a confused debate and murky politics emerged a literary masterpiece, the Book of Common Prayer, and some martyrs both Catholic and Protestant. There was a reversion to papal authority (and the burning of Protestant heretics) under the fourth Tudor, the unfairly named and unhappy Bloody Mary, perhaps England’s most tragic queen. By this time, moreover, the question of religion was thoroughly entangled with national interest and foreign policy, for the states of Europe drew apart more and more on religious grounds.

This was not all that was notable about the English Reformation which, like the German, was a landmark in the evolution of a national consciousness. It had been carried out by Act of Parliament and a constitutional question was implicit in the religious settlement: were there any limits to legislative authority? With the accession of Mary’s half-sister, Elizabeth I, the pendulum swung back, though for a long time it was unclear how far. Yet Elizabeth insisted, and her parliament legislated, that she retain the essentials of her father’s position; the English Church, or Church of England, as it may henceforth be called, claimed to be Catholic in doctrine but rested on the royal supremacy. More important still, because that supremacy was recognized by Act of Parliament, England would before long be at war with a Catholic king of Spain, who was well known for his determination to root out heresy in the lands he subjugated. So another national cause was identified with that of Protestantism.

Reformation helped the English parliament to survive when other medieval representative bodies were going under before monarchical power

though this was far from the whole story. A kingdom united since Anglo-Saxon times and without provincial assemblies which might rival it made it much easier for parliament to focus national politics than any similar body elsewhere. Royal carelessness helped, too; Henry VIII had squandered a great opportunity to achieve a sound basis for absolute monarchy when he rapidly liquidated the mass of property – about a fifth of the land of the whole kingdom – which he held briefly as a result of the dissolutions. Nevertheless, all such imponderables duly weighed, the fact that Henry chose to seek endorsement of his will from the national representative body in creating a national church still seems one of the most crucial decisions in Parliament’s history.

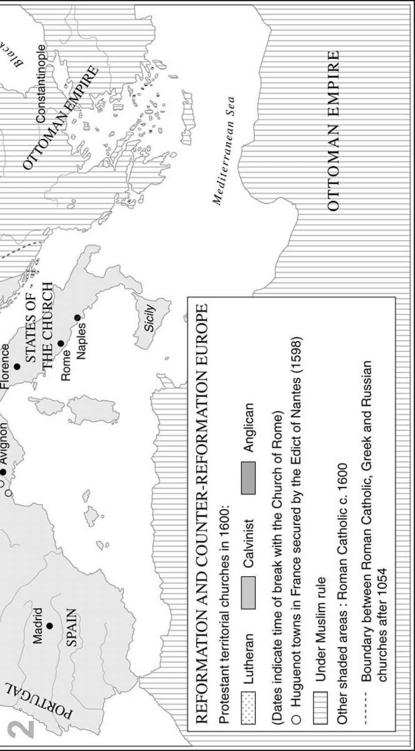

Catholic martyrs died under Elizabeth because they were judged traitors, not because they were heretics – but England was far less divided by religion than Germany and France. Sixteenth-century France was tormented and torn between Catholic and Calvinist interests. Each was in essence a group of noble clans, who fought for power in the Wars of Religion, of which nine have been distinguished between 1562 and 1598. At times their struggles brought the French monarchy very low; the nobility of France came near to winning the battle against the centralizing state. Yet, in the end, their divisions benefited a crown which could use one faction against another. The wretched population of France had to bear the brunt of disorder and devastation until there came to the throne in 1589 (after the murder of his predecessor) a member of a junior branch of the royal family, Henry, king of the little state of Navarre, who became Henry IV of France and inaugurated the Bourbon line whose descendants still claim the French throne. He had been a Protestant, but accepted Catholicism as the condition of his succession, recognizing that Catholicism was the religion most Frenchmen would cling to – a continuing strain in the identity of nationhood. The Protestants were assured special guarantees which left them a state within a state, the possessors of fortified towns where the king’s writ did not run; this very old-fashioned sort of solution assured protection for their religion by creating new immunities. Henry and his successors could then turn to the business of re-establishing the authority of a throne badly shaken by assassination and intrigue. But the French nobility were still far from tamed.

Before this, religious antagonism had been further inflamed by the internal re-assessment of the Roman Church which we remember as the Counter-Reformation. Its most formal expression was the Council of Trent, a general council summoned in 1543 which met in three sessions over the next thirteen years. It was dominated by bishops from Italy and Spain, and that helped to shape it, for Reform challenged the Church

little in Italy and not at all in Spain. The Council’s decisions became the touchstone of orthodoxy in discipline and doctrine until the nineteenth century, providing standards to which Catholic rulers would rally. Bishops were given more authority and parishes took on new importance. The Council answered by implication, too, the old question about the leadership of Catholic Europe; from this time, it lay indisputably with the Pope. Like Reformation, though, Counter-Reformation went beyond forms and principles in a new devotional intensity, rejuvenating the fervour of laity and clergy alike. Besides making weekly attendance at mass obligatory, regulating baptism and marriage more strictly, and ending the selling of indulgences by ‘pardoners’ (the very practice which had detonated the Lutheran explosion), it sought, too, to redeem rural districts sunk in traditional superstition and an ignorance so deep that the missionaries who sought to penetrate them in Italy spoke of them as ‘our Indies’, by implication in as great a need of the Gospel as were the heathen of the New World.

Yet a spirituality and spontaneous fervour already apparent among the faithful in the fifteenth century fed the Counter-Reformation too. One of the most potent expressions of its new mood, as well as an institution which was to prove enduring, was the invention of a Spaniard, the soldier Ignatius Loyola. By a curious irony he had been a student at the same Paris college as Calvin in the early 1530s, but it is not recorded that they ever met. In 1534 he and a few companions took vows; their aim was missionary work and as they trained for it Loyola devised a rule for a new religious order. In 1540 it was recognized by the pope and named the Society of Jesus. The Jesuits, as they soon came to be called, were to have an importance in the history of the Church akin to that of the early Benedictines or the Franciscans of the thirteenth century. Their warrior-founder liked to think of them as the militia of the Church, utterly disciplined and completely subordinate to papal authority through their general, who lived in Rome. They transformed Catholic education. They were in the forefront of missionary efforts in every part of the world. In Europe their intellectual eminence and political skill raised them to high places in the courts of kings.