The Pillow Book of the Flower Samurai (61 page)

Read The Pillow Book of the Flower Samurai Online

Authors: Barbara Lazar

Author’s Notes

PILLOW BOOK

Noble women, and also peasants, who travelled on pilgrimages wrote a ‘journal’. The women stored these journals near their pillows, hence the name. After a journal entry, a poem or two often followed.

The Pillow Book of the Flower Samurai

emulates this custom.

For more reading, the

Tale of The Lady Ochikubo, The Pillow Book of Sei Sh

ō

nagon

, and

As I Crossed a Bridge of Dreams

are some of the translated pillow books from the tenth and eleventh centuries, although, none of these women is a samurai, like Kozaishō.

MEASURING TIME

The Japanese adopted a sexagenary system, or Zodiac Calendar, linking the cycle of twelve months and twelve hours of the day (Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Sheep, Monkey, Rooster, Dog and Boar) with the five elements (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal and Water). (Morris, Ivan, translator & editor.

The Pillow Book of Sei Sh

ō

nagon

. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991, page 380.)

Rather than Sunday through Monday, days continue cycling through the twelve divisions: Rat, Ox, Tiger, etc. Days are delineated as the Third Month, Second Day of the Rabbit, or Fourth Month, First Day of the Monkey, etc.

For people, the animal of the birth year, the elements (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal and Water) and the alternating principles of yang (masculine/positive) and yin (feminine/negative) combined to create multifaceted personality configurations. Therefore each year included three different ‘wheels’ of features: animal, element and yang/yin. Please note that men are not inevitably yang, nor are women unavoidably yin. Yang and yin represents personality types, rather than gender.

I simplified to the element and yang/yin to avoid digressing into personality types and detracting from the story. Example: Kozaishō is a Fire and yang personality. She is a leader, promoter who is determined, zealous and always looking for something new. Misuki is Water and yin, a bubbly personality. She is also receptive, easy-going, philosophical, superficial and passionate. Hitomi is Metal and yang, a good motivator who can succeed in almost any profession. Akio and Tashiko are Earth, the former yang and the latter, yin. The Metal yang is ready to fight for truth and righteousness. The Metal yin is liked by others, strong yet compliant, gentle yet confident and tolerant.

RELIGION

The Japanese adopted Buddhism in the sixth century, while maintaining their Shinto beliefs. For centuries Buddhism was the religion of the aristocrats. Kozaishō, as the daughter of a cultivator, originally held Shinto beliefs. Part of this belief system included clapping to dispel evil spirits and a strong sense of ritual cleanliness, which Buddhism absorbed. Part of ritual cleanliness included, for example, ritual defilements such as menstruation and death. The washing of hands and rinsing the mouths before entering sacred areas is a Shinto concept.

Each temple and shrine associated itself with a particular sect of Buddhism or Shintoism and could be sponsored by political figures (head of a clan, emperor, Prince). Each maintained its own military force, sōhei, and was mostly tax exempt. The political, religious, social and military lines crisscrossed repeatedly, particularly in the latter Heian period, the time of

The Pillow Book of the Flower Samurai

.

MARRIAGE, VIRGINITY, MONOGAMY AND POLYGAMY

None of the Judaic-Christian-Islamic influences had entered Heian Japan. Virginity, at least among the aristocrats, was not a state to be desired in men or women. Moreover, adult virgins were considered suspicious and possibly corrupt or dangerous. Non-royal aristocratic marriages involved a man staying three nights in a row with his ‘intended’. If he did not return after the first or second night, they were not married and each moved on. Children of such unions were simply acknowledged and accepted.

Polygamy functioned contrarily to what is commonly assumed in current times. When a man married, he moved in with his wife. Women generally inherited their parents’ homes and property. (Court cases exist of widows suing for their property and winning.) Polygamous men travelled from household to household, i.e. wife to wife. However, Rokuhara reversed this by a wife (or wives) living in her (or their) husband’s home.

Aristocratic women, and Kozaishō (after she married), customarily did not to show their faces to any men other than their husbands and families. The curtained platform used for this was the

kich

ō

(servants did not count.) Ironically among the aristocrats, according to diaries and

Tale of the Genji

, a man might sleep with someone he had never seen. While married women of the samurai were expected to be faithful, divorce was common, easy and frequently initiated by women and men alike.

POLICE

The Ministry of Justice existed in Heian Japan. Yet because of its impotence in protecting the populace early on in the Heian period, the offices of Ōryoshi and Tsuibushi were established. These positions were called ‘Sheriffs’ and ‘Chief Constables’. (Samsom in

The History of Japan to 1334

.) I simplified this by using the term Constable.

ADDENDUM

I have endeavoured to write this account of a most dramatic and turbulent time in Japanese history with as much historical accuracy as I could. Those appreciated and named in the acknowledgements assisted me significantly.

But I must admit a major exception. The aristocrats in Heian-Kyō (present day Kyōtō) did not bathe much, if at all. They actually slept in their clothes, although it can be assumed they changed them at least once a season. I added the bathing to comfort modern readers who use and venerate running water.

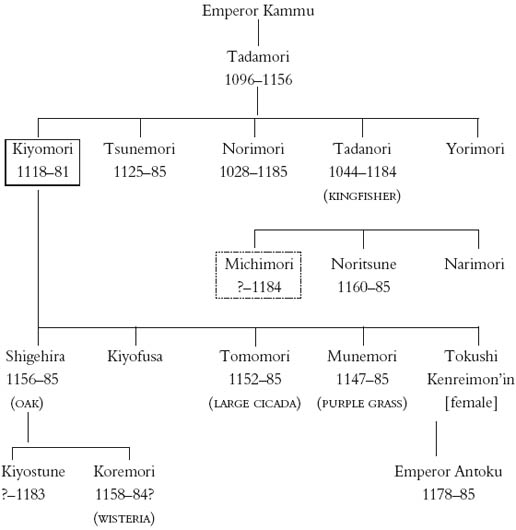

Taira Clan Genealogy

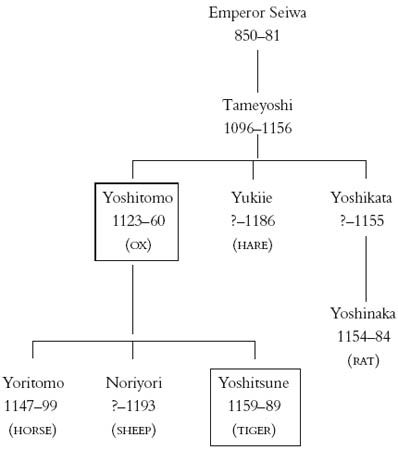

Minamoto Clan Genealogy

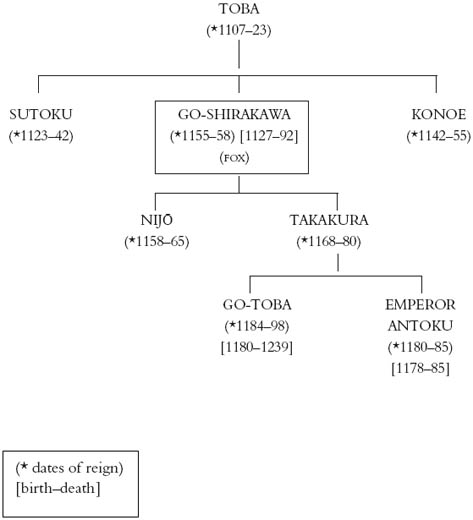

Genealogy of Emperors of the Late Heian Japan