The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business (26 page)

Read The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business Online

Authors: Charles Duhigg

Tags: #Psychology, #Organizational Behavior, #General, #Self-Help, #Social Psychology, #Personal Growth, #Business & Economics

Rhode Island Hospital was a place filled with a corrosive culture. Unlike at Alcoa, where carefully designed keystone habits surrounding worker safety had created larger and larger successes, inside Rhode Island Hospital, habits emerged on the fly among nurses seeking to offset physician arrogance. The hospital’s routines weren’t

carefully thought out. Rather, they appeared by accident and spread through whispered warnings, until toxic patterns emerged. This can happen within any organization where habits aren’t deliberately planned. Just as choosing the right keystone habits can create amazing change, the wrong ones can create disasters.

And when the habits within Rhode Island Hospital imploded, they caused terrible mistakes.

When the emergency room staff saw the brain scans of the eighty-six-year-old man with the subdural hematoma, they immediately paged the neurosurgeon on duty. He was in the middle of a routine spinal surgery, but when he got the page, he stepped away from the operating table and looked at images of the elderly man’s head on a computer screen. The surgeon told his assistant—a nurse practitioner—to go to the emergency room and get the man’s wife to sign a consent form approving surgery. He finished his spinal procedure.

A half hour later, the elderly man was wheeled into the same operating theater.

6.7

Nurses were rushing around. The unconscious elderly man was placed on the table. A nurse picked up his consent form and medical chart.

“Doctor,” the nurse said, looking at the patient’s chart. “The consent form doesn’t say where the hematoma is.” The nurse leafed through the paperwork.

There was no clear indication of which side of his head they were supposed to operate on.

6.8

Every hospital relies upon paperwork to guide surgeries. Before any cut is made, a patient or family member is supposed to sign a document approving each procedure and verifying the details. In a chaotic environment, where as many as a dozen doctors and nurses may handle a patient between the ER and the recovery suite, consent forms are the instructions that keep track of what is supposed

to occur. No one is supposed to go into surgery without a signed and detailed consent.

“I saw the scans before,” the surgeon said. “It was the right side of the head. If we don’t do this quickly, he’s gonna die.”

“Maybe we should pull up the films again,” the nurse said, moving toward a computer terminal. For security reasons, the hospital’s computers locked after fifteen minutes of idling. It would take at least a minute for the nurse to log in and load the patient’s brain scans onto the screen.

“We don’t have time,” the surgeon said. “They told me he’s crashing. We’ve got to relieve the pressure.”

“What if we find the family?” the nurse asked.

“If that’s what you want, then call the fucking ER and find the family! In the meantime, I’m going to save his life.” The surgeon grabbed the paperwork, scribbled “right” on the consent form, and initialed it.

“There,” he said.

“We have to operate immediately.”

6.9

The nurse had worked at Rhode Island Hospital for a year. He understood the hospital’s culture. This surgeon’s name, the nurse knew, was often scribbled in black on the large whiteboard in the hallway, signaling that nurses should beware. The unwritten rules in this scenario were clear: The surgeon always wins.

The nurse put down the chart and stood aside as the doctor positioned the elderly man’s head in a cradle that provided access to the right side of his skull and shaved and applied antiseptic to his head. The plan was to open the skull and suction out the blood pooling on top of his brain. The surgeon sliced away a flap of scalp, exposed the skull, and put a drill against the white bone. He began pushing until the bit broke through with a soft pop. He made two more holes and used a saw to cut out a triangular piece of the man’s skull. Underneath was the dura, the translucent sheath surrounding the brain.

“Oh my God,” someone said.

There was no hematoma. They were operating on the wrong side of the head.

“We need him turned!”

the surgeon yelled.

6.10

The triangle of bone was replaced and reattached with small metal plates and screws, and the patient’s scalp sewed up. His head was shifted to the other side and then, once again, shaved, cleansed, cut, and drilled until a triangle of skull could be removed. This time, the hematoma was immediately visible, a dark bulge that spilled like thick syrup when the dura was pierced. The surgeon vacuumed the blood and the pressure inside the old man’s skull fell immediately. The surgery, which should have taken about an hour, had run almost twice as long.

Afterward, the patient was taken to the intensive care unit, but he never regained full consciousness. Two weeks later, he died.

A subsequent investigation said it was impossible to determine the precise cause of death, but the patient’s family argued that the trauma of the medical error had overwhelmed his already fragile body, that the stress of removing two pieces of skull, the additional time in surgery, and the delay in evacuating the hematoma had pushed him over the edge. If not for the mistake, they claimed, he might still be alive. The hospital paid a settlement and the surgeon was barred from

ever working at Rhode Island Hospital again.

6.11

Such an accident, some nurses later claimed, was inevitable. Rhode Island Hospital’s institutional habits were so dysfunctional, it was only a matter of time until a grievous mistake occurred.

1

It’s not just hospitals that breed dangerous patterns, of course. Destructive organizational habits can be found within hundreds of industries and at thousands of firms. And almost always, they are the

products of thoughtlessness, of leaders who avoid thinking about the culture and so let it develop without guidance. There are no organizations without institutional habits. There are only places where they are deliberately designed, and places where they are created without forethought, so they often grow from rivalries or fear.

But sometimes, even destructive habits can be transformed by leaders who know how to seize the right opportunities. Sometimes, in the heat of a crisis, the right habits emerge.

When

An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change

was first published in 1982, very few people outside of academia noticed.

The book’s bland cover and daunting first sentence—“In this volume we develop an evolutionary theory of the capabilities and behavior of business firms operating in a market environment, and construct and analyze a number of models consistent with that theory”—almost seemed designed to ward off readers.

6.12

The authors, Yale professors Richard Nelson and Sidney Winter, were best known for a series of intensely analytic papers exploring Schumpeterian theory that even most PhD

candidates didn’t pretend to understand.

6.13

Within the world of business strategy and organizational theory, however, the book went off like a bombshell.

6.14

It was soon hailed as one of the most important texts of the century. Economics professors started talking about it to their colleagues at business schools, who started talking to CEOs at conferences, and soon executives were quoting Nelson and Winter inside corporations as different as General Electric, Pfizer, and Starwood Hotels.

Nelson and Winter had spent more than a decade examining how companies work, trudging through swamps of data

before arriving at their central conclusion: “Much of firm behavior,” they wrote, is best “understood as a reflection of general habits and strategic

orientations coming from the firm’s past,” rather than “the result of a detailed survey of the remote twigs of the decision tree.”

6.15

Or, put in language that people use outside of theoretical economics, it may

seem

like most organizations make rational choices based on deliberate decision making, but that’s not really how companies operate at all. Instead, firms are guided by long-held organizational habits, patterns that often emerge from

thousands of employees’ independent decisions.

6.16

And these habits have more profound impacts than anyone previously understood.

For instance, it might seem like the chief executive of a clothing company made the decision last year to feature a red cardigan on the catalog’s cover by carefully reviewing sales and marketing data. But, in fact, what really happened was that his vice president constantly trolls websites devoted to Japanese fashion trends (where red was hip last spring), and the firm’s marketers routinely ask their friends which colors are “in,” and the company’s executives, back from their annual trip to the Paris runway shows, reported hearing that designers at rival firms were using new magenta pigments. All these small inputs, the result of uncoordinated patterns among executives gossiping about competitors and talking to their friends, got mixed into the company’s more formal research and development routines until a consensus emerged: Red will be popular this year. No one made a solitary, deliberate decision. Rather, dozens of habits, processes, and behaviors converged until it seemed like red was the inevitable choice.

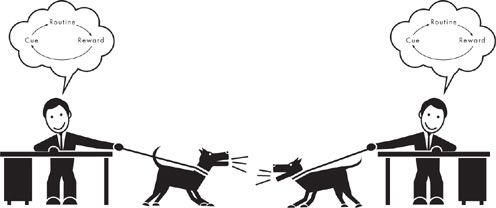

These organizational habits—or “routines,” as Nelson and Winter called them—are enormously important, because without them, most companies would never get any work done.

6.17

Routines provide the

hundreds of unwritten rules that

companies need to operate.

6.18

,

6.19

They allow workers to experiment with new ideas without having to ask for permission at every step.

They provide a kind of “organizational memory,” so that managers don’t have to reinvent the sales

process every six months or panic each time a VP quits.

6.20

Routines reduce uncertainty—a study of recovery efforts after earthquakes in Mexico and Los Angeles, for instance, found that the habits of relief workers (which they carried from disaster to disaster, and which included things such as establishing communication networks by hiring children to carry messages between neighborhoods) were absolutely critical, “because without them, policy formulation and implementation would be lost in a jungle of detail.”

6.21

But among the most important benefits of routines is that they create truces between potentially warring groups or individuals within an organization.

6.22

Most economists are accustomed to treating companies as idyllic places where everyone is devoted to a common goal: making as much money as possible. Nelson and Winter pointed out that, in the real world, that’s not how things work at all. Companies aren’t big happy families where everyone plays together nicely. Rather, most workplaces are made up of fiefdoms where executives compete for power and credit, often in hidden skirmishes that make their own performances appear superior and their rivals’ seem worse. Divisions compete for resources and sabotage each other to steal glory. Bosses pit their subordinates against one another so that no one can mount a coup.

Companies aren’t families. They’re battlefields in a civil war.

Yet despite this capacity for internecine warfare, most companies roll along relatively peacefully, year after year, because they have routines—habits—that create truces that allow everyone to set aside their rivalries long enough to get a day’s work done.

Organizational habits offer a basic promise: If you follow the established patterns and abide by the truce, then rivalries won’t destroy the company, the profits will roll in, and, eventually, everyone will get rich. A salesperson, for example, knows she can boost her bonus by giving favored customers hefty discounts in exchange for larger orders. But she also knows that if every salesperson gives

away hefty discounts, the firm will go bankrupt and there won’t be any bonuses to hand out. So a routine emerges: The salespeople all get together every January and agree to limit how many discounts they offer in order to protect the company’s profits, and at the end of the year everyone gets a raise.

Or take a young executive gunning for vice president who, with one quiet phone call to a major customer, could kill a sale and sabotage a colleague’s division, taking him out of the running for the promotion. The problem with sabotage is that even if it’s good for you, it’s usually bad for the firm. So at most companies, an unspoken compact emerges: It’s okay to be ambitious, but if you play

too

rough, your peers will unite against you. On the other hand, if you focus on boosting your own department, rather than undermining your rival,

you’ll probably get taken care of over time.

6.23

ROUTINES CREATE TRUCES THAT ALLOW WORK TO GET DONE