The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business (27 page)

Read The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business Online

Authors: Charles Duhigg

Tags: #Psychology, #Organizational Behavior, #General, #Self-Help, #Social Psychology, #Personal Growth, #Business & Economics

Routines and truces offer a type of rough organizational justice, and because of them, Nelson and Winter wrote, conflict within companies usually “follows largely predictable paths and stays within predictable bounds that are consistent with the ongoing routine.… The usual amount of work gets done, reprimands and compliments are delivered with the usual frequency.… Nobody is trying to steer the organizational ship into a sharp turn in the hope

of throwing a rival overboard.”

6.24

Most of the time, routines and truces work perfectly. Rivalries still exist, of course, but because of institutional habits, they’re kept within bounds and the business thrives.

However, sometimes even a truce proves insufficient. Sometimes, as Rhode Island Hospital discovered, an unstable peace can be as destructive as any civil war.

Somewhere in your office, buried in a desk drawer, there’s probably a handbook you received on your first day of work. It contains expense forms and rules about vacations, insurance options, and the company’s organizational chart. It has brightly colored graphs describing different health care plans, a list of relevant phone numbers, and instructions on how to access your email or enroll in the 401(k).

Now, imagine what you would tell a new colleague who asked for advice about how to

succeed

at your firm. Your recommendations probably wouldn’t contain anything you’d find in the company’s handbook. Instead, the tips you would pass along—who is trustworthy; which secretaries have more clout than their bosses; how to manipulate the bureaucracy to get something done—are the habits you rely on every day to survive. If you could somehow diagram all your work habits—and the informal power structures, relationships, alliances, and conflicts they represent—and then overlay your diagram with diagrams prepared by your colleagues, it would create a map of your firm’s secret hierarchy, a guide to who knows how to make things happen and who never seems to get ahead of the ball.

Nelson and Winter’s routines—and the truces they make possible—are critical to every kind of business. One study from Utrecht University in the Netherlands, for instance, looked at routines within the world of high fashion. To survive, every fashion designer has to possess some basic skills: creativity and a flair for

haute couture as a start.

But that’s not enough to succeed.

6.25

What makes the difference between success or failure are a designer’s routines—whether they have a system for getting Italian broadcloth before wholesalers’ stocks sell out, a process for finding the best zipper and button seamstresses, a routine for shipping a dress to a store in ten days, rather than three weeks. Fashion is such a complicated business that, without the right processes, a new company will get bogged down with logistics, and once that happens, creativity ceases to matter.

And which new designers are most likely to have the right habits? The ones who have formed the right truces

and found the right alliances.

6.26

Truces are so important that new fashion labels usually succeed only if they are headed by people who left

other

fashion companies on good terms.

Some might think Nelson and Winter were writing a book on dry economic theory. But what they really produced was a guide to surviving in corporate America.

What’s more, Nelson and Winter’s theories also explain why things went so wrong at Rhode Island Hospital. The hospital had routines that created an uneasy peace between nurses and doctors—the whiteboards, for instance, and the warnings nurses whispered to one another were habits that established a baseline truce. These delicate pacts allowed the organization to function most of the time. But truces are only durable when they create real justice. If a truce is unbalanced—if the peace isn’t real—then the routines often fail when they are needed most.

The critical issue at Rhode Island Hospital was that the nurses were the only ones giving up power to strike a truce. It was the nurses who double-checked patients’ medications and made extra efforts to write clearly on charts; the nurses who absorbed abuse from stressed-out doctors; the nurses who helped separate kind physicians from the despots, so the rest of the staff knew who tolerated operating-room suggestions and who would explode if you

opened your mouth. The doctors often didn’t bother to learn the nurses’ names. “The doctors were in charge, and we were underlings,” one nurse told me. “We tucked our tails and survived.”

The truces at Rhode Island Hospital were one-sided. So at those crucial moments—when, for instance, a surgeon was about to make a hasty incision and a nurse tried to intervene—the routines that could have prevented the accident crumbled, and the wrong side of an eighty-six-year-old man’s head was opened up.

Some might suggest that the solution is more equitable truces. That if the hospital’s leadership did a better job of allocating authority, a healthier balance of power might emerge and nurses and doctors would be forced into a mutual respect.

That’s a good start. Unfortunately, it isn’t enough. Creating successful organizations isn’t just a matter of balancing authority. For an organization to work, leaders must cultivate habits that both create a real and balanced peace and, paradoxically, make it absolutely clear who’s in charge.

Philip Brickell, a forty-three-year-old employee of the London Underground, was inside the cavernous main hall of the King’s Cross subway station on a November evening in 1987 when a commuter stopped him as he was collecting tickets and said there was a burning tissue

at the bottom of a nearby escalator.

6.27

,

6.28

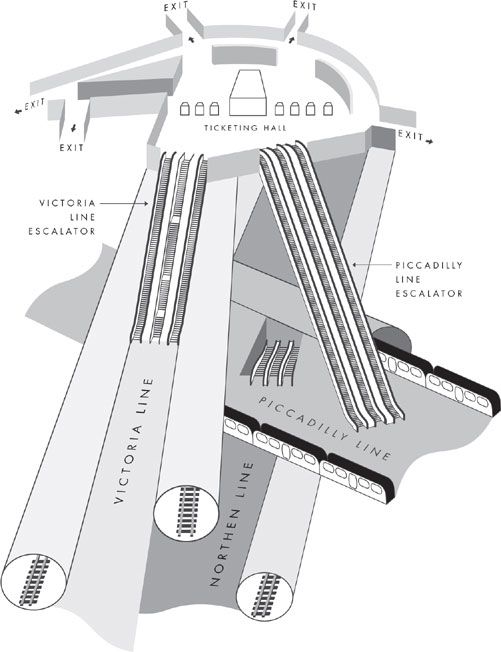

King’s Cross was one of the largest, grandest, and most heavily trafficked of London’s subway stops, a labyrinth of deep escalators, passageways, and tunnels, some of which were almost a century old. The station’s escalators, in particular, were famous for their size and age. Some stretched as many as five stories into the ground and were built of wooden slats and rubber handrails, the same materials used to construct them decades earlier. More than a quarter million passengers passed through King’s Cross every day on six different

train lines. During evening rush hour, the station’s ticketing hall was a sea of people hurrying beneath a ceiling repainted so many times that no one could recall its original hue.

The burning tissue, the passenger said, was at the bottom of one of the station’s longest escalators, servicing the Piccadilly line. Brickell immediately left his position, rode the escalator down to the platform, found the smoldering wad of tissue, and, with a rolled-up magazine, beat out the fire. Then he returned to his post.

Brickell didn’t investigate further. He didn’t try to figure out why the tissue was burning or if it might have flown off of a larger fire somewhere else within the station. He didn’t mention the incident to another employee or call the fire department. A separate department handled fire safety, and Brickell, in keeping with the strict divisions that ruled the Underground, knew better than to step on anyone’s toes. Besides, even if he

had

investigated the possibility of a fire, he wouldn’t have known what to do with any information he learned. The tightly prescribed chain of command at the Underground prohibited him from contacting another department without a superior’s direct authorization. And the Underground’s routines—handed down from employee to employee—told him that he should never, under any circumstances, refer out loud to

anything

inside a station as a “fire,” lest commuters become panicked. It wasn’t how things were done.

The Underground was governed by a sort of theoretical rule book that no one had ever seen or read—and that didn’t, in fact, exist except in the unwritten rules that shaped every employee’s life. For decades, the Underground had been run by the “Four Barons”—the chiefs of civil, signal, electrical, and mechanical engineering—and within each of their departments, there were bosses and subbosses who all jealously guarded their authority. The trains ran on time because all nineteen thousand Underground employees cooperated in a delicate system that passed passengers and trains among dozens—sometimes hundreds—of hands all day long. But that cooperation depended upon a balance of power between each of the four departments and all their lieutenants that, itself, relied upon thousands of habits that employees adhered to. These habits created a truce among the Four Barons and their deputies. And from that truce arose policies that told Brickell: Looking for fires isn’t your job. Don’t overstep your bounds.

“Even at the highest level, one director was unlikely to trespass on the territory of another,” an investigator would later note. “Thus,

the engineering director did not concern himself with whether the operating staff were properly trained in fire safety and evacuation procedures because he considered those matters to be the province of the Operations Directorate.”

So Brickell didn’t say anything about the burning tissue. In other circumstances, it might have been an unimportant detail. In this case, the tissue was a stray warning—a bit of fuel that had escaped from a larger, hidden blaze—that would show how perilous even perfectly balanced truces can become

if they aren’t designed just right.

6.29

Fifteen minutes after Brickell returned to his booth, another passenger noticed a wisp of smoke as he rode up the Piccadilly escalator; he mentioned it to an Underground employee. The King’s Cross safety inspector, Christopher Hayes, was eventually roused to investigate. A third passenger, seeing smoke and a glow from underneath the escalator’s stairs, hit an emergency stop button and began shouting at passengers to exit the escalator. A policeman saw a slight smoky haze inside the escalator’s long tunnel, and, halfway down, flames beginning to dart above the steps.

Yet the safety inspector, Hayes, didn’t call the London Fire Brigade. He hadn’t seen any smoke himself, and another of the Underground’s unwritten rules was that the fire department should never be contacted unless absolutely necessary. The policeman who had noticed the haze, however, figured he should contact headquarters. His radio didn’t work underground, so he walked up a long staircase into the outdoors and called his superiors, who eventually passed word to the fire department. At 7:36 p.m.—twenty-two minutes after Brickell was alerted to the flaming tissue—the fire brigade received a call: “Small fire at King’s Cross.” Commuters were pushing past the policeman as he stood outside, speaking on his radio. They were rushing into the station, down into the tunnels, focused on getting home for dinner.

Within minutes, many of them would be dead.

At 7:36

P.M.

, an Underground worker roped off entry to the Piccadilly escalator and another started diverting people to a different stairway. New trains were arriving every few minutes. The platforms where passengers exited subway cars were crowded. A bottleneck started building at the bottom of an open staircase.

Hayes, the safety inspector, went into a passageway that led to the Piccadilly escalator’s machine room. In the dark, there was a set of controls for a sprinkler system specifically designed to fight fires on escalators. It had been installed years earlier, after a fire in another station had led to a series of dire reports about the risks of a sudden blaze. More than two dozen studies and reprimands had said that the Underground was unprepared for fires, and that staff needed to be trained in how to use sprinklers and fire extinguishers, which were positioned on every train platform. Two years earlier the deputy assistant chief of the London Fire Brigade had written to the operations director for railways, complaining about subway workers’ safety habits.