The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business (30 page)

Read The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business Online

Authors: Charles Duhigg

Tags: #Psychology, #Organizational Behavior, #General, #Self-Help, #Social Psychology, #Personal Growth, #Business & Economics

Working at Target offered Pole a chance to study the most complicated of creatures—the American shopper—in its natural habitat. His job was to build mathematical models that could crawl through data and determine which households contained kids and which were dedicated bachelors; which shoppers loved the outdoors and who was more interested in ice cream and romance novels. Pole’s mandate was to become a mathematical mind reader, deciphering shoppers’ habits in order to convince them to spend more.

Then, one afternoon, a few of Pole’s colleagues from the marketing department stopped by his desk. They were trying to figure out which of Target’s customers were pregnant based on their buying patterns, they said. Pregnant women and new parents, after all, are the holy grail of retail. There is almost no more profitable, product-hungry, price-insensitive group in existence. It’s not just diapers and wipes. People with infants are so tired that they’ll buy everything they need—juice and toilet paper, socks and magazines—wherever they purchase their bottles and formula. What’s more, if a new parent starts shopping at Target, they’ll keep coming back for years.

Figuring out who was pregnant, in other words, could make Target millions of dollars.

Pole was intrigued. What better challenge for a statistical fortune-teller than not only getting inside shoppers’ minds, but their bedrooms?

By the time the project was done, Pole would learn some important lessons about the dangers of preying on people’s most intimate habits. He would learn, for example, that hiding what you know is sometimes as important as knowing it, and that not all women are enthusiastic about a computer program scrutinizing their reproductive plans.

Not everyone, it turns out, thinks mathematical mind reading is cool.

“I guess outsiders could say this is a little bit like Big Brother,” Pole told me. “That makes some people uncomfortable.”

Once upon a time, a company like Target would never have hired a guy like Andrew Pole. As little as twenty years ago retailers didn’t do this kind of intensely data-driven analysis. Instead, Target, as well as grocery stores, shopping malls, greeting card sellers, clothing retailers, and other firms, tried to peer inside consumers’ heads the old-fashioned way: by hiring psychologists who peddled vaguely scientific tactics they claimed could make customers spend more.

Some of those methods are still in use today. If you walk into a Walmart, Home Depot, or your local shopping center and look closely, you’ll see retailing tricks that have been around for decades, each designed to exploit your shopping subconscious.

Take, for instance, how you buy food.

Chances are, the first things you see upon entering your grocery store are fruits and vegetables arranged in attractive, bountiful piles. If you think about it, positioning produce at the front of a store doesn’t make much sense, because fruits and vegetables bruise easily at the bottom of a shopping cart; logically, they should be situated by the registers, so they come at the end of a trip. But as marketers and psychologists figured out long ago, if we

start

our shopping sprees by loading up on healthy stuff, we’re much more likely to buy Doritos, Oreos, and frozen pizza when we encounter them later on. The burst of subconscious virtuousness that comes from first buying butternut squash makes it easier to put a pint of ice cream in the cart later.

Or take the way most of us turn to the right after entering a store. (Did you know you turn right? It’s almost certain you do. There are thousands of hours of videotapes showing shoppers turning right once they clear the front doors.) As a result of this tendency, retailers fill the right side of the store with the most profitable products they’re hoping you’ll buy right off the bat. Or consider cereal and soups: When they’re shelved out of alphabetical order and seemingly at random, our instinct is to linger a bit longer and look at a

wider selection. So you’ll rarely find Raisin Bran next to Rice Chex. Instead, you’ll have to search the shelves for the cereal you want, and maybe get tempted to grab an extra box of another brand.

7.1

The problem with these tactics, however, is that they treat each shopper exactly the same. They’re fairly primitive, one-size-fits-all solutions for triggering buying habits.

In the past two decades, however, as the retail marketplace has become more and more competitive, chains such as Target began to understand they couldn’t rely on the same old bag of tricks. The only way to increase profits was to figure out each individual shopper’s habits and to market to people one by one, with personalized pitches designed to appeal to customers’ unique buying preferences.

In part, this realization came from a growing awareness of how powerfully habits influence almost every shopping decision. A series of experiments convinced marketers that if they managed to understand a particular shopper’s habits, they could get them

to buy almost anything.

7.2

One study tape-recorded consumers as they walked through grocery stores. Researchers wanted to know how people made buying decisions. In particular, they looked for shoppers who had come with shopping lists—who, theoretically, had decided ahead of time what they wanted to get.

What they discovered was that despite those lists, more than 50 percent of purchasing decisions occurred at the moment a customer saw a product on the shelf, because, despite shoppers’ best intentions, their habits were stronger than their written intentions. “Let’s see,” one shopper muttered to himself as he walked through a store. “Here are the chips. I will skip them. Wait a minute. Oh! The Lay’s

potato chips are on sale!” He put a bag in his cart.

7.3

Some shoppers bought the same brands, month after month, even if they admitted they didn’t like the product very much (“I’m not crazy about Folgers, but it’s what I buy, you know? What else is there?” one woman said as she stood in front of a shelf containing dozens of other coffee

brands). Shoppers bought roughly the same amount of food each time they went shopping, even if they had pledged to cut back.

“Consumers sometimes act like creatures of habit, automatically repeating past behavior with little regard to current goals,” two psychologists at the

University of Southern California wrote in 2009.

7.4

The surprising aspect of these studies, however, was that even though everyone relied on habits to guide their purchases, each person’s habits were different. The guy who liked potato chips bought a bag every time, but the Folgers woman never went down the potato chip aisle. There were people who bought milk whenever they shopped—even if they had plenty at home—and there were people who always purchased desserts when they said they were trying to lose weight. But the milk buyers and the dessert addicts didn’t usually overlap.

The habits were unique to each person.

Target wanted to take advantage of those individual quirks. But when millions of people walk through your doors every day, how do you keep track of their preferences and shopping patterns?

You collect data. Enormous, almost inconceivably large amounts of data.

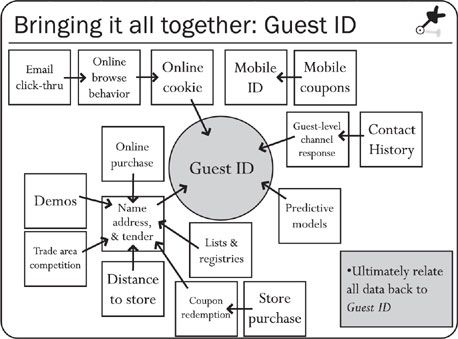

Starting a little over a decade ago, Target began building a vast data warehouse that assigned every shopper an identification code—known internally as the “Guest ID number”—that kept tabs on how each person shopped. When a customer used a Target-issued credit card, handed over a frequent-buyer tag at the register, redeemed a coupon that was mailed to their house, filled out a survey, mailed in a refund, phoned the customer help line, opened an email from Target, visited

Target.com

, or purchased anything online, the company’s computers took note. A record of each purchase was linked to that shopper’s Guest ID number along with information on everything else they’d ever bought.

Also linked to that Guest ID number was demographic information

that Target collected or purchased from other firms, including the shopper’s age, whether they were married and had kids, which part of town they lived in, how long it took them to drive to the store, an estimate of how much money they earned, if they’d moved recently, which websites they visited, the credit cards they carried in their wallet, and their home and mobile phone numbers. Target can purchase data that indicates a shopper’s ethnicity, their job history, what magazines they read, if they have ever declared bankruptcy, the year they bought (or lost) their house, where they went to college or graduate school, and whether they prefer certain brands of coffee, toilet paper, cereal, or applesauce.

There are data peddlers such as InfiniGraph that “listen” to shoppers’ online conversations on message boards and Internet forums, and track which products people mention favorably. A firm named Rapleaf sells information on shoppers’ political leanings, reading habits, charitable giving, the number of cars they own, and whether they prefer religious

news or deals on cigarettes.

7.5

Other companies analyze photos that consumers post online, cataloging if they are obese or skinny, short or tall, hairy or bald, and what kinds of products they might want to buy as a result. (Target, in a statement, declined to indicate what demographic companies it does business with and what kinds of information it studies.)

“It used to be that companies only knew what their customers

wanted

them to know,” said Tom Davenport, one of the leading researchers on how businesses use data and analytics. “That world is far behind us. You’d be shocked how much information is out there—and every company buys it, because it’s the only way to survive.”

If you use your Target credit card to purchase a box of Popsicles once a week, usually around 6:30 p.m. on a weekday, and megasized trash bags every July and October, Target’s statisticians and computer programs will determine that you have kids at home, tend to stop for groceries on your way back from work, and have a lawn that needs mowing in the summer and trees that drop leaves in the fall.

It will look at your other shopping patterns and notice that you sometimes buy cereal, but never purchase milk—which means that you must be buying it somewhere else. So Target will mail you coupons for 2 percent milk, as well as for chocolate sprinkles, school supplies, lawn furniture, rakes, and—since it’s likely you’ll want to relax after a long day at work—beer. The company will guess what you habitually buy, and then try to convince you to get it at Target. The firm has the capacity to personalize the ads and coupons it sends to every customer, even though you’ll probably never realize you’ve received a different flyer in the mail than your neighbors.

“With the Guest ID, we have your name, address, and tender, we know you’ve got a Target Visa, a debit card, and we can tie that to your store purchases,” Pole told an audience of retail statisticians at a conference in 2010. The company can link about half of all in-store sales to a specific person, almost all online sales, and about a quarter of online browsing.

At that conference,

Pole flashed a slide showing a sample of the data Target collects, a diagram that caused someone in the audience to whistle in wonder when it appeared on the screen:

7.6

The problem with all this data, however, is that it’s meaningless without statisticians to make sense of it. To a layperson, two shoppers who both buy orange juice look the same. It requires a special kind of mathematician to figure out that one of them is a thirty-four-year-old woman purchasing juice for her kids (and thus might appreciate a coupon for a Thomas the Tank Engine DVD) and the other is a twenty-eight-year-old bachelor who drinks juice after going for a run (and thus might respond to discounts on sneakers). Pole and the fifty other members of Target’s Guest Data and Analytical Services department were the ones who found the habits hidden in the facts.

“We call it the ‘guest portrait,’ ” Pole told me. “The more I know about someone, the better I can guess their buying patterns. I’m not going to guess everything about you every time, but I’ll be right more often than I’m wrong.”

By the time Pole joined Target in 2002, the analytics department had already built computer programs to identify households containing children and, come each November, send their parents catalogs of bicycles and scooters that would look perfect under the Christmas tree, as well as coupons for school supplies in September and advertisements for pool toys in June. The computers looked for shoppers buying bikinis in April, and sent them coupons for sunscreen in July and weight-loss books in December. If it wanted, Target could send each customer a coupon book filled with discounts for products they were fairly certain the shoppers were going to buy, because they had already purchased those exact items before.