The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business (32 page)

Read The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business Online

Authors: Charles Duhigg

Tags: #Psychology, #Organizational Behavior, #General, #Self-Help, #Social Psychology, #Personal Growth, #Business & Economics

That certainty wasn’t based solely on intuition. At the time, the record business was undergoing a transformation similar to the data-driven shifts occurring at Target and elsewhere. Just as retailers were using computer algorithms to forecast shoppers’ habits, music and radio executives were using computer programs to forecast listeners’ habits. A company named Polyphonic HMI—a collection of artificial intelligence experts and statisticians based in Spain—had created a program called Hit Song Science that analyzed the mathematical characteristics of a tune and predicted its popularity. By comparing the tempo, pitch, melody, chord progression, and other factors of a particular song against the thousands of hits stored in Polyphonic HMI’s database, Hit Song Science could deliver a score that

forecasted if a tune was likely to succeed.

7.14

The program had predicted that Norah Jones’s

Come Away with

Me,

for instance, would be a hit after most of the industry had dismissed the album. (It went on to sell ten million copies and win eight Grammys.) It had predicted that “Why Don’t You and I” by Santana would be popular, despite DJs’ doubts. (It reached number three on the

Billboard

Top 40 list.)

When executives at radio stations ran “Hey Ya!” through Hit Song Science, it did well. In fact, it did better than well: The score was among the highest anyone had ever seen.

“Hey Ya!,” according to the algorithm, was going to be a monster hit.

On September 4, 2003, in the prominent slot of 7:15 p.m., the Top 40 station WIOQ in Philadelphia started playing “Hey Ya!” on the radio. It aired the song seven more times that week, and a total of

thirty-seven times throughout the month.

7.15

At the time, a company named Arbitron was testing a new technology

that made it possible to figure out how many people were listening to a particular radio station at a given moment, and how many switched channels during a specific song. WIOQ was one of the stations included in the test. The station’s executives were certain “Hey Ya!” would keep listeners glued to their radios.

Then the data came back.

Listeners didn’t just dislike “Hey Ya!” They hated it according to the data.

7.16

They hated it so much that nearly a third of them changed the station within the first thirty seconds of the song. It wasn’t only at WIOQ, either. Across the nation, at radio stations in Chicago, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Seattle, whenever “Hey Ya!” came on, huge numbers of listeners would click off.

“I thought it was a great song the first time I heard it,” said John Garabedian, the host of a syndicated Top 40 radio show heard by more than two million people each weekend. “But it didn’t sound like other songs, and so some people went nuts when it came on. One guy told me it was the worst thing he had ever heard.

“People listen to Top 40 because they want to hear their favorite songs or songs that sound just like their favorite songs. When something different comes on, they’re offended. They don’t want anything unfamiliar.”

Arista had spent a lot of money promoting “Hey Ya!” The music and radio industries needed it to be a success. Hit songs are worth a fortune—not only because people buy the song itself, but also because a hit can convince listeners to abandon video games and the Internet for radio. A hit can sell sports cars on television and clothing inside trendy stores. Hit songs are at the root of dozens of spending habits that advertisers, TV stations, bars, dance clubs—even technology firms such as Apple—rely on.

Now, one of the most highly anticipated songs—a tune that the algorithms had predicted would become the song of the year—was flailing. Radio executives were desperate to find something that would

make “Hey Ya!” into a hit.

7.17

That question—how do you make a song into a hit?—has been puzzling the music industry ever since it began, but it’s only in the past few decades that people have tried to arrive at scientific answers. One of the pioneers was a onetime station manager named Rich Meyer who, in 1985, with his wife, Nancy, started a company called Mediabase in the basement of their Chicago home. They would wake up every morning, pick up a package of tapes of stations that had been recorded the previous day in various cities, and count and analyze every song that had been played. Meyer would then publish a weekly newsletter tracking which tunes were rising or declining in popularity.

In his first few years, the newsletter had only about a hundred subscribers, and Meyer and his wife struggled to keep the company afloat. However, as more and more stations began using Meyer’s insights to increase their audiences—and, in particular, studying the formulas he devised to explain listening trends—his newsletter, the data sold by Mediabase, and then similar services provided by a growing industry of data-focused consultants, overhauled how radio stations were run.

One of the puzzles Meyer most loved was figuring out why, during some songs, listeners never seemed to change the radio dial. Among DJs, these songs are known as “sticky.” Meyer had tracked hundreds of sticky songs over the years, trying to divine the principles that made them popular. His office was filled with charts and graphs plotting the characteristics of various sticky songs. Meyer was always looking for new ways to measure stickiness, and about the time “Hey Ya!” was released, he started experimenting with data from the tests that Arbitron was conducting to see if it provided any fresh insights.

Some of the stickiest songs at the time were sticky for obvious

reasons—“Crazy in Love” by Beyoncé and “Señorita” by Justin Timberlake, for instance, had just been released and were already hugely popular, but those were great songs by established stars, so the stickiness made sense. Other songs, though, were sticky for reasons no one could really understand. For instance, when stations played “Breathe” by Blu Cantrell during the summer of 2003, almost no one changed the dial. The song is an eminently forgettable, beat-driven tune that DJs found so bland that most of them only played it reluctantly, they told music publications. But for some reason, whenever it came on the radio, people listened, even if, as pollsters later discovered, those same listeners said they didn’t like the song very much. Or consider “Here Without You” by 3 Doors Down, or almost any song by the group Maroon 5. Those bands are so featureless that critics and listeners created a new music category—“bath rock”—to describe their tepid sounds. Yet whenever they came on the radio, almost no one changed the station.

Then there were songs that listeners said they actively

disliked,

but were sticky nonetheless. Take Christina Aguilera or Celine Dion. In survey after survey, male listeners said they hated Celine Dion and couldn’t stand her songs. But whenever a Dion tune came on the radio, men stayed tuned in. Within the Los Angeles market, stations that regularly played Dion at the end of each hour—when the number of listeners was measured—could reliably boost their audience by as much as 3 percent, a huge figure in the radio world. Male listeners may have

thought

they disliked Dion, but when her songs played,

they stayed glued.

7.18

One night, Meyer sat down and started listening to a bunch of sticky songs in a row, one right after the other, over and over again. As he did, he started to notice a similarity among them. It wasn’t that the songs sounded alike. Some of them were ballads, others were pop tunes. However, they all seemed similar in that each sounded exactly like what Meyer expected to hear from that particular genre. They

sounded

familiar

—like everything else on the radio—but a little more polished, a bit closer to the golden mean of the perfect song.

“Sometimes stations will do research by calling listeners on the phone, and play a snippet of a song, and listeners will say, ‘I’ve heard that a million times. I’m totally tired of it,’ ” Meyer told me. “But when it comes on the radio, your subconscious says, ‘I know this song! I’ve heard it a million times! I can sing along!’ Sticky songs are what you

expect

to hear on the radio. Your brain secretly wants that song, because it’s so familiar to everything else you’ve already heard and liked. It just sounds right.”

There is evidence that a preference for things that sound “familiar” is a product of our neurology. Scientists have examined people’s brains as they listen to music, and have tracked which neural regions are involved in comprehending aural stimuli. Listening to music activates numerous areas of the brain, including the auditory cortex, the thalamus, and

the superior parietal cortex.

7.19

These same areas are also associated with pattern recognition and helping the brain decide which inputs to pay attention to and which to ignore. The areas that process music, in other words, are designed to seek out patterns and look for familiarity. This makes sense. Music, after all, is complicated. The numerous tones, pitches, overlapping melodies, and competing sounds inside almost any song—or anyone speaking on a busy street, for that matter—are so overwhelming that, without our brain’s ability to focus on some sounds and ignore others, everything would seem like

a cacophony of noise.

7.20

Our brains crave familiarity in music because familiarity is how we manage to hear without becoming distracted by all the sound. Just as the scientists at MIT discovered that behavioral habits prevent us from becoming overwhelmed by the endless decisions we would otherwise have to make each day, listening habits exist because, without them, it would be impossible to determine if we should concentrate on our child’s voice, the coach’s whistle, or the noise from a busy street during a Saturday soccer game. Listening

habits allow us to unconsciously separate important noises from those that can be ignored.

That’s why songs that sound “familiar”—even if you’ve never heard them before—are sticky. Our brains are designed to prefer auditory patterns that seem similar to what we’ve already heard. When Celine Dion releases a new song—and it sounds like every other song she’s sung, as well as most of the other songs on the radio—our brains unconsciously crave its recognizability and the song becomes sticky. You might never attend a Celine Dion concert, but you’ll listen to her songs on the radio, because that’s what you

expect

to hear as you drive to work. Those songs correspond perfectly to your habits.

This insight helped explain why “Hey Ya!” was failing on the radio, despite the fact that Hit Song Science and music executives were sure it would be a hit. The problem wasn’t that “Hey Ya!” was bad. The problem was that “Hey Ya!”

wasn’t familiar

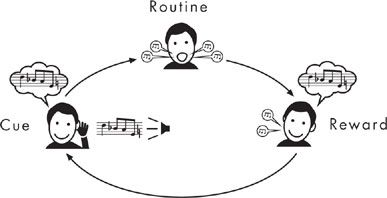

. Radio listeners didn’t want to make a conscious decision each time they were presented with a new song. Instead, their brains wanted to follow a habit. Much of the time, we don’t actually choose if we like or dislike a song. It would take too much mental effort. Instead, we react to the cues (“This sounds like all the other songs I’ve ever liked”) and rewards (“It’s fun to hum along!”) and without thinking, we either start singing, or reach over and change the station.

THE FAMILIARITY LOOP

In a sense, Arista and radio DJs faced a variation of the problem Andrew Pole was confronting at Target. Listeners are happy to sit through a song they might say they dislike, as long as it seems like something they’ve heard before. Pregnant women are happy to use coupons they receive in the mail, unless those coupons make it obvious that Target is spying into their wombs, which is unfamiliar and kind of creepy. Getting a coupon that makes it clear Target knows you’re pregnant is at odds from what a customer expects. It’s like telling a forty-two-year-old investment banker that he sang along to Celine Dion. It just feels wrong.

So how do DJs convince listeners to stick with songs such as “Hey Ya!” long enough for them to become familiar? How does Target convince pregnant women to use diaper coupons without creeping them out?

By dressing something new in old clothes, and making the unfamiliar seem familiar.