The Rising Tide: A Novel of World War II (56 page)

Read The Rising Tide: A Novel of World War II Online

Authors: Jeff Shaara

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #War & Military, #Action & Adventure

He faced one of those choices now, watched as the single plane touched down, could only wait patiently as the pilot taxied toward the tarmac. In a few seconds the motors were shut down, the props slowing, and quickly the door at the tail of the plane opened. Eisenhower moved that way, his aides gathering a short distance behind. He saw a face, a young officer, unfamiliar, the man stepping down quickly, a sharp salute. Eisenhower returned it, waited, saw another face, older, the uniform perfect, the three stars on the man’s shoulder catching the sunlight. The promotion to lieutenant general had come only weeks before, no one questioning, no jealousy, none of the intrigue and backbiting that suggested a man had not earned the rank. Eisenhower couldn’t help but smile, returned the man’s salute. It was Omar Bradley.

T

hey walked along the shore, and Eisenhower stared out to the open water, one British destroyer at anchor. It was Cunningham’s precaution, that with Eisenhower’s advance headquarters at the seaside town, there was always danger from a surprise attack by German dive-bombers or commandos, the Luftwaffe still launching the occasional raid.

“I don’t believe this, Ike. How can this be?”

“Believe it. Marshall has already approved your transfer.”

Bradley walked in silence, and Eisenhower was surprised by the man’s lack of enthusiasm. “Is there something you don’t understand?”

Bradley stopped, turned toward Eisenhower, put his hands on his hips. “I don’t understand why Marshall or anyone else would pick me for the job.”

Eisenhower could see it now, it wasn’t just humility. Bradley seemed genuinely concerned.

“Brad, the job is yours, unless you can give me a damned good reason why we should pick someone else.” He paused, waited, Bradley silent. “Good. You’re the man for the job. As soon as you can get your ducks in a row here, you will report to General Devers in London and assume command of the First Army. You will establish headquarters at Bristol, most likely. Even though by title Jake Devers commands American forces in the European theater, make no mistake about this, Brad. I don’t expect Devers to lead troops in the field. It’s just not his strength. Your command will eventually spearhead our role in Overlord.”

Bradley began to walk again, rubbed his hands together. “I understand. Who’s replacing me at Second Corps?”

“John Lucas.”

Bradley nodded, and Eisenhower could see the man’s mind at work, already digesting, absorbing everything that might lie in front of him. He looked at Eisenhower now, a slight squint in his eyes.

“You’re telling me I’m being promoted to army commander. That’s a hell of a pat on the back. I’m not sure how to react to that. I’ll give it everything I can, but, Ike…something doesn’t feel right. How is this going to sit…”

“With Patton?”

“Yeah. With Patton. This ought to be his command, Ike. He outranks me. You’re shoving me up the ladder right past him.”

Eisenhower said nothing, kicked at the hard sand with his boot, dislodged a round, white rock, kicked it toward the water. Bradley started to speak, and Eisenhower held up a hand.

“You know George as well as anyone. Do I have to explain it to you?”

“You mean…it’s all about the slapping incident?”

“That’s part of it. I shouldn’t have to spell it out for you, Brad. This operation is going to involve some pretty intensive training, some pretty tough coordination with the Brits. Chances are Monty will be involved in a big way, and I haven’t been told yet who will command the overall operation. I don’t think the decision’s been made. But be honest with me. Do you think George is the right man to command something this complicated?”

“I can’t answer that, Ike. George is the best ass-kicker in the army.”

“Well, I can. The job is yours. We don’t always need ass-kickers, Brad. You know damned well that some of Patton’s subordinates don’t agree with his style of doing things.” Eisenhower paused, wondered if Bradley would open up to him. He knew that Bradley had been concerned that Patton’s infatuation with Messina might get more of Bradley’s people killed than the prize was worth. “I want that honesty, Brad.”

“He has his ways, Ike. Usually it works. You can’t argue with success.”

“To hell with that.”

Bradley stopped again, stared out toward the British ship.

“All that razzle-dazzle looks good on magazine covers. But I heard it from the men, Ike, after those parades that George would lead through the troops, all those clean uniforms, the flags and sirens. It didn’t always go over well. My boys were fighting the toughest enemy we’ve ever faced, on ground more difficult than anything in Africa. Then George would come through with his sirens blaring and expect them to cheer. They did, some of them. But not everybody. When he belted that kid…there were people on my own staff who wanted to see him strung up.” Bradley paused, and Eisenhower could see the man searching for words. “I heard all this stuff about Rommel, how he won battles because he was out there with his men. I don’t know how much of that is true, how much is German baloney. If Rommel seemed to be one of his men, if he seemed to feel what they were feeling, if he was willing to pick up a rifle or climb into a tank, sure, I can understand how that would pick his men up. But that’s not what George does. If we still had plumes in our hats, he’d have the biggest one. If we rode horses, he’d have the white one. Dammit, Ike, don’t misunderstand me. There may be no better tactical officer in this army than George Patton. Nobody knows how to maneuver troops under fire like he does. Audacity, Ike. That’s what it is. Every army needs a Stonewall Jackson once in a while. But Jackson’s uniform wasn’t spotless, he didn’t have a polished helmet, and if he’d carried pearl-handled pistols, he’d have fired them at the enemy once in a while.” He stopped, looked down. “My apologies, Ike. I spoke too freely.”

“I told you to be honest. I can’t disagree with one thing you’ve said. But right now, George isn’t your concern. I don’t know how he’ll respond to your transfer, but I can’t worry about that now. I have my hands full right here. Marshall wants you in England, and the sooner the better. I’m already getting orders to prepare combat units to follow you there, and they need to begin training as soon as the bases are set up. You’re in command up there, Brad. There’s nobody in this army I’d rather see at the wheel.”

40. ADAMS

T

hey had been pulled out of Sicily on August 20, the entire Eighty-second Airborne Division reestablished around the airfields at Kairouan, Tunisia. Almost immediately, the recruits had come, the new men to fill the depleted ranks. With the new men came new training, and the jumps continued. As they had done so many times before, Adams and the other jumpmasters manned the doorways of the C-47s, coaching and prodding the unfamiliar faces, insuring that when they jumped into a combat zone, they would know that the bone-jarring landings would be no different from what they had practiced so often at Fort Benning. Of course, no amount of additional training could predict how a man might actually respond when he jumped into the middle of an enemy machine-gun nest.

Unlike their first encampment in North Africa, this time the misery and boredom did not continue for more than a few days. By early September, they were sent back to Sicily, the airbase at Licata, on the southern coast, and the men in charge began ironing out the problems that had plagued the 505th’s first jump. Homing beacons and portable radio sets were old technology, but no one in the Airborne command had seemed to consider that this sort of communications was an absolute necessity in the field. After Sicily, they changed their minds, energized by the pilots, who pushed their officers to find better ways to guide them to their drop zones. The Airborne’s drop into Sicily had been extraordinarily valuable, blocking the German advance, which might have saved the entire operation. But most of the Allied commanders, including Eisenhower, considered that to be a fortunate accident. No matter how effective the men of the Eighty-second had been in Sicily, their jump had been a chaotic mess. Criticism of the paratroopers had come from all directions, rumors filtering down that the Eighty-second might be disbanded, or redesignated as infantry. Like most such rumors, Adams knew that such a radical change was unlikely to happen, but with Eisenhower himself voicing serious doubts about the effectiveness of the paratroop force, the officers were taking the rumors seriously. General Ridgway responded vigorously to Eisenhower’s criticisms and had ordered that steps be taken to insure that future jump missions be equipped with the tools necessary so that regiments actually landed on their designated drop zones.

At Licata, some of the men had been organized into smaller units, trained for a specific job. They were called pathfinders, paratroopers whose job would be to land twenty to thirty minutes before the main body, to set up small radio transmitters that would guide the pilots to the proper jump zones. Besides the radios, some of the pathfinders would carry a krypton light, a small beacon that emitted a single blinding flash of light visible miles away. If all that failed, the pathfinders were taught that once they heard the C-47s, they could simply light a fire in the shape of a

T,

which would clearly designate the landing zone. How exactly the pathfinders would find the correct zones themselves was not revealed to men like Adams. His faith in the pathfinders was as limited as his faith that some officer would come up with any gimmick designed to make a soldier’s life simpler. His men agreed, most of them convinced that it was still up to the pilots. If the men in the cockpit got lost, there wasn’t much anyone on the ground could do about it.

LICATA FIELD, SICILY—SEPTEMBER 8, 1943

He sat beneath the wing of a C-47, double-checking his pack, killing time, the men around him waiting as he was, nothing else to do until the orders came to board the planes. There was little talking, even the new men subdued, their nervous chatter held down, each man locked into his own thoughts.

He counted his ration tins, far fewer than he had carried on Sicily. Their personal gear had been pared down, blankets, toilet articles, and extra clothing reduced to a minimum, or eliminated altogether. It was one valuable lesson from the jumps in Sicily: armament had far more value in the field than personal convenience. The Sicilian countryside had offered them all the comforts a man required to survive. What they could not replace were the weapons, the grenades and explosives, parts for the heavy machine guns. At Fort Benning, the men had practiced by dropping their heavy equipment separately, in bundles attached beneath the wings of the C-47s. But Sicily was not Fort Benning, and the men had learned that stumbling around in the dark searching for lost bundles was a surefire way to attract the enemy’s attention. More often the bundles were simply lost, many of them still scattered in the rough hills and thickets that spread across southern Sicily. If the men wanted use of a heavy machine gun or a bazooka, they would find a way to carry one with them.

Adams counted his grenades again, glanced up at the others, saw each man following his example. His platoon had only a few new faces, none of them yet showing him the telltale signs of becoming a weak link. They had responded well to the training, had made two night jumps around Kairouan, with no disasters. Now, they sat close to the rows of planes, trying to keep out of the way of the maintenance crews, while they waited for the officers to give them the order.

Scofield had been gone for some time, long meetings with the other officers, Adams glancing up every few seconds toward the low block building at the far end of the tarmac. He saw the captain now, others, pouring out of the building in a rush, moving quickly.

Adams’s heart jumped, and he called out, “Here we go! Ready packs. Prepare to board up!”

Scofield was jogging toward them, waved his hands in the air, shouted, “Stand down! The mission’s been scrapped!”

Scofield motioned to the men to gather, was clearly angry. The entire company moved close, and Scofield paced in small, quick steps, a tight circle, his arms waving like the wings of a deranged bird.

“Dammit! Second time in a week! Brass can’t make up its mind what the hell to do with us! We’re not going anywhere today! Giant Two has now been scratched. Just like Giant One. They make a plan, get us all fired up to go, and then some general chickens out!”

“Why, Captain?”

The voice came from behind Adams, one of the new men, Unger, the high-pitched voice of a child. Scofield looked at the young man, seemed to calm, gather himself. Adams could see that Scofield was scolding himself, thought, easy, Captain. Officers aren’t supposed to gripe about generals, especially not to pimple-faced enlisted men.

“Never mind. All you need to know is we’ve been ordered to stand down. Colonel Gavin got the word from General Ridgway. Those orders came from higher up. The colonel didn’t tell me any more than I’m going to tell you, so no questions. It’s no secret anymore, so I can tell you that Giant Two was a drop on the airfields around Rome. We were supposed to land right on the fields, and the Eyeties were going to be there to help us. They had agreed to supply everything we would need to capture the landing strips and secure them against any German units in the area. They were supposed to help us out by blowing up bridges, taking out German antiaircraft batteries, and once we hit the ground, they would furnish us with a considerable amount of supplies. Apparently, General Ridgway had some concerns about this and questioned whether or not the Italians could actually deliver what they promised. It seems someone above him shared those concerns. Count your stars, gentlemen. We might have jumped right into a massacre.”

Adams had crawled out from under the wing, stood, said, “So, what now, sir?”

Scofield put his hands on his hips, shook his head. “We remain on high alert. The Five-oh-five isn’t the first team on this one anyway. The 504th and the 509th will take the point on any new orders. We did our part in Sicily, and so, they’re figuring we can hang back as the reserve. But don’t any of you think we’re on vacation. They might call for us at any time. Seems like this operation is already

fumtu.

As much confusion as there’s been already…” Scofield stopped. “Check that. Just keep yourself ready to go. Get some sleep. Eat something. We get a call from General Ridgway, we might need to be up at it pretty quickly.”

Scofield moved away, and Adams slid back under the wing, gathered his gear. The others were talking, low grumbles, mostly the new men, and he ignored them, thought, don’t be in such a damned hurry to get your ass shot off.

“Sarge?”

The voice was unmistakable, and he turned. “What is it, Unger?”

“The captain said this operation is

fumtu

. What the heck does that mean?”

Adams laughed. “You should already know, Private, that in this army, there’s

snafu

and there’s

fumtu

.”

Unger stared at him, empty expression.

“You a churchman, right, Unger?”

“Yes, sir. Every Sunday.”

“All right, I’ll give you the clean translation.

Situation Normal All Fouled Up

. But what the captain was telling you is, this operation is

Fouled Up More Than Usual

.”

T

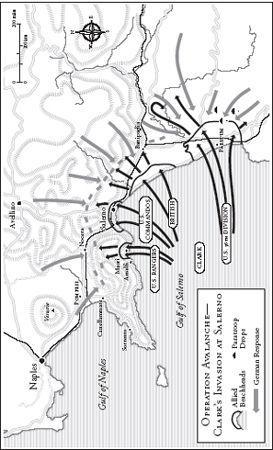

he Fifth Army’s landings at Salerno began at 3:30 a.m., September 9, four divisions, two American and two British, supplemented by American rangers and commandos. To the north, the town of Salerno fell easily into American hands, but in the center, the British forces confronted heavy resistance from German defenders in the heights above the beaches. After a long day of difficult fighting, the British finally secured their beachhead, aided considerably by firepower from the naval artillery offshore. On the right flank of the landings, the American Sixth Corps, under Ernest Dawley, pushed only into light resistance and had, by nightfall on September 9, accomplished most of its objectives. With the landings complete, General Clark had every reason to believe that Avalanche was off and running.

Kesselring’s reinforcements were quickly summoned, and within hours of the landings, German panzer units were surging toward Clark’s beachheads. In the center of the beachhead, the Sele River flowed into the Gulf of Salerno, and along the mouth of the river, sandbars had formed, preventing the landing craft from putting troops near the river itself. The result was a gap, several miles wide, between the British troops in the center and Dawley’s corps on the right. On September 10, Dawley still believed he had the upper hand in his sector, and he chose the Thirty-sixth Division to make the hardest push inland, seeking to capture roads, hilltops, and key intersections. The Thirty-sixth had yet to be tested in battle, but with little opposition, they had made good progress and accomplished most of Dawley’s objectives, extending the beachhead far inland. What Dawley did not realize was that to his left, Kesselring’s panzers were driving toward the beach and were already beginning to fill the gap. When the Germans launched their counterattacks, Dawley’s men found themselves dangerously flanked and were soon virtually cut off. Along both sides of the gap, the Allied positions were now engulfed by German armor, and on the right, the green soldiers of the Thirty-sixth began to crack. Over the next three days, Clark’s initial successes were erased by the German assaults, and the Allied beachheads began to crumble, panicked troops falling back toward the beaches, protected only by the umbrella of fire from the naval artillery.

On September 13, Clark sent Matthew Ridgway a desperate plea for assistance, and Ridgway responded immediately. That night, Colonel Reuben Tucker’s 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment made the Eighty-second Airborne’s first drop into Italy, a desperate attempt to fill the wide gap in the Allied lines and bolster the battered Thirty-sixth Division. The following day, the 509th, under Colonel Edson Raff received orders to jump as well. The 509th had been the first wave of Operation Torch, had begun the Allied invasion of North Africa by being dropped haphazardly across two hundred miles of desert. Throughout the Sicilian campaign, the men of the 509th had impatiently stewed in North Africa, while the 504th and 505th did the work. Now, Clark ordered the 509th to make the Airborne’s most dangerous jump. They would attempt to secure a critical crossroads near the village of Avellino, far inland, and far into enemy territory, to prevent any more German reinforcements from reaching the already reeling Allied troops. If the 509th was to survive at all, they would have to hold on until someone from Clark’s Fifth Army reached their position. If the Germans succeeded in driving Clark’s forces back into the sea, the 509th would simply be swallowed up.

On September 14, the men of Jim Gavin’s 505th stayed close to the planes, wondering if they would be used at all. By midafternoon the questions were answered. Gavin learned they were not to be held back as reserves after all.

LICATA AIRFIELD—SEPTEMBER 14, 1943

They had camped among the olive groves, broad fields of ancient trees. Except for the wings of the C-47s, the olive trees were the only shade within reach, the only place a man could rest without baking in the sun.

Adams had slept, lying on his back, his helmet on his face, sweat soaking his clothes, a soft breeze cooling him. He was awake now, stretched his legs, raised the helmet slightly, glanced at his watch. Three o’clock, he thought. If something’s gonna happen, it better happen quick. He heard voices, the sound of a man choking. There was laughter, and Adams knew the routine, pulled the helmet away, blinked through the sunlight. He saw Unger, the young man on his knees, red-faced, spitting furiously, scratching at his belt, trying to grab his canteen. Adams slammed the helmet on his head, rolled to one side, pushed himself to his feet. He was already angry, slapped at the dirt on his pant legs, had gone through this routine too many times.