The Secret Lives of Hoarders: True Stories of Tackling Extreme Clutter (2 page)

Read The Secret Lives of Hoarders: True Stories of Tackling Extreme Clutter Online

Authors: Matt Paxton,Phaedra Hise

Tags: #General, #United States, #Psychology, #Case Studies, #Psychopathology, #Compulsive Behavior, #Compulsive Hoarding - United States, #Compulsive Hoarding, #Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

BOOK: The Secret Lives of Hoarders: True Stories of Tackling Extreme Clutter

8.42Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

That struck a chord with me because I knew a little bit about unhappiness, tragedy, and addiction. I had spent a few months working for a large casino in Lake Tahoe in 1999, and while I was there I fell in love with gambling. It became a full-blown addiction, so bad that at one point I found myself $40,000 in debt. When I couldn't pay my bookie, he broke my nose and I had to leave town.

I eventually paid back my debt and I haven't gambled since, but I know what it feels like to be lonely and miserable, and to turn to something that feels good at the moment but is ultimately destructive. Timothy's situation felt more than a little familiar to me and I found myself wishing I could have met the guy and talked with him about it.

With the estate sale completed and after a final cleanup of what was left behind, I started looking for another messy house to clean.

The second job was referred to me by a social worker in a nearby county. She had a case in which a woman in her mid-forties, Aimee, was living in a terrible state of squalor. She was all but confined to her bed, where she slept, ate, and went to the bathroom by leaning off the side of the mattress. The place had been officially condemned by the county, and since there was some funding to clean it up, the social worker, who had seen a copy of my flyer that said no case was too extreme, called us in. She did give us fair warning that it would really test the limits of our claim. And she was right: The whole place stank from rotting food, urine, and feces. During our first visit to Aimee's house, the social worker gave us the background on this caseâand it was the first time I heard the word “hoarder.”

I went home and started researching hoarding. The disorder was fascinating because I could relate to a lot of the feelings and experiences that a hoarder goes through. I knew I could really help these people in need.

As my two buddies and I cleaned her house, we talked with Aimee, asking about her life. She admitted that she had rejected everyone because of her hoarding. Although she didn't want us in her home, she was happy to know that someone was interested in her story, and I wanted to find out more about herâand about the phenomenon of hoarding.

Since Aimee, I've had hundreds of hoarding clients, ranging from people who just have a cluttered garage that they want to get under control, to those with entire houses overflowing with trash, feces, animals (alive and dead), and vermin.

I didn't set out to be an extreme cleaning specialist. What hooked me was learning that hoarders are people with serious issues, and that only a few of their life decisions or events separate me from them. What if I hadn't been able to pay back my bookie? What if he had broken more than my nose? What if my friend hadn't loaned me his couch for a few months when I was down on my luck? I could have ended up like any of the clients I work with, or worse.

I have learned that hoarders don't love the way they live. I see them struggling to clean up but just not having the means or the willpower to get it done. Maybe their families don't understand them, or perhaps they have an untreated mental illness that blocks the path to staying clean.

After years of working with hoarders, I've figured out how to make sense of their world because I understand the hard times they've experienced. I can get them talking about their issues and help them straighten out their housesâand their lives. I'm not a therapist, but I work closely with experienced psychologists like Dr. Suzanne Chabaud, who specializes in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and hoarding at her clinic in New Orleans; Dr. Robin Zasio, who runs the Compulsive Hoarding Center in Sacramento, California; Dr. Lisa Hale, who heads the Kansas City Center for Anxiety Treatment; Dr. Renae Reinardy, head of the Lakeside Center for Behavioral Change in Fargo, North Dakota; and Dr. Elizabeth Moore and other specialists at the Institute of Living in Hartford, Connecticut.

The bottom line is that hoarders are good people who are struggling with difficult issues. To move toward recovery they need love and help, not ridicule. That doesn't mean we don't talk about their issues. Hoarders aren't stupid, and they know that what they are doing is a problem. But threatening, bullying, and issuing ultimatums aren't going to prod them to clean up. They want to de-clutter, but they can't unless they have encouragement and support.

I've worked with hoarders living in houses filled with rotting food and dog feces, and hoarders living with dozens of animals running all over the house. I've helped hoarders let go of their beloved collections of handbags, handguns, and dead rats. The truth is that some recover, and some don't. Hoarding is a serious mental illness, and sometimes “recovery” is a relative term. But I have learned what the challenges are and how to address them. I have seen what the critical elements of success are for any hoarder, and how those elements can combine to give a hoarder the best chance at de-cluttering.

I can help families and others working with hoarders maximize the hoarder's chances for getting and staying clean. It's a long and arduous process, and I will explain how to stay patient and positive for the months, and sometimes years, that it takes.

The key is hope. As long as everyone involved believes that the hoarder's life can get better, it truly can.

Because some of the stories I tell in this book are deeply personal, I have changed the names and identifying details. Some are composites, but all of the stories are true.

1

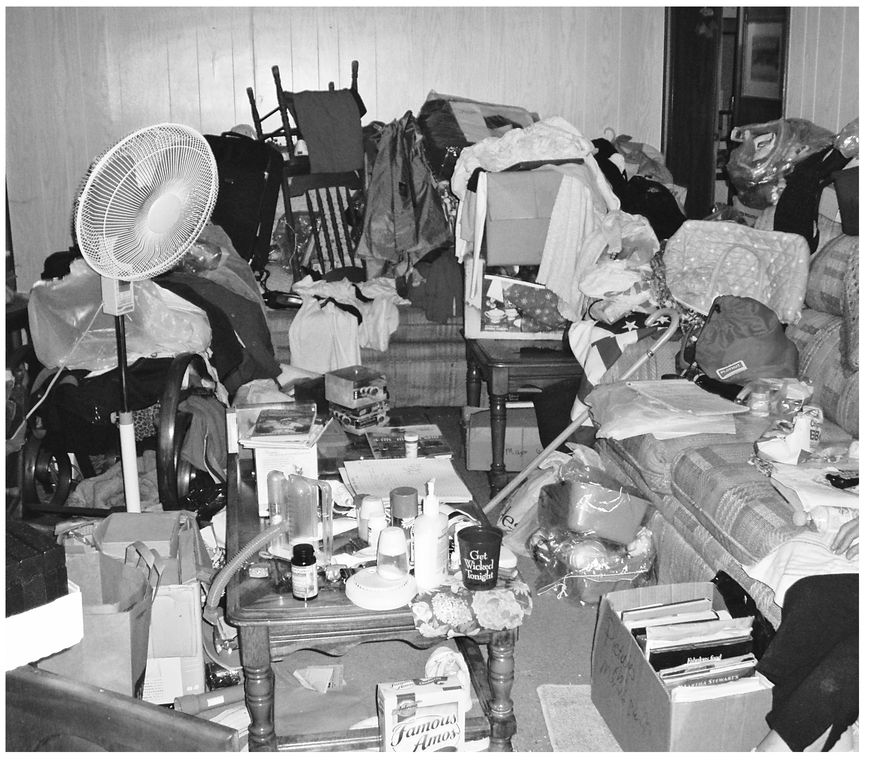

WHAT IS HOARDING?

M

argaret is a classic, stereotypical hoarder who had clearly given up years ago. Living in a threebedroom, double-wide trailer home in rural Idaho with too many dogs to count, she had been without electricity or running water for years. The floors were damp with brown muck. Decomposing trash was piled up to five feet high, through which narrow walkways gave limited access to each room.

argaret is a classic, stereotypical hoarder who had clearly given up years ago. Living in a threebedroom, double-wide trailer home in rural Idaho with too many dogs to count, she had been without electricity or running water for years. The floors were damp with brown muck. Decomposing trash was piled up to five feet high, through which narrow walkways gave limited access to each room.

In the kitchen, flies swarmed the windows and clung dying to a strip of flypaper hanging over the sink. None of the appliances worked except for one microwave that had been stacked on top of a broken one. All of the appliances and cabinets were smeared with unidentifiable black and orange gunk. Dust and cobwebs covered the walls and hung from the ceiling. The bathrooms were just as bad. A bucket of murky water sat next to the toilet, to pour into it for flushing.

The dogs had clawed and chewed away the bottom half of each bedroom door, and they ran through the house and romped wildly on the beds, rubbing their dirty fur around on the bare mattresses. The few chairs were scratched and chewed.

The smell was overwhelmingâa mix of urine, rotting food, and dog feces. It was hard to have a conversation over the constant barking. Brown smears coated the walls and windows, and the sagging ceiling had completely fallen in places.

Margaret was a large woman of an indeterminate age, with messy hair pulled back in a ponytail. Every day that we were with her, she wore the same permanently stained T-shirt and shorts, which didn't cover the open sores on her arms and legs. She never smiled or even made eye contact with any of us. She didn't seem to care that she lived in conditions worse than in many third-world countries. Margaret is what most people think of when they think “hoarder.”

But there was a time when Margaret wasn't much different from two of my other clients, Brad and Ellen, a middleclass couple raising three small boys in a pretty suburban neighborhood. Ellen was a typical frazzled mom, who got her daily exercise chasing after the kids. Brad was a mellow guy, with dark hair and a little bit of a paunch under his button-down and khakis. The whole family was clean, well dressed, and friendly.

Their house was clutteredâbut not the stereotypical place that one associates with classic hoarders like Margaret. There were piles of clothes, toys, papers, and mail that looked like someone meant to get to them a few weeks ago but had gotten distracted.

The telltale sign of hoarders-in-training: The piles were in every room.

Brad worked with computers, and he had saved a lot of his cast-off electronic equipment in the basement, thinking someone might use it one day. Ellen had been a teacher and had kept many of her old supplies and now-outdated workbooks.

Ellen was having trouble keeping up with laundry, with stacks of dirty and clean clothes on the chairs and in front of the washer. The kitchen cabinets were bulging with boxes and cans of food that the two of them liked to stock up on when they were on sale.

Brad and Ellen just couldn't let things go, and weren't processing the avalanche of stuff that comes with raising three active boys. Left unattended for much longer, the clutter would become full-blown hoarding and overwhelm them and their small house.

According to a study by Johns Hopkins University, there are an estimated 12 million hoarders in the United States. Four percent of the population is somewhere in the range of Brad and Ellen to Margaret.

Hoarding isn't about how much stuff a person has. It's about how we process things. Most people can easily make decisions about what to keep and what to toss or donate, and then they follow through. A hoarder can't. There's something off-kilter in the hoarder's brain that we don't fully understand yet. It starts small, and then it gets out of hand.

Hoarding begins like this: Most people who go to a fast-food restaurant and get a cold soda then throw away that big plastic cup when they're done drinking. Maybe they even recycle it. But a hoarder has issues with that cup. The cup is useful. It's a pretty sturdy cup, not a flimsy little paper thing. Maybe a church feeding program or a homeless shelter could use it. Carelessly tossing that cup in the trash would be a waste when there are so many people in this world who can use a good cup. So the hoarder keeps it, intending to get it to the church or shelter. It just never gets there.

Or that cupâdecorated with colorful cartoon charactersâis meaningful because the hoarder went to the fast-food place with her toddler daughter as a special treat. The moment was an important emotional memory for the mother, and looking at the cup brings back that joyful experience. Throwing away the critical link to such an important occasion is unthinkable.

Hard-core hoarders go through this internal debate with every single item that crosses their path: plastic bags, junk mail, wine corks, fast-food chopsticks, and soy sauce packets. They are the ultimate recyclers, but for some reason that cycle never gets completed. At some point hoarders lose the stuff-management battle and get overwhelmed. The piles grow, the trash overflows, embarrassment builds, and they stop letting people into their homes. Without help, they have no idea where to even begin to clean up.

Once the possessions start to take over, hoarders tend to get attached to the items no matter what they are. Being surrounded by piles of stuff can be strangely comforting. The stuff is there, day in and day out. It doesn't change, it doesn't leave, it doesn't even move unless the hoarder wants it to. Hoarders feel like they have everything they needâlots of clothing, spare toothbrushes, extra food. They're in the land of plenty where they are in charge and control everything.

SEPARATING HOARDING FROM MESSINESSHoarding isn't a character flaw. It's not laziness or forgetfulness. It's a mental disorder. While scientists and medical professionals are still figuring out exactly what hoarding is and what causes it, most agree that it is a glitch in the brain that manifests itself by making a person want to hang on to things, whatever those particular things may be.

The critical thing is how to determine if someone is just messy or a bona fide hoarder. Everyone builds up a few piles now and again, and many of us have a growing “collection” of something like porcelain Christmas houses or old

Sports Illustrated

magazines. When is that a problem?

Sports Illustrated

magazines. When is that a problem?

Hoarding is an issue when the clutter begins to affect the activities of everyday life: cooking, cleaning, entertaining, and moving freely about the house. In the early stages it can be difficult to tell hoarding from messiness. Someone who shuffles piles of junk mail around the kitchen counters or who is too embarrassed by a messy house to invite people over might just be on the slippery slope to hoardingâor not. If the clutter gets progressively worse instead of better, it's probably hoarding.

Other books

Spice & Wolf I by Hasekura Isuna

Artifact of Evil by Gary Gygax

Private Emotions – Promises (The Private Emotions Trilogy) by Amornette, Elize

What Just Happened? by Art Linson

Sweet as the Devil by Johnson, Susan

Intellectuals and Race by Thomas Sowell

Falling Free: What happens in Vegas... (The Fall Series) by Rossi, Annica

Head Over Heels by Gail Sattler

Three Is Just Enough by Jon Keys

A Scandal to Remember by Elizabeth Essex