The Silk Road: A New History (16 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

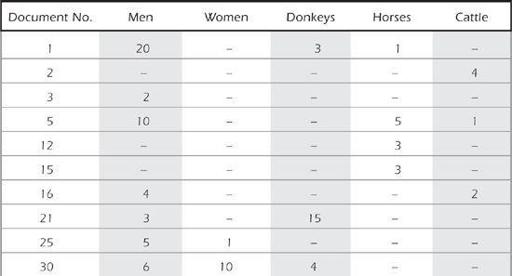

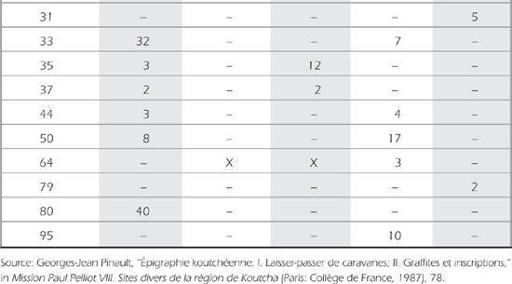

TABLE 2.1 COMPOSITION OF CARAVANS IN KUCHA, 641–644

These documents are important because few sources detail the size of caravans. The dynastic history of the Zhou dynasty (557–81), which was composed around 629, tells of a caravan going to Wuwei, Gansu, that consisted of 240 non-Chinese merchants, with six hundred camels who carried 10,000 bolts of multi-colored silk.

66

This was before the Sui reunified the empire, when travel was difficult; merchants formed large groups, often hiring guards, to ensure their own safety. The Kuchean travel passes indicate a routinization of caravan travel in the seventh century: because the roads were safe, travelers could move in smaller groups.

These different sources—the official Chinese histories, coin finds, and the Kuchean-language documents—portray a thriving local economy in which a money economy in coins coexisted side-by-side with a subsistence economy. In 648 the Tang-dynasty armies conquered Kucha. The Bai-family rulers went from being vassals of the Western Turkish kaghanate to subjects of the Tang dynasty. Kucha was the site of the headquarters that administered the “Four Garrisons of Anxi” (Kucha itself being one of the four). The Tang maintained only intermittent control for most of the following century; the other three garrisons were Khotan, Kashgar, and Yanqi (between 679 and 719 Tokmak replaced Yanqi).

67

Like the Han dynasty before them, the Tang established garrisons in the Western Region, but with one crucial difference: they used the same administrative system for the Western Regions as for the traditional core areas of China. The prefecture of Kucha was structured exactly like a prefecture within central China. Prefectures were divided into counties, which were divided into villages in rural areas and quarters in urban areas.

Our best information about the Chinese occupation comes from a severely damaged group of documents that Pelliot found at the Duldur Aqur monastic site just south of Kucha: 214 scraps of paper, many of them damaged by fire and highly fragmentary, with Chinese on them. The earliest ones date to fifty years after the Tang conquest, the 690s, a time of much political turmoil. At the end of the seventh century, the peoples living in Tibet formed a powerful expansionist empire that challenged Tang control of Central Asia in 670, and the Tang managed to reassert control in Kucha only in 692.

68

Then, after fifty years of stable Chinese rule, a rebellion led by a part-Sogdian, part-Turkish general named An Lushan almost brought down the Tang dynasty, which defeated the rebels only in 763 after hiring mercenary troops.

Although the Tang dynasty was much weakened and Tang armies withdrew from Central Asia, Chinese military colonies, under the rule of the Anxi Protectorate, continued to exist in Kucha. Between 766 and at least 781, a Chinese official named Guo Xin served as the highest official in the Anxi Protectorate, based in Kucha, but had no contact with the Tang court in Chang’an.

69

In 781 Guo Xin reestablished contact with the Tang by sending envoys but continued to govern on his own. The Tibetans conquered the region in 790, although they have left minimal traces in the archeological record, and the Uighurs took over Kucha in the early ninth century and remained in power until the coming of the Mongols in the thirteenth century.

70

The Chinese documents from Duldur Aqur start in the 690s, when the Tang was still powerful, and continue through 792, when the Chinese finally lost control of Kucha.

71

Unlike the Kuchean religious texts and monastic accounts, the Chinese materials cover secular matters too. Written by Chinese soldiers stationed in Kucha, they include letters home as well as three funeral notices praising the deceased for their military prowess. One contrite believer lists various violations of Buddhist proscriptions committed while in military service: drinking alcohol, eating meat, breaking a vegetarian fast, damaging monastic property, and harming sentient beings.

72

These materials document a range of activities: monks reciting sutras in a monastery, women writing letters, the size of agricultural plots, the number of banners used in Daoist religious ceremonies, and an evaluation of an official’s performance.

73

These documents point to a separate Chinese settlement, possibly a garrison staffed by soldiers living with their dependents.

74

These materials, like the Kuchean-language travel passes, document the movement of caravans, which various letter writers used to send their correspondence. One letter writer, apparently en route himself, writes so quickly that he repeats certain phrases, in order to finish his letter in time to give it to a group of colonists returning to Kucha.

75

The main item of trade mentioned in these documents is horses, which the Chinese bought from the nomadic peoples north of Kucha in exchange for one thousand catties (roughly 1,300 pounds, or 600 kg) of steel or roughly 1,000 Chinese feet of cloth. One account gives the amount and type of grain (crushed grain with soy, bran, or barley) given to government officials for the horses in their care.

76

The militia and different expeditionary armies used horses, as did the postal and relay stations.

77

One letter is from a horse merchant who reports the illness of a horse that subsequently recovered. Other sources confirm that Sogdians, either immigrants from Samarkand and its environs or their descendants, played an important role in supplying the Tang army with horses, and the Duldur Aqur scraps contain a few faint traces of Sogdian presence.

78

Like the documents from the garrison at Loulan, these documents point to the existence of trade, but it is a trade carried out by Chinese officials purchasing what they need: mostly horses. Fragmentary and difficult to interpret, they document the existence of government-sponsored trade above all else.

Consistent with this picture of government-sponsored trade is the frequent mention of coins in Duldur Aqur documents. They document a monetized economy in which certain individuals spend considerable amounts in individual transactions. One person without an official rank paid a tax of one thousand coins to be exempted from a labor obligation; another paid 1,500 coins. A list of debtors gives the amount of money paid by the people whose names appear: 4,800 coins, 4,000 (possibly more) coins, 2,500 coins.

79

Archeologists have found eleven Chinese-language contracts at other sites in Kucha. Three of the best-preserved Chinese contracts are for loans of one thousand coins each; the borrower agrees to pay back the loan in installments of two hundred coins.

80

Who minted all these coins, and why? Where some historians of Rome have identified the state as the most likely producer of coins, since it paid soldiers, others point out that if local markets had not existed, soldiers would not have needed coins.

81

The Tang state collected taxes and made payments in three types of currency: coins, measures of grain, and cloth (usually bolts of a fixed length of silk). Their extensive payments to their armies resulted in ample supplies of coins circulating throughout Kucha.

In 755, with the An Lushan rebellion, the Tang dynasty withdrew its forces from Kucha and the flow of coins into the region came to a sudden halt. The authorities at Kucha responded by minting their own inferior copies of Tang coins. Using a coin from the Kaiyuan (713–41) era to make a mold, they replaced the two characters for Kaiyuan with the name of the new eras proclaimed by the Tang emperor (Dali, 766–69; Jianzhong, 780–83). Cruder than the original characters, the new characters include some mistakes. These Kucha-issued coins have other signs that they were not minted by the central government: their central holes are sometimes octagonal instead of rectangular (because the molds were not aligned properly). The metal in these coins was also a redder copper than used in central China, another sign of local manufacture. One thousand coins of this type have been found in Xinjiang, of which eight hundred came from the Kucha region. Only two were found in central China.

82

Clearly these coins circulated primarily in Xinjiang. Even though Kucha was cut off from the Tang, the different local rulers still had to pay their troops, and they needed coins to do so.

Undeniably, the Chinese-language materials from Duldur Aqur are limited. Totaling only 208 documents, many of them consisting of a few characters, they touch on a surprising range of activities. The historian who has translated these documents into French, Éric Trombert, summarizes their content: “One other characteristic of the Chinese materials from Duldur Aqur—collected by Pelliot and Ōtani—is the absence of identifiable commercial documents. No lists of goods destined to be commercialized. No travel documents like the many travel passes for caravans found near the postal station at Yanshuigou. Few contracts, which seem to be mostly transactions among peasants.”

83

Yet for all their variety, they do not mention anything that looks like the conventional portrait of the Silk Road trade—no private merchants carrying vast quantities of goods across long distances. Trombert believes that Kucha was a center of commerce, but that the merchants traveling there stayed within the city or outside the oasis—not at Duldur Aqur, which is why no commercial documents survive.

Yet, like Duldur Aqur, the much-better-documented sites along the Silk Road also lack documents about long-distance trade. The body of materials from Kucha in Agnean, Kuchean, and Chinese, the focus of this chapter, is certainly the most piecemeal and damaged of any site discussed in this book. All the Chinese and Kuchean materials from the Kucha region combined total under ten thousand scraps; of these, only several hundred documents are preserved well enough to be read and understood. There was trade in Kucha, but, as the travel passes show, government officials supervised it closely, and, as the materials from the Chinese garrison at Duldur Aqur reveal, the Chinese army’s demand for horses constituted a major component of that trade. Even in the late 700s, when military conflict was endemic, local rulers continued to mint coins—an indication of how closely tied the trade was to the presence of armies.

The surviving evidence from Kucha, as partial as it is, suggests an alternative to the standard picture of the fabled Silk Road trade: rather than a long-distance trade initiated and staffed by private merchants, these materials indicate that the Chinese military contributed significantly to the Silk Road economy. When Chinese armies were stationed in Central Asia, money—in the form of coins, grain, and cloth—flowed into the region. When the Chinese troops withdrew, small-scale trade resumed, largely maintained by local travelers and peddlers.

CHAPTER 3

Midway Between China and Iran

Turfan

L

ocated on the northern route around the Taklamakan Desert, Turfan bridged the Chinese and Iranian worlds. Even today, Turfan retains some of its cosmopolitan feel. Vendors on every corner sell naan, the leavened flatbread like that eaten in Central Asia and north India. At a conference I attended there in the mid-1990s, one Norwegian professor of Iranian languages cheerfully greeted everyone at breakfast, explaining that it was the first time he had woken up to the sound of braying donkeys since being in Iran before the 1979 revolution. In town, one sees many Uighur and Chinese faces, and the proprietors at the bazaar—even Chinese speakers say

“baza’er”

and not the Chinese word for “market”—proffer rugs, glistening jeweled knives, and always a glass of tea to potential customers.