The Silk Road: A New History (13 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

Usually jataka tales reinterpreted preexisting Indian folk tales to teach Buddhist values. The tale of the monkey king, for example, told of a band of monkeys who stole fruit from a king’s garden. The king’s guards chased the monkeys to a wide river, and their leader made his body into a bridge so that they could cross. Then he fell into the river and died. This traditional folktale, according to the Buddhist explanation, illustrated the willingness of the Buddha, here the monkeys’ leader, to sacrifice himself for others.

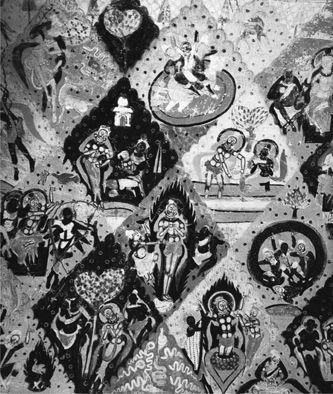

KIZIL CAVE PAINTING

This detail from the barrel roof of a Kizil cave shows the characteristic postage-stamp lozenges local artists used to depict scenes from the Buddha’s earlier lives. Each lozenge portrays a major event from a single jataka tale, affording local storytellers an opportunity to tell the whole story for the entertainment of visitors to the caves.

Another jataka tale, shown in several caves, particularly appealed to merchants. It told of a group of five hundred merchants traveling at night. When it became so dark that they could no longer see, their leader—the Buddha in a previous existence—wrapped his arms in white felt, which he drenched with butter, lit like torches, and lifted up to illuminate the merchants’ path. In this tale, too, the Buddha sacrificed for the sake of others. Devotees who listened to monks tell these jataka tales understood nirvana as something that only the Buddha and few other eminent monks could attain, a key teaching of the early Buddhists.

Today the biggest cave at Kizil (no. 47) stands empty. Fifty-five feet (16.8 m) tall, it originally held a large statue of the Buddha, which would have been visible from far away to travelers coming to the site along the Muzart River. This kind of monumental Buddha cave did not originate at Kizil; the Bamiyan caves of Afghanistan contained similar giant statues, which the Kizil cave builders must have known about. Five rows of holes for wooden posts on both sides of this large cave suggest they originally supported platforms for smaller Buddha figures flanking the larger image. Other caves at Kizil held large Buddha images, no longer in place, and a visiting Chinese monk reported that two Buddha figures, each more than 90 Chinese feet (roughly 90 feet, or 28 m) high, stood outside the western gate of the city and were worshipped at a major festival every five years.

7

Even the most casual visitor to the Kizil caves today notices the many gashes in the cave walls where sections were removed. All the world’s major collections of East Asian art contain paintings displaying the still-fresh deep lapis lazuli blues and malachite greens of Kizil art; most were removed before the outbreak of World War I in 1914. The German holdings in Berlin are particularly extensive.

Le Coq pioneered a new technique for removing the fragile paintings, which he proudly described:

The process of cutting away the frescoes is somewhat as follows:

The pictures are painted on a special surface-layer, made out of clay mixed up with camel dung, chopped straw, and vegetable fiber, which is smoothed over and covered with a thin layer of stucco.

To begin with, the picture must be cut round with a very sharp knife—care being taken that the incision goes right through the surface-layer—to the proper size for the packing cases. The cases for transport by carts may be large, somewhat smaller for camels, and smallest for horses.…

Next, a hole must be made with the pickaxe in the wall at the side of the painting to make space to use the fox-tail saw; in the excavated rock-temples, as we have said, this space often has to be made with hammer and chisel in the solid rock, which fortunately is very soft.

8

This step-by-step description has a chilling effect, as one can easily imagine the damage inflicted on the art. Some Europeans thoroughly disapproved of removing the paintings. Le Coq’s colleague Albert Grünwedel felt, instead, that the sites should be sketched and carefully measured so that, if desired, replicas could be made in Europe. His was the minority view at the time.

A year after the arrival of the Third Expedition, the French scholar Paul Pelliot came to Kucha for an eight-month stay in 1907 when he collected many important documents in the local language of Kuchean. He also devoted one month to exploring the routes north through the Tianshan Mountains. Following the Muzart River north out of Kizil, he found two routes that connected the Tarim Basin with the grasslands to the north.

9

These grasslands, spanning the northern half of Xinjiang (Zungharia), modern-day Kazakhstan, and neighboring Uzbekistan, were home to a succession of nomadic peoples, who posed a continuous threat to successive Chinese dynasties over the centuries.

Kucha’s location on the route to the grasslands of Central Asia led to its earliest appearance in official Chinese histories. When, at the end of the second century

BCE

, the emperor Han Wudi sent the general Li Guangli to visit the ruler of the Ferghana kingdom in modern-day Uzbekistan, he traveled via Kucha.

10

Like the rulers of the Loulan kingdom, the rulers of Kucha did their best to maintain good relations with both the Han dynasty and its enemy, the Xiongnu confederation, which controlled the grasslands of modern Mongolia. Between 176 and 101

BCE

, the rulers of Kucha acknowledged the superiority of the Xiongnu by sending their sons to live with them. It was customary for subordinate kingdoms to send their crown princes to live with their most important allies so that they could learn their language and familiarize themselves with their customs.

But when the Xiongnu weakened, the rulers of the Kucha kingdom shifted their allegiance to the Han dynasty in the first century

BCE

.

11

The king of Kucha and his wife traveled to the Han-dynasty capital in Chang’an in 65

BCE

, where they stayed for a year. In 60

BCE

, the Han dynasty appointed a governor general, its official in charge of the Western Regions, to oversee its operations in Central Asia. This was the office that supplied the center with the information about different oasis kingdoms of the northwest, which is recorded in the dynastic histories. The official history of the Han dynasty gives the population of Kucha as 81,317, making it the largest oasis on the northern route.

12

Little evidence of Han rule survives in the region itself. The Chinese headquarters were in modern-day Cedaya (Luntai County, Kucha), where the ruin of a Han-dynasty settlement has been found.

13

In 46

BCE

Kucha fell to the neighboring oasis state of Yarkand.

The constant jockeying for power among the different Central Asian states meant that the Han dynasty was able to keep control of its garrison only intermittently. The Han general Ban Chao was named governor general in 91

CE

, and managed to reestablish Chinese control in Kucha and place members of the Bai family on the throne. But less than twenty years later, in 107, several oasis kingdoms rose up against Chinese rule, and the Chinese again lost control of the garrison. Starting at this point, and continuing in later centuries, the Bai family regained power and ruled Kucha, sometimes in their own right, sometimes after submitting to a neighboring power.

By the fourth century, when Kumarajiva was born, Kucha was an established center for Buddhist studies. Several translators with the family name Bai, most from the royal family of Kucha, participated in the translation effort. In the third century, the earliest dated evidence of Buddhism in Kucha,

14

many were active in the Sarvastivadin school, which subscribed to Hinayana teachings.

15

The residents of Kucha learned about Buddhism from Indian missionaries. The third and fourth centuries marked the peak of Indian influence, as illustrated by the ease with which Kumarajiva and his parents traveled between India and Kucha.

Kucha provided the perfect environment for the future translator to grow up in. The oasis kingdom had extensive ties with Gandhara, because the rivers across the Taklamakan led to the southern oases of Yarkand and Khotan, from where travelers crossed through the mountains to reach Gandhara. Kumarajiva’s father was an Indian prince, the son of a high minister, who left Gandhara so that he could pursue his studies of Buddhism at Kucha. When the king of Kucha pressured him to marry his younger sister, Kumarajiva’s father reluctantly assented to the match. The child of this union, Kumarajiva grew up speaking Gandhari and the indigenous language, Kuchean.

Kumarajiva’s mother was a devout Buddhist who did not want to live a married life. When Kumarajiva was seven years old, she requested permission to join a Buddhist order, but her husband refused. After she went on a hunger strike of six days, her husband gave in, and she entered a nunnery, taking Kumarajiva with her. Kucha was one of the few places outside India where women could take vows; one Buddhist text lists four nunneries at Kucha with between 50 and 170 nuns each.

16

After studying in Kucha, Kumarajiva traveled with his mother to Gandhara to study texts with a Hinayana teacher. Kumarajiva then moved to what is now Kashgar for further study with a Mahayana teacher. He later returned to Kucha, where he converted some monks to Mahayana teachings. Although later Buddhist sources assert a sharp division between Hinayana and Mahayana teachings, the situation was much more fluid during Kumarajiva’s lifetime. When a young man entered the Buddhist order, he took vows from a monk ordained in a given Buddhist lineage. Membership in a lineage, like the Sarvastavadins, did not determine whether one followed Hinayana or Mahayana teachings. One could begin by studying Hinayana texts, as Kumarajiva did, and then study Mahayana texts. Monks who identified with the two schools lived side by side in the same monasteries and apparently saw no problem in doing so.

17

COMMEMORATING KUMARAJIVA

An imposing bronze statue of Kumarajiva greets all visitors to the Kizil caves, evidence of the translator’s fame even today. In fact, we have no idea what Kumarajiva actually looked like. Since no portraits survive, the sculptor based this entirely on his imagination. Courtesy of Takeshi Watanabe.

Yet in practice some differences between Hinayana and Mahayana teachings were obvious. Where Hinayana monks believed that it was acceptable to eat meat as long as an animal had not been killed expressly to feed them, Mahayana monks refused all meat. One later traveler noticed that Kuchean monks ate meat, scallions, and leeks—all banned by Mahayana orders—and concluded that Kucha must be predominantly Hinayana.

18

In 384, when Kumarajiva was around forty years old, his home city of Kucha fell to the armies of a general named Lü Guang. A description of the city at this time survives:

The city wall had three overlapping enclosures and was equal in area to Chang’an. The pagodas and temples inside numbered in the thousands. The palace of the Bai kings was imposing and lovely like the residence of the gods. The non-Chinese of the city lived luxurious and rich lives. Their homes had stores of grape wine verging on a thousand piculs [about 500 gallons, or 2,000 L] that did not spoil even after ten years. The soldiers drowned themselves in the wine of the successive households that stored it.

19

After his forces took the city, Lü Guang sent Kumarajiva to his capital at Liangzhou (now Wuwei, Gansu) as an expression of his piety. Although Kumarajiva had taken a vow of celibacy, he was, the general believed, too great a teacher not to father his own children. Accordingly, the general made him drink too much and then tricked him into sleeping with a young woman. This is the first of three occasions on which according to Kumarajiva’s biographers he violated his vows.