The Silk Road: A New History (17 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

Historically, Turfan had a mixed population. Migrants from China and Sogdiana, the region around Samarkand, formed the largest communities. After the fall of the Han dynasty in 220

CE

the Chinese migrated in large numbers to the northwest. Turfan and Kucha were the two largest settlements on the northern route around the Taklamakan. The Chinese residents of Turfan listened to Iranian music as they, man and woman alike, performed the Sogdian swirl, a wild twirling dance that was all the rage, shown in color plate 14. To the Sogdians, Turfan felt so Chinese that they called it Chinatown.

1

The Sogdians and the Chinese overshadowed the indigenous residents, some of whom originally spoke Kuchean. Turfan’s residents had already started using Chinese characters in 273, the date of the earliest excavated document found so far at the oasis. The sources from Turfan are particularly significant because the inhabitants recycled paper with writing on it to make shoes, belts, hats, and clothing for the dead. The records preserved in this way form a random, unedited sample that offers an unparalleled glimpse of life on the Silk Road during its peak.

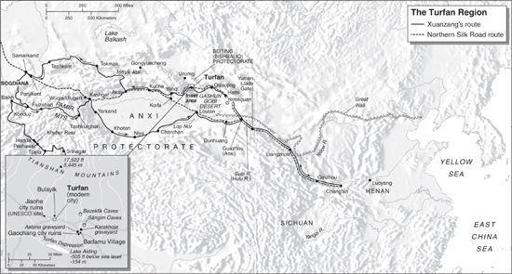

When the southern route fell into disuse after 500, many travelers opted for the northern route that went through Turfan. One such traveler was a Chinese monk named Xuanzang (ca. 596–664) who decided in 629 to go to India to study the original Sanskrit versions of several Buddhist texts whose Chinese versions did not make sense.

2

His timing could not have been worse, since an imperial ban on travel beyond the borders of the new empire was then in effect.

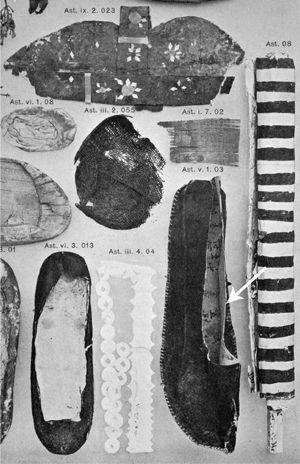

RECYCLED PAPER GOODS FROM THE ASTANA GRAVEYARD

To save space in his archeological reports, Aurel Stein labeled similar items from a single site and photographed them together on the same page. This photo shows some of the paper goods he found at the Astana graveyard in Turfan: a hat decorated with flowers, a rolled-up flag, a string of coins, and, most typically, shoes. Craftsmen cut paper documents into shoe soles and covers, sewed them with thread, and then blackened the exterior. The arrow marks the writing still visible inside one of the shoes. By disassembling such items and reconstructing the original documents, archeologists have learned much about life along the Silk Road.

We know about his trip because Xuanzang dictated a detailed account of his harrowing journey to his disciple Huili (615–ca. 675) in 649 after he returned to China.

3

As Huili relates, Xuanzang was born near Luoyang, Henan, entered a monastery while a teenager, and left the city in 618 when the Sui dynasty collapsed. For eleven years he read Buddhist texts, first in the Tang capital of Chang’an (modern Xi’an, Shaanxi) and then in Sichuan Province. In preparation for his trip, he studied Sanskrit, the Buddhist liturgical language that was also spoken in monasteries.

4

To travel the 350 miles (550 km) between Dunhuang and Turfan, visitors today can choose between an overnight train ride and a one-day car trip. The ease of travel nowadays, however, obscures the genuine perils the journey posed in the past. The first leg of the trip took Xuanzang to Liangzhou, modern Wuwei in Gansu Province, an important city where “merchants and monks from the different countries east of the Pamirs came and went without pause.”

5

Wuwei was the last city inside Tang-dynasty China of any importance; from there one could join caravans going west.

The city’s top-ranking official, the prefect, urged Xuanzang to abandon his plan to leave China. But a local Buddhist teacher helped him to proceed to Guazhou, where the local prefect tore up an imperial order for Xuanzang’s arrest and urged him to depart as soon as possible. (Xuanzang did not pass through Dunhuang, only nearby Guazhou.) At Guazhou, Xuanzang learned of the obstacles on the way to Hami, the first major stopping point beyond the Chinese border: the rapids of the Hulu River, five successive watchtowers to the north that kept a lookout for unauthorized travelers, and, finally, the Mohoyan (Gashun Gobi) Desert. Retracing Xuanzang’s footsteps in 1907, Aurel Stein estimated the distance Xuanzang covered at 218 miles (351 km).

6

He found Huili’s account remarkably accurate, with one exception; Huili omitted two days of walking between the first and fourth watch-towers, probably to speed up the narrative.

Since there was no clearly marked road, Xuanzang hired a guide, Shi Pantuo, to take him to Hami. The guide’s last name, Shi, indicated that his family had originally come from the region of Kesh, or Shahrisabz, outside Samarkand, Uzbekistan, while his given name, Pantuo, was the Chinese transcription of Vandak, a common Sogdian name meaning “servant” of a given deity.

7

Vandak introduced the young monk to an elderly Sogdian who had already made the trip to Hami fifteen times and urged Xuanzang to trade his horses for the monk’s aged horse. Recalling the prediction of a fortune-teller in Chang’an that he would ride on a thin, red, old horse, Xuanzang agreed to the trade.

Sometime after midnight Vandak and Xuanzang set off. They followed the Hulu River north until they reached a shallow ford where the river could be crossed. Vandak cut down some Chinese parasol trees to make a simple bridge so that the two men and their horses could get to the other bank, where they lay down to sleep. In the middle of the night Xuanzang thought he saw Vandak advance toward him carrying a knife—could this have been a nightmare?—but he prayed to the bodhisattva Guanyin for help, and the crisis passed.

The next morning Vandak explained that he had decided to turn back: “I think the road ahead is dangerous and far, with neither water nor grass, and the only water is by the five towers. One must reach these at night so that one can steal water and keep going, but discovery means certain death.” He and Xuanzang agreed to part ways. Xuanzang gave him a horse as a gift and then set off alone through the desert.

Huili describes the terrors of his master’s solo journey vividly. Following a track through the gravel marked only by the horse dung and dried bones of earlier travelers, Xuanzang hallucinated and saw mirages in which hundreds of soldiers in the distance constantly changed their appearance. When he arrived at the first tower, he hid in a ditch until nightfall. Then, as he was drinking his fill and replenishing his water bag at a water tank, several arrows whizzed past, just missing his knee. He stood up and cried, “I am a monk who has come from the capital. Don’t shoot me.” A watchman opened the door to the tower, and the captain invited him inside to spend the night. The captain promised that a relative of his would help Xuanzang at the fourth gate. There, too, arrows showered Xuanzang until he again explained who he was, and the guards allowed him to pass. The guard-tower captain urged him to proceed directly to the Wild Horse Spring (Yemaquan), about 30 miles (50 km) away, the nearest source of water.

Continuing alone and on foot, Xuanzang traveled a long way without finding the spring. At one point, when he stopped to take a drink, his water bag slipped through his fingers, and all his water drained out. Discouraged, he started back but then decided: “It would be better to go west and die than to return to the east and live!” Wandering in the desert for a full five days and four nights, Xuanzang prayed again to the bodhisattva Guanyin before his horse finally led him to a spring in the desert. He recovered from dehydration and proceeded to Hami, where three Chinese monks received him in a local monastery. He had made it out of China.

Occupying less than a chapter, the account of Xuanzang’s trip from Chang’an to Turfan is only one episode in Huili’s hagiography, whose primary purpose was to record the different miracles Xuanzang had performed. Like all hagiographers, Huili exaggerated the perils of the trip in order to document his master’s piety. Still, the modern reader cannot help wondering about some of the details. Would any Chinese official have torn up a writ of arrest in the presence of the person he was supposed to detain? Why would Xuanzang give a horse to a guide who had menaced him at knifepoint and then left him to travel the most difficult leg of the journey alone? How could the unaccompanied Xuanzang have survived his desert journey? Would two separate watchtower captains have allowed a fugitive, even a Buddhist monk, to pass? Could he have lived five days and four nights in the desert with no water? (Admittedly, Hedin survived six days and five nights without water in 1896.)

8

Huili’s account makes it sound as though the one act that violated imperial orders—leaving China in spite of the travel ban—Xuanzang did entirely on his own. Even though Xuanzang must have originally intended to go directly to see the kaghan of the Western Turks, the main rival of the Tang for control of Central Asia, Huili altered his account so that Xuanzang became a loyal Tang subject who left China on his own and decided only after leaving China to visit the kaghan.

9

Whatever the circumstances of his departure were, Xuanzang’s experience differed significantly from that of ordinary travelers on the northern route. On the Guazhou to Turfan leg of the trip he traveled alone, but almost everyone traveled in caravans. When no travel bans were in effect, caravans applied at the border for a travel pass. Guides would have led travelers on difficult-to-find routes through the desert, and, barring the disasters that befell those whose skeletons lay along the path, they would have survived the trip. Xuanzang’s itinerary underscores the important place of Turfan on the Silk Road. Along with Kucha, it was one of the largest cities in the Western Regions.

As Huili tells it, once Xuanzang left the Tang Empire, his fortunes shifted. Qu Wentai, the king of the Gaochang state, which was based in Turfan, the next oasis after Hami on the northern route, sent an envoy to greet him. Proceeding in the dark, the monk and his guide arrived at the palace at midnight, and the king and his retinue, carrying torches, came out to greet him. The king kept Xuanzang up all night talking, and the next morning, while the monk was still asleep, the royal couple waited outside his door so that they could show their devotion by being the first to greet him in the morning. Xuanzang then moved to a monastery for ten days before deciding to resume his journey.

THE RUINS OF ANCIENT GAOCHANG CITY

The dirt walls of Gaochang City near Turfan are among the few genuine above-ground ruins in all of China. Visitors can see where the residents dug into the ground to make dwellings that would remain cool in the summer and piled earth into high walls. Here two dirt towers stand above the other buildings of Gaochang; it is quite likely that Xuanzang preached from one of them after he ended his hunger strike in 629. Author photo.

The king tried to convince him to stay:

From the time I heard the name of the Master of the Law my body and soul have been filled with joy, my hands and feet have danced.