The Silk Road: A New History (38 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

Another group of documents, in Uighur, complements this picture of the peddler trade in the Turco-Sogdian documents. Uighur was the language of the Uighur kaghanates. Few documents in cave 17 are in Uighur—some forty or so.

97

These include religious texts, lists of merchandise, letters, and legal decisions, which mention various locally made goods: cloth (including silk, wool, and cotton), slaves, sheep, dye, camels, lacquer cups, combs, casseroles, steel small knives, pickaxes, handkerchiefs, embroidery, whey, and dried fruits. A few goods, such as silver bowls or silver quivers, may have been of foreign manufacture, yet only musk and pearls are definitely foreign (one letter mentions 117 pearls, the most valuable single item).

98

The authors of these materials describe a world bounded to the east by Suzhou, modern Jiuquan in Gansu Province; to the north by Hami, Xinjiang, and Ötükän on the upper reaches of the Orkhon River; to the west by Miran, near the Tibetan border; and to the southwest by Khotan. The Uighur materials portray a commercial world exactly like that of the Turco-Sogdian materials: local peddlers traveling within a circumscribed area and trading one locally manufactured good for another.

Other scholars have seen these Turco-Sogdian and Uighur documents as evidence of a thriving Silk Road trade.

99

The mere mention of trade confirms their expectations. Although the documents refer only to small-scale transactions involving largely local goods, those predisposed to see a large-scale Silk Road trade see this as sufficient evidence. But all the documents this book has examined—with the exception of the government documents listing massive payments to troops stationed in the northwest—point to a small-scale, local trade, rather than a thriving long-distance trade.

When Aurel Stein first arrived in Dunhuang on March 23, 1907, he encountered a merchant named Sher Ali Khan from Kabul, Afghanistan. His caravan of forty camels traveled from Afghanistan to Khotan and then on to central Gansu; on his way home, he took the Southern Silk Road route as well. His business model was simple. He sold British textiles purchased in Kashmir and Yarkand to the Chinese and bought Chinese silk and tea to sell on his return to Kabul. Sher Ali Khan offered to carry Stein’s mail to Kashgar, and Stein, always glad of a chance to correspond with his friends, immediately began drafting letters and finished writing only at 3 in the morning. Stein then set off to explore the watch-towers of Dunhuang, where he found the Sogdian Ancient Letters. To Stein’s dismay, one evening, as he returned to his camp, he glimpsed Sher Ali Khan’s caravan, which had covered “in eleven days less than eighty miles.” It turned out that the caravan had hired an inexperienced guide who had lost his way in the desert. The disappearance of two valuable ponies delayed the caravan further still. Stein said goodbye to Sher Ali Khan a second time, and, to his surprise, the letters actually arrived in England. His friends received them in the end of September, about six months after he had written them.

100

In the early twentieth century Sher Ali Khan’s caravan carried mostly local merchandise—with the exception of the English woven goods that were newly available in Kashmir and Yarkand. His particular caravan covered a lot of ground, but most of the traders whom Stein and Hedin encountered moved along shorter routes. The documents in cave 17 suggest that the caravans traveling one thousand years earlier were basically the same.

In the Dunhuang economy of the ninth and tenth centuries, locally produced goods circulated in small quantities. Traffic to distant places was limited, commodities of foreign origin rare. The trade had little impact on local residents, who continued to live in a subsistence economy. State-sponsored delegations played a key role in the movement of goods; envoys, including monks, are the one group that was certainly moving from one place to another. This picture of the Silk Road trade matches that given by the excavated materials from the other sites. Rather than trying to explain why the Dunhuang documents do not mention long-distance trade with Rome and other distant points, we should appreciate just how accurate their detailed picture of the Silk Road trade is.

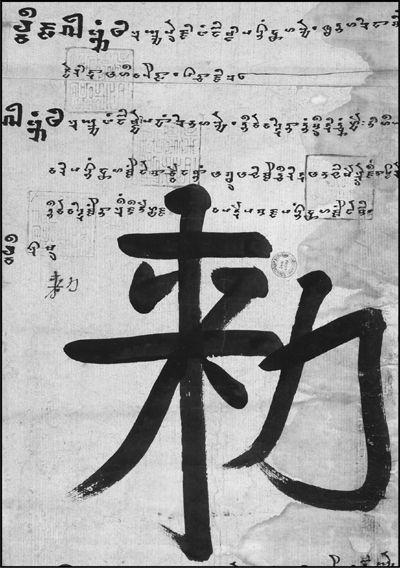

A ROYAL ORDER IN KHOTANESE

In 970 the king of Khotan sent this royal edict to the ruler of Dunhuang, who was his uncle. The use of the Chinese character

chi,

or “edict,” shows how great the influence of Chinese culture was on the royal family. Preserved in the Dunhuang library cave, this is one of the few surviving tenth-century Khotanese documents that was written in the town of Khotan itself and not outside it. Courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

CHAPTER 7

Entryway into Xinjiang for Buddhism and Islam

Khotan

K

hotan, like nearby Kashgar, is famous for its Sunday market, where tourists can buy locally made crafts, naan bread, and grilled mutton on skewers. As visitors watch farmers fiercely bargaining over the price of a donkey, it’s easy to imagine that Khotan has always been this way—but this is an illusion. The predominantly non-Chinese crowd prompts a similar reaction: surely these are the direct descendants of the earliest Silk Road settlers. In fact, though, a major historic break divides today’s Khotan from its Silk Road past. The Islamic conquest of the Buddhist kingdom in 1006 brought a dramatic realignment to the region. Eventually Khotan’s inhabitants converted to Islam, as did those of the surrounding oasis towns, making Islam the principal religion in the region today.

1

They also gradually gave up speaking Khotanese, the language shown on the facing page, for Uighur, the language one hears most often in the city today.

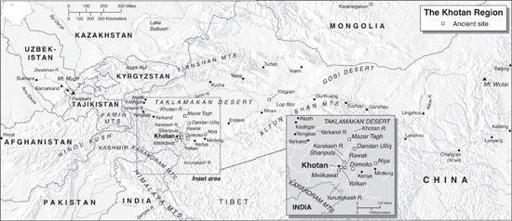

Almost all the materials about pre-Islamic Khotan come from outside the city. Because the oasis sits at the confluence of two major rivers, the environment is relatively well-watered. Extensive irrigation and occasional floods have created a damp environment in which paper and wood cannot survive. Documents about and artifacts from Khotan were preserved in neighboring—and far dryer—desert regions. There are nine major sites: Shanpula, Niya, Rawak, Endere, Melikawat, Yotkan, Dandan Uiliq, Domoko, and, finally, Dunhuang. The earliest finds, dating to the third century

BCE

, are from Shanpula, while the latest, from just before the Islamic conquest, come from the library cave at Dunhuang. Some of these sites are located within the city itself; Dunhuang, in contrast, lies 800 miles (1,325 km) to the east. The materials excavated from these multiple sites make it possible to reconstruct Khotan’s remarkable history.

Khotan was the largest settlement in southwestern Xinjiang and thus the ideal portal for religions entering the Western Regions from neighboring lands. The first Buddhists came from India sometime around 200

CE

, and for eight hundred years, as Buddhism moved east and became the most important religion in central China, Khotan served as a major center for the study and translation of Buddhist texts.

In 644, when the Chinese monk-pilgrim Xuanzang passed through Khotan, the inhabitants related this legend of the kingdom’s founding: after a son of the great Buddhist ruler Ashoka (reigned 268–32

BCE

) was banished from the Mau-ryan Kingdom in India, he crossed the Pamirs into Khotan and became a shepherd, leading his flocks through the barren desert in search of grass. Childless, he stopped to pray at a temple to the Buddhist guardian of the north. A male child then appeared at the deity’s forehead, while the earth in front of the temple produced a liquid “with a strange taste, sweet and fragrant as breast milk” for the infant.

2

Later versions of this myth have different protagonists—sometimes the prince’s ministers—who come to Khotan, and some describe a dirt breast emerging from the earth, but they agree that migrants from India founded the settlement.

These early versions of the kingdom’s founding do not mesh with the archeological record, which indicates that the site’s earliest residents were nomads from the Eurasian steppe, not migrants from India. The Shanpula (Sampul in Uighur) cemetery, lying 20 miles (30 km) east of Khotan, contains materials dating from the third century

BCE

, the time of the kingdom’s purported founding, to the fourth century

CE.

3

This ancient burial site is worth a visit. Abandoned skulls, wooden tools, and bright red scraps of wool, some two thousand years old, poke out above the ground’s surface. Ancient graves lie next to a modern Muslim burial ground, whose caretakers have joined forces with archeological authorities to protect the much-disturbed site from further plundering.

In the early twentieth century, scavengers sold Aurel Stein some scraps of paper and small wooden items from Shanpula, but Stein never visited the site himself.

4

No one excavated the site systematically until the early 1980s, when heavy rains exposed many burials. Between 1983 and 1995, local archeologists excavated sixty-nine human graves and two pits for horses in an area of 2 square miles (6 sq km). Like many steppe peoples, the inhabitants of Shanpula gave their horses elaborate burials, interring one with a beautifully woven saddle blanket.

The Shanpula graveyard also contained mass graves with up to two hundred people placed in a single pit. The women were buried wearing voluminous woolen skirts, whose many stains and multiple signs of mending indicate previous use by the living. The funerary skirts bear decorative bands of woven tapestry 6.3 inches (16 cm) tall, which were made separately on a small loom; for every color change, the weaver cut off the warp threads and replaced them with a new color.

5

The Shanpula site produced vivid evidence of exchanges with peoples living to the west, none more telling than the leg of a man’s trousers cut from a piece of tapestry, shown in color plate 13 and on the jacket of this book. (All the other trousers found at the site were undecorated.) A centaur occupies the top panel, while a soldier with Western-looking facial features stands below. Although Rome, where images of centaurs were common, is a possible source, certain motifs—particularly the animal heads on the soldier’s dagger—indicate that the kingdom of Parthia in northern Iran, nearer to Khotan, was the more likely place of origin.

6

Goods from other societies were buried in the Shanpula graves as well. Four mirrors were of Chinese manufacture and date to when the Chinese first stationed garrisons in Khotan at the end of the first century

CE

. The dynastic history of the Han records the oasis’s population as 19,300 people living in 3,300 households.

7

The mirrors, like those found at Niya, were most likely gifts presented by Chinese envoys to local rulers.

By the year 300

CE

, the mass burials die out, an important indicator of cultural change. The later graves at Shanpula, which contain single individuals buried in rectangular pits, closely resemble those at Niya and Yingpan, suggesting that a related population had moved to Khotan by the third and fourth centuries

CE

and displaced the earlier residents.

This was the time of the Kharoshthi documents from Niya, which frequently mention Khotan, some 150 miles (250 km) to the west of Niya. The Niya officials welcomed refugees from Khotan even as they bemoaned the cavalry attacks and raids by the Khotanese.

Distinctive Sino-Kharoshthi coins, with Chinese characters on one face and Kharoshthi script on the other, testify to the extensive contacts the people of Khotan had with their neighbors. The Khotanese kings created their own hybrid coinage that combined elements of Kushan and Chinese coinage. Numismatic scholars have been unable to match the names of the kings on these coins with the kings mentioned in Chinese sources, making it difficult to date the coins absolutely, but they were probably minted sometime around the third century

CE.

8