The Silk Road: A New History (42 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

The new letter opens with eight lines of greetings by the writer “from far away” to the family of his “lord master Nisi Chilag,” the recipient of the letter, who was most likely a Jew living in Dandan Uiliq. The new letter then details a dispute about sheep that the writer had with a “landlord”: although he gave presents including musk and candy (the meanings of the other commodities he used as gifts are so far unknown), he has not yet received the sheep due to him. Interestingly, he relates a conversation in which the landlord mistook him for a “Sogdian,” an understandable error given how many of the merchants along the Silk Road were Sogdian and how few were Jewish.

Jewish merchants have left only a few traces on the Silk Road. Recall that one of the latest inscriptions on the Karakorum Highway was in Hebrew. An Arabic account of a late ninth-century massacre mentioned Jewish merchants living in the southern city of Guangzhou (Canton) alongside Muslims, Christians, and Zoroastrians. And cave 17 contained a folded sheet of paper with an eighteen-line prayer as well as a selection from the Psalms in Hebrew (shown in color plate 12).

In addition to the single Hebrew prayer sheet and tens of thousands of Chinese and Tibetan-language documents, the library cave at Dunhuang contained about two thousand Khotanese-language documents, many of them fragments.

53

Like many peoples living in small countries surrounded by powerful neighbors, the Khotanese were adept at learning languages. One Khotanese scribe was so skilled that he copied Tibetan texts; we know that he was Khotanese only because he numbered the pages using Khotanese numerals.

54

How did the Khotanese pick up languages so quickly even though they had no dictionaries?

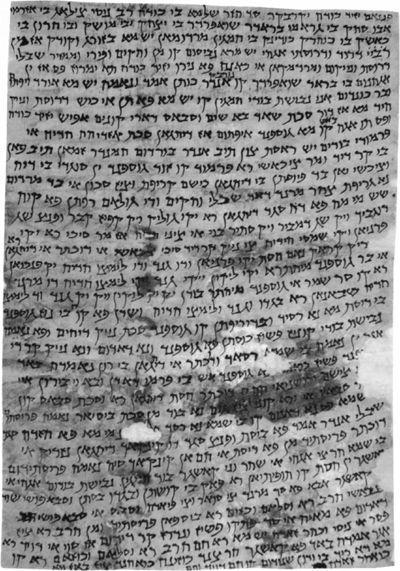

A NEWLY DISCOVERED JUDEO-PERSIAN LETTER

In the early ninth century, the author of this letter, most likely a Persian-speaking Jew, used the Hebrew alphabet to write in New Persian to another Jew living in Dandan Uiliq. The author describes a dispute he is having with his landlord, who has not paid the sheep he owes him. Courtesy of National Library of China.

Several sheets from phrasebooks in Khotanese and Chinese were preserved in the Dunhuang library cave.

55

Dispensing with Chinese characters, these learning aids simply record the sound of the Chinese sentence using Brahmi script and then give the meaning in Khotanese. The extremely skilled philologists who have worked on these texts have reverse-engineered the Khotanese version of tenth-century Chinese pronunciation to reconstruct the original Chinese sentences. Like any good language textbook, the Chinese-Khotanese bilingual list repeats key sentence patterns, all very short, so that the student can practice:

Bring me vegetables!

Bring me cucumbers!

Bring me a gourd!

The phrasebook also includes sentences one can use at a market when buying and selling. Given the many contacts between Khotan and Dunhuang in the tenth century, it seems likely that Khotanese from different walks of life—envoys, monks, merchants—could have benefited from basic instruction in Chinese.

In contrast, the Sanskrit-Khotanese bilingual texts aim at a narrower audience.

56

Sanskrit was easy for Khotanese speakers to learn; because it was written in the same Brahmi script, language-learners could simply copy Sanskrit sentences and commit them to memory. The Khotanese-Sanskrit phrasebook, 194 lines total, begins with a simple conversation:

How are you?

Good, thank you!

And how are you?

Where do you come from?

I come from Khotan.

The dialogues mention other places, too: India, China, Tibet, and Ganzhou (the seat of the Uighur Kaghanate in what is now Zhangye, Gansu). The phrase-book teaches how to buy a horse and obtain fodder, how to ask for needle and thread, and how to request that clothes be washed. Some of the dialogues hint at conflict:

Don’t be angry with me.

I shall not pull out your hair.

When you speak unpleasantness

then I shall become angry.

And some even mention sex:

He loves many women.

He makes love.

Some of the dialogues make it possible to identify the intended users:

Do you have any books?

I do.

[Which books?]

Sutras, Abhidharma, Vinaya, Vajrayana.

Which of them do you have?

Which of them do you like?

I like to read Vajrayana.

Only a monk or an advanced student of Buddhism could use such sentences. “Sutras” was a general term for all Buddhist texts, “Abhidharma” referred to the doctrinal texts, “Vinaya” to Buddhist regulations, and “Vajrayana” to Tantric texts. Sanskrit was spoken in monasteries all the way from China to India, as well as Khotan. One conversation reveals more about the target audience:

I am going to China.

What business do you have in China?

I am going to see the bodhisattva Manjushri.

The intended users were monks traveling on the pilgrimage route that became popular in the eighth century. Starting in Tibet or Khotan, they traveled east, stopping at Dunhuang, with their final destination the devotional center for Manjushri at Mount Wutai in Shanxi (about four hours northwest of Beijing by car).

A gap in surviving documents means that we know very little of Khotan’s history between 802, when the Dandan Uiliq documents end, and 901, when documents from the library cave record that an official in Dunhuang provided Khotanese envoys with one bundle and eight additional sheets of fine paper.

57

In the tenth century, the Khotanese kings were part of the same international order as the Cao-family rulers of Dunhuang: they sent emissaries to and received emissaries from each other, as well as the Ganzhou and Turfan Uighur Kaghanates and the different dynasties of central China. To travel to central China, Khotanese envoys went first to Dunhuang and then Ganzhou before proceeding to Lingzhou (modern Wuling County, Ningxia), an important stopping point for delegations on their way to the capital. Travel to central China was so uncertain that the Khotanese and the two Uighur Kaghanates frequently sent envoys bearing tribute only as far as Dunhuang, which they sometimes referred to as “China.”

58

The Cao family of Dunhuang and the royal family of Khotan had close ties. The Khotanese king Visa Sambhava, who ruled Khotan from 912 to 966, also used the Chinese name Li Shengtian.

59

Sometime before 936 he married the daughter of Cao Yijin. The Khotanese royal family maintained a residence in Dunhuang where Visa Sambhava’s wife often stayed and where the heir to the Khotanese throne lived.

60

The crown prince’s residence functioned as a representative office for the Khotanese, and it is very possible that the Khotanese-language documents found in cave 17 were an archive donated by the crown prince’s residence to the Three Realms Monastery.

61

In 938 Visa Sambhava sent envoys from Khotan to Kaifeng, Henan, the capital of the Later Jin. This is one of five instances during his reign when the Khotanese sent delegations to China, which was unified in 960 by the Song dynasty.

62

The Chinese-language records of these exchanges are typically brief: for example, “On the fourth day of the twelfth month [of the second year of the Jianlong reign, or 961] the king of Khotan Li Shengtian sent an emissary to present one jade tablet and one box” to the founder of the Song dynasty.

63

The Chinese would normally record the date, the name of the country sending gifts, the item presented, and sometimes the name of the lead emissary, but little else.

In contrast, a group of some fifteen Khotanese-language documents preserved in cave 17 offer a wealth of detail about one mission, which consisted of seven princes and their entourage who left Khotan, probably in the mid-tenth century near the end of Visa Sambhava’s reign.

64

These documents reveal much about the nature of trade on the Silk Road, particularly in the difficult conditions of the tenth century.

The princes and their entourage set off with some 800 pounds (360 kg) of jade.

65

In addition, they carried some leather goods, most likely saddles, harnesses, or other horse tack. Horses and jade were the most common tribute items from Khotan, and other recorded gifts included camels, falcons, yak tails, textiles, furs, medicines, minerals, herbs, some types of fragrances, amber, and coral.

66

As was fitting in the subsistence economy of the time, rulers also presented slaves to one another.

67

THE KHOTANESE KING AND QUEEN AS DONORS IN A DUNHUANG CAVE

This painting from cave 98 at Dunhuang shows the Khotanese king Visa Sambhava (reigned 912–66) and his wife, who was the daughter of the Dunhuang ruler Cao Yijin. Ties between the two families were close, and the Khotanese royal family frequently contributed funds for the construction of caves at Dunhuang. Drawing by Amelia Sargent.

Rulers liked these gifts and said so. At one point when the Khotanese and the Uighur Kaghanate of Ganzhou had failed to exchange gifts for ten years, the kaghan wrote to the Khotanese king. (The letter survives only in its Khotanese translation; he probably wrote in either Chinese or Tibetan, the two diplomatic languages of the northwest in the tenth century.) The Uighur kaghan longed for “the many various wonderful things” that the Khotanese delegations had previously brought to him.

68

Most of all, he probably missed the intelligence, particularly about the military strength of rival powers, that only envoys could provide.

69

Travel from one kingdom to another seemed slow, even to people at the time. As one envoy traveling with the princes from Khotan complained, “I shall go as far as Dunhuang making a difficult journey in forty-five days on foot, which with power to fly in the air I had done in one day.”

70

Those who proceeded on horseback took eighteen days to cover 950 miles (1,523 km) by road.

71

No wonder they envied birds the power of flight.

The princes never made it to the Chinese capital; the ruler of Dunhuang felt that travel was too dangerous to go to Ganzhou, where three armies were battling each other in a succession dispute after the Uighur kaghan had died. The Dunhuang ruler insisted that they stay in Dunhuang. The trip ended in total failure, the princes bitterly complained in letters home. Forced to spend the different gifts they carried, the princes ended up utterly destitute, as they wrote:

All the animals our men had are lost. Our clothes are lost.… There is no one with whom we can get out and go to (?) Ganzhou. How can we then come to Shuofang [where the envoys visiting the Chinese capital were first received], since we have neither gift nor letter for the Chinese king? … Many men have died. We have no food. How were then an order to come? How can we have to enter a fire from which we can not bring ourselves back?

72