The Spanish dancer : being a translation from the original French by Henry L. Williams of Don Caesar de Bazan

Authors: 1842- Henry Llewellyn Williams,1811-1899 Adolphe d' Ennery,1806-1865. Don César de Bazan M. (Phillippe) Dumanoir,1802-1885. Ruy Blas Victor Hugo

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

FOREWORD

Some Remarks About Novels That Become Motion Pictures

By Glendon AUvine

The story-teller nowadays does not necessarily write %vith one eye on the screen, but, on the other hand, he cannot shut out from his mind's eye all images of his characters as the camera might reveal them. A very few creative authors still refuse to recognize the films as a new medium of expression.

Some authors to-day are actually writing in front of the camera—devising their plots and characterizations right in the moving picture studio. Most of them, however, are doing their creative writing with only slight concessions to the technical demands of motion pictures.

Homer Croy insists that he wrote "West of the Water ^ower" with no thought whatever that it might make good screen material. When Jesse L. Lasky tried to buy the picture rights of the novel of small town life the author insisted there was no picture in his story—a judgment he revised some months later when he saw the picture in the making at the Paramount studio on Long Island.

"The Covered Wagon" came from the pen of the late Emerson Hough without any thought, on the author's

U Foreword

part, of its picture possibilities. Mr. Hough had had one unfortunate experience with a lesser producer who filmed one of his earlier stories. And as a result he was "off" all picture producers. Yet James Cruze took this novel of the winning of the West and gave it an epic sweep which will make this story live forever, giving the world a better understanding of the hardy pioneers who pushed over the Oregon trail to establish a new; empire of the Pacific Coast. Mr. Hough lived to see his story hailed as one of the great pictures of a decade, and died with a kindlier feeling toward film folk. This one picture revived the interest in all of Mr, Hough's writings and caused "The Covered Wagon" to leap again into the six best seller class of novels.

In his experience with the films Mr. Hough reached the depths of despair and the heights of triumph. Few other authors have run such a gamut from failure to success in the screening of their stories. Some authors have only kind words for the movies; others are loud in their denunciation. Their readers likewise go to extremes in their attitude toward film versions of books. Readers of popular fiction sometimes complain that their entertaining novels have been ruined by the people who make motion pictures. No sooner do I finish reading a novel that gives me a definite idea of intensely human characters I have visualized from the author's words than, along comes a movie director and mangles the pictures I have built up in my own mind. He seems to have no respect whatever for the image my mind has devised and the chances are that his ideas do not coincide with the mental images worked out by any of the many thousands who have read the novel.

And yet how do I know that I am completely right PI 'perhaps he does have a right to his own ideas even as 11

have a right to mine and there may possibly be good and sufficient reasons why a story comes through the picture mill in a form so different from the story I got from the printed page.

My contempt for the movies was second to none when I emerged from college weighted down by two degrees. [VVhat puerile, childish efforts these movies were! What silly, stupid things the picture people perpetrated!

Yet such was my curiosity about the mysterious ways of the makers of photoplays that I set about to learn, as best I could, how they got that way. A motion picture has so many ingredients that the process of devising film entertainment is most complex. It may not be inappropriate to discuss here some of the problems in-yolved. Perhaps some reader whose feelings have been outraged may at least understand some of the mental processes that went into the translation of a novel into a film.

Nobody ever wrote a motion picture in the sense that Booth Tarkington, for instance, writes a novel. Even Mr. Tarkington, perhaps the foremost of living American novelists, feels his own inadequacy in reconstructing his story as a stage play and usually calls in Harry Leon iWilson to help him adapt it to the requirements of the theatre. Mr. Tarkington, in telling his story for the ecreen, likewise requires assistance from specialists in that medium, whose work is often evident on the screen. If there be less of Tarkington at least there is more of a photoplay.

A very few novelists, notably Rex Beach and Rupert Hughes, who have taken the pains to study the complexities of a motion picture production, have achieved considerable success in telling their stories in screen form. Yet either of these creators of fiction feels that a

printed book bearing his own name carries over more of his personality than a motion picture, written, directed, supervised and edited by the author. There are actors and cameramen and bankers and audiences to be considered, and what they do to a story is often the despair of authors with paternal regard for a brainchild.

Even the title is often lost in the shuffle from the printed page to celluloid. Consider, for instance, Bar-rie's "The Admirable Crichton." That story, to the despair of the followers of the whimsical Scot, emerged on the screen as "Male and Female." That was many years ago but people still cite it to illustrate the stupidity, not to mention the cupidity, of picture producers. "Male and Female" is admittedly a box-office title, but the Bible is full of box-office titles. And who shall say that the Bible is not as good a source as Barrie from which to lift the quotation "Male and Female created He them." You can quote scripture even to sell a motion picture.

There is just one reason why "The Admirable Crichton'* was a bad title for a film and that is that very few people, even now, are quite sure of how to pronounce Crichton, Let us imagine a young man taking his girl to the movies. On one side of Main Street the electric lights invite him to view "The Admirable Crichton" and on the opposite side the bulbs blaze out the admonition "Don't Tell Everything." Now he doesn't want to admit to the girl, who is perhaps smarter than himself, his hesitation about pronouncing the title of the one picture and so he avoids embarrassment by suggesting they go across the street to see "Don't Tell Everything." Just multiply that one incident by 100,000—^}^ou multiply almost everything by that number in the movies—and you can appreciate that the earnings of "Male and Female" might have been very considerably less if handicapped in America by the name.

which Barrie, in far-off Scotland, tacked on to his excellent narrative.

I am by no means contending that picture titles are always legitimate or in good taste, but in considering successful titles let us remember that the outstanding music success of a decade was "Yes, We Have No Bananas."

Avoiding a discussion as to whether or not that title means anything, at least we are reasonably safe in assuming that to an American audience "Don Caesar de Bazan" means nothing. Don suggests a Spanish person although Caesar, I believe, was a Roman; and Bazan sounds like a trade name some advertising man might devise for a depilatory. In my estimation, the Famous players-Lasky Corporation displayed excellent judgment in assigning to this story, for American consumption, the simple yet dignified title, "The Spanish Dancer."

That title, I learned, was chosen from many suggested in New York while the film was in production in California. And throughout the months the studio people were laboriously grinding out the 387 scenes that blend into the nine reels of this celluloid entertainment, the advertising and publicity men were attempting to establish in the public mind that title, "The Spanish Dancer." On seeing "The Spanish Dancer" on the screen it is interesting to speculate how many minds have exerted their influence on the story that Victor Hugo imagined in France almost a hundred years ago.

It happened that an actor, Lemaitre by name, had set his heart upon playing the part of Don Caesar de Bazan, a minor character in Hugo's great dramatic poem "Ruy Bias." Victor Hugo had agreed to expand the role of Don Cssar so as to make it the starring part in a stage play suitable for the talents of M. Lemaitre, but Hugo

had incurred the displeasure of both the monarchists and imperialists and so everything he had written or intended to write was banned.

Enter Adolphe D'Ennery and P. S. P. Dumanoir, who adapted the story to the needs of the Parisian stage. Both were dramatists of repute and D'Ennery's fame subsequently reached America as the author of that venerable opus known wherever stock is played, "The Two Orphans."

Enter now two other dramatic craftsmen, June Mathis and Beulah Marie Dix, who adapted the story to the screen and the needs of Pola Negri. For as Victor Hugo wrote the stage play to fit Lemaitre, who played Don Cassar, so June Mathis and Beulah Marie Dix wrote their screen story to put the emphasis on Pola Negri, who is the central figure ir the Paramount picture.

Miss Mathis will be remembered as the author of the continuity of "Blood and Sand," which brought Rodolph Valentino to the peak of his popularity. In their collaboration on "The Spanish Dancer" they have developed a script which retells Victor Hugo's story in the most vivid fashion possible.

Their script so pleased Jesse L. Lasky, on whom rests the responsibility for the selection and production of Paramount pictures, that he assigned it to Herbert Brenon, who had previously directed many film successes. Mr. Brenon, realizing that neither he nor any living person had any first-hand information about the Spain of three centuries ago, began doing research work in the libraries of Southern California and Northern Mexico, but since he could not find there all the authentic historical data needed for the telling of his screen story, he crossed the continent to the Metropolitan Museum of Art where a week's work netted him excellent results. Finding that '

Foreword !vi|

other data were available at the Smithsonian Institute at Washington, he went to the capital for further research work. Photographs were obtained from old prints which served as the basis for the elaborate backgrounds, native customs were studied and blended into the plans for the picture, with the result that when Director Brenon actually began the shooting of his first scene in the picture he was thoroughly steeped in the atmosphere of Spain of the seventeenth century.

To play the part of Don Caesar de Bazan, Mr. Brenon selected a popular actor of Spanish parentage, Antonio •Moreno. This was an almost inevitable selection since Mr. Moreno has many of the ingratiating personal qualities that Victor Hugo attributed to Don Csesar. For the role of that old reprobate, King Philip IV, the director chose Wallace Beery, a competent actor whose villainy on the screen is well known to theater-goers. Kathlyti Williams was assigned the part of Queen Isabel. Gareth Hughes, always good in juvenile parts, was chosen for Lazarillo. Adolphe Menjou, a 100% villain, was selected to create Don Salluste. For the part of the Marquis de Rotundo Mr. Brenon selected Edward Kipling; for the Cardinal's Ambassador, Charles A. Stevenson; for Diego, Robert Brower; for Dib he chose Robert Agnew. The part of Don Balthazzar went to a girl. Dawn O'Day.

Meanwhile designers and architects had adapted from the many Spanish prints dug out of the museums and libraries a whole village which was built in the mountains of Southern California. Nowadays carpenters and plasterers and masons get big wages, and the labor costs in building a village are great, even though the village be an uninhabitable one for motion picture purposes. A studio statistician has figured out that these reproduction$

yiii Foreword

of old Spanish castles actually cost more than did the original castles in Spain from which the sets were modeled. Labor back in seventeenth century Spain was yery cheap. Then you could build a castle in Spain almost as cheaply as you can dream about one now.

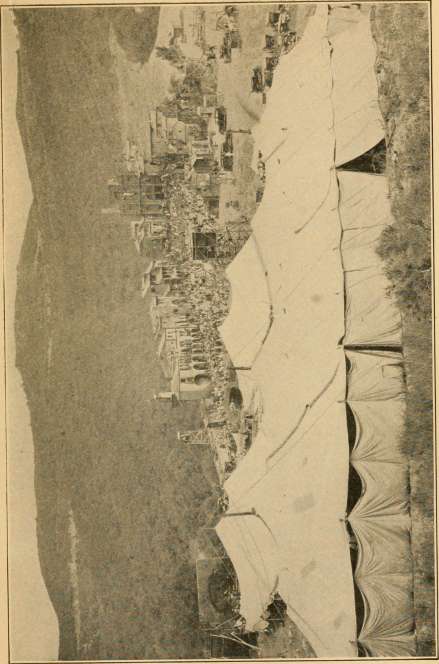

An interesting photograph is included in this book which shows, better than any words can describe, the size and beauty of the great old Spanish buildings grouped about the Catholic church. The hundreds of extra people who appear in this big scene are but specks qn the picture compared with the huge sets built only to be photographed. In the foreground are seen the tents in which the actors lived while on location far from Los Angeles.

Out on this location most of the scenes for the picture were filmed, for it is essentially an outdoors story. But the elaborate garden fete in which four hundred ballet dancers appear was rehearsed and photographed in the famous Busch gardens in Pasadena. The colorful gypsy encampment was established on the Lasky ranch near Hollywood.

When most of the outdoor scenes had been photographed Director Brenon retired to the huge stages of the Lasky studios in Hollywood where the interior scenes of the picture were photographed. Finally, after many months of activity, the actual camera work had been completed. There remained then the complicated and tremendously important work of cutting, titling and assembling the film for one finished print. Out of about 75,000 feet of film which had been exposed and developed it was possible to use only about 9,000 feet, or nine reels.

Each of the 387 scenes in the photoplay, it must be understood, were photographed several times and some-