The Spanish dancer : being a translation from the original French by Henry L. Williams of Don Caesar de Bazan (13 page)

Authors: 1842- Henry Llewellyn Williams,1811-1899 Adolphe d' Ennery,1806-1865. Don César de Bazan M. (Phillippe) Dumanoir,1802-1885. Ruy Blas Victor Hugo

"The Germans," said the shining host, "have a morality; that all good things go in threes. I must say that here we have three good things, indeed," taking his place at the head of the board, "good welcome!"

"All hail Don Caesar de Bazanl"

"Good entertainment!"

A murmur of approval, as from bees at the edge of honey cups.

"And good-sped to the departing host!"

There was a protest in a deep voice at this untimely reminder.

"They all three make good company, the best company! Comrades, for I was an ensign in the Royal Guards, fall to!"

There was a great scuffling as the men dropped into their seats and proceeded to demolish the pies and pasties, which were only made to increase their thirst.

"The sole regret I feel—but do not let it be a damper— is my being compelled to limit our regale! I have an appointment of some moment—very few moments, egad!" .

He stood up, the others at ease, all having fully-charged bumpers. ■

"Aha, Oporto, I hail thee, old and early friend—also, my latest one! 'Tis long since we met, and I have been palmed off with pretenders, who claimed kin with thee,

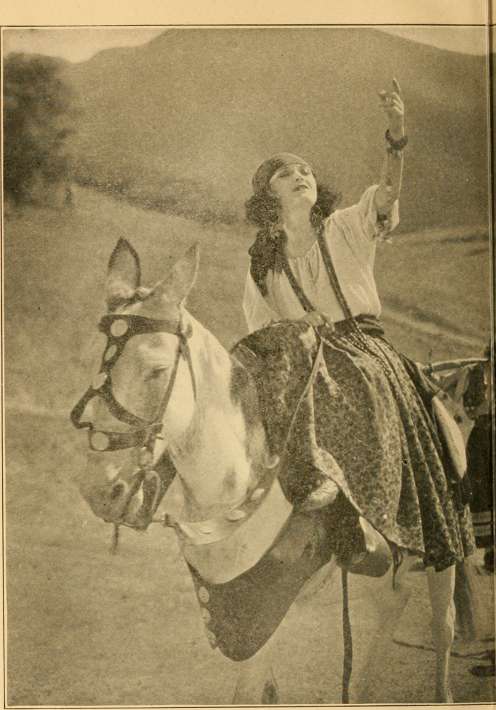

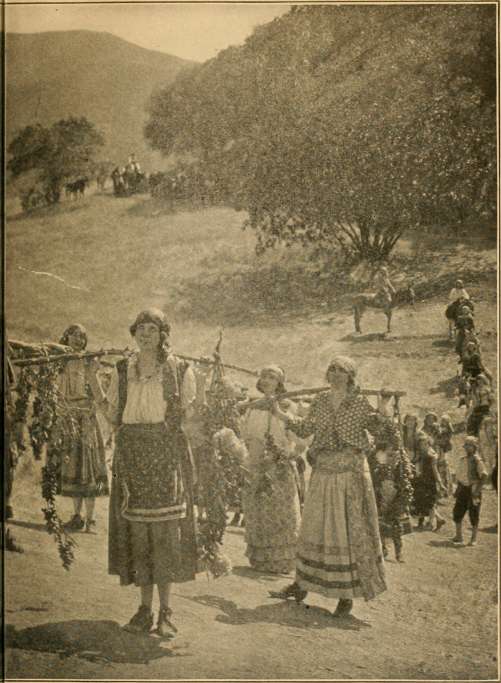

A Paramount Picture.

POLA NEGRI IN HERBERT BRENON'S

PRODUCTION OF " THE SPANISH DANCER."

iwithout foundation of a grape! True descendant of the vine, tempter of Father Noah, who would not have taken to the boats if you had been the chief component of the flood! Offspring of our sister Portugal, me seems, you have a Moorish smack! Fill up again, boys! Now, to one who is not yet entitled to grace my board—to the lady of my house! to the health of the Countess of Bazan and Garofa!"

Rising, the troopers shouted the toast till the rafters of the old Alcazar threatened to be down about their ruddy ears.

"Gentlemen of the Arquebuse," said the host, rising for the last time, "it is proper and of good usage for the traveler starting on a vague journey, the knight pricking forth on his errand, the mariner adventuring to sea, to preach a moral to those who wish him well! Listen to mine, which has the brevity of wit and a novelty which may recommend it!" With an unshaken voice, mellow with the wine, he trolled:

"No doubt there's a lay—(for the rhymer spares none) To the bride of a day, wed in name—still a nun! To no end may you browse, among verse, sweet or sour! There's no line to the Spouse who was wed for an hour!

Oh, soldiers, we're sheep, whose time ne'er's our own,

We let others reap where hast'ly we've sown;

We're roused from the plank; we're marched from the bower.

No rest but where sank the Spouse of an Hour!

Did Methusalem wed? If so, early and once?

Living nine hundred years! Fie! who'd vie with that dunce?

Far happier Jove, when his dread golden shower

Divorced from his love that great Spouse of an Hour !"

He turned amid the somewhat sad applause to the window, which gave a limited view of Madrid's scores of steeples, spires and towers, and said, with false emotion:

"Farewell, my natal city! I have yearned to hang

upon your neck, and you came precious near to hanging me on your gibbet! Farewell, the seventy churches which I have never intruded upon, and the ten thousand taverns, wineshops and popular resorts, where I have run up many a flight of stairs and longer bills! Farewell, blessed bells, which will about the same time ring in my wedding and my funeral! Farewell, squares and g"ardens, where I have laid my drunken pate! Farewell, the palace grand entrance, into which I have been marshaled with the grandees' honors, and the Fuencanal Arch, out of which I have been expelled with my vagrant friends by the beadle of St. Espirito's. Farewell, Hall of Battles in the Escurial, where my ancestors' doughty deeds are depicted, and petty hall of battles in the Next Sovereign ding-house, where my feats are dented in the wall with empty wine pots and knife points which missed my ear! Farewell!"

The clock struck half-past six. The morning was ablaze in the east, and the city glistened in every passage open to the god of day.

There was a flourish of trumpets.

A man clad in black opened the door and shed dullness over the festive chamber by his suit and demeanor.

It was the usher of the prison director. He announced all unpleasant matters, as a stage manager has to apologize for disappointing the audience.

"My lord," said he in a lugubrious croak like a bittern's; "the judge desires a hearing!"

"What, my old acquaintance, the justice of the Insolvent Debtors' Court!" cried the gentleman in the white satin, advancing briskly.

"No, my lord," replied the usher, reproachfully. "The Chief Justiciary!"

"Really? They do the Count of Garofa too mucli honor! Let him come!"

CHAPTER IX.

WEDDED BEHIND PRISON BARS.

There was an impressive show. The judge was accompanied by two juniors, several secretaries, registers, clerks, what not, with a special guard of halberdiers. Don Caesar, in his brightness, seemed a butterfly among bloated black spiders. He bowed to the judge, lowly it was true, but perhaps his bow was even more respectful to the Chief Alguazil, next to the Minister of Police in his estimation.

A tribunal was improvised for the legal dignitary by. placing a chair on a platform, whence the wine butt was drawn, and the judge, flourishing a parchment, intoned in a Jeremiah's voice as follows:

"In the name of the king, Don Carlos, etc.

"His majesty graciously accords to Don Caesar ol Bazan, the Count of Garofa, etc., his royal grace! Thei count will not suffer the death designated to offenders in this degree at the hands of the common executioner, noif yet of the royal headsman, but, by our royal pleasure, will be conducted from the hold of his present prison to the barrack-yard of the Royal Arquebusiers, under their escort, and be shot by a file of the commander's selection."

"It may be to the royal pleasure," murmured the culprit, "but I will be hanged, that is, will be shot! if it is to mine!"

This was not heard by the judge, who darted at him a lingering glance, like one who was losing a prey, and folding up the order, which his clerk took, he solemnly bowed lo the unfortunate man and retired.

lo8 Wedded Behind Prison Bars.

At the door he paused and remarked grumbhngly to his secretary:

"What mountebank's trick is this? He is tricked out like the gypsy dancers, only that the material is genuine. Is he allowed to put all the plunder out of goldsmiths, drapers and bootmakers upon his back?"

"I think, my lord," said the writer, "that, as the condemned leaves all his attire to the deathsmen, he, having been of the guards, in his younger and better days, wants to remunerate them well for shooting him with fatal aim!"

It was a quarter to seven—Don Caesar resumed his stand at the table head, as if they had not been interrupted.

"You will tell me," said he genially, "if a poet's infatuation for his children leads him to surfeit you, but I have just time to enchant you with another couplet of my composition! Little did I think, when I wrote out the rough draft, years ago, in the camp before Tarbes, that this little impromptu should give so much amelioration to the sharpest of pangs!"

They could not do more, for such a host, than fall into "attention," and assume such stolidity as characterizes the military hearing "orders of the day."

"You will pardon me, my lord," said the usher, who had dropped out of the ranks of the sinister cortege, and taken a drink out of a flagon without being asked. "But they are going to smother up this case so that your name may go down to posterity unsmirched."

"You don't say that?" said the host. "They are not going to burn me, that I shall say nothing?"

"But they will burn all the papers!"

"Then they should burn the judges and accessories as well, for that justice is a blab—I can tell that by the mouth on him! Never mind, if my verse is spared, that

Wedded Behind Prison Bars. 109

will be enough to immortalize the Count of Garofa! Not many counts of my house have done so little guiltily as murder—the grammar of his time! To my last verse, gentlemen!"

And as fluently as before he recited:

"So envy the Jack, whose wedlock was curt! If one's snatched off the rack, the less depth to one's hurt. He may mock at the cloud full of storms—let them lour; What of lightning can shroud the blest Spouse of an Hour?"

The recitation was a little marred by an organ in the chapel, tuning up mournfully, and soon the monks were heard practicing a hymneal paeon so dolefully that "the Jubilate" might as well have been "the Misericordium,"

"Hark! she comes! Gentlemen, decorum—here comes my wife!"

Lazarillo appeared at the door and sang out lustily:

"Way for the Countess of Garofa and Bazan!"

Behind a veiled figure, robed in rich white, Don Jose shov/ed himself. He wore a vizard, which concealed his identity from few. Several enigmatical persons, his agents, or the prison governor's servants, brought up the rear. After the sedate judge's cohort, this was tame.

The soldiers had saluted the lady, but embarrassed by the indelicacy of their confronting the spouse of the man they were about to convert into a human sieve, they levanted with celerity. Lazarillo, struck with a sudden thought as he noticed that the wine had got into even their hardened skulls, fleetly followed them, and was eager to make friends with them by proving that he had not forgotten, in becoming a page, the art of loading the firearms.

The marquis whispered to his cousin:

"Bear your promise in mind. Not a word! Not a peep!"

Don Caesar shook his head; the veil was impenetrable.

no Wedded Behind Prison Bars.

"The bride awaits the bridegroom's hand," said the master over this unwonted ceremony.

The count took the hand presented with curiosity; it was soft and yet not wholly that of a court lady, bathed in a g"love of unguent by night and embalmed by day. There was no jewel on it by which a patrician could tell the wearer. It was quite a small hand to belong to that tall figure. It had not a wrinkle; but, then, all the wrinkles might be on the head. He stared in vain, for never had a woman in Christendom been so muffled up before.

He was interrupted in his fruitless scrutiny by Don Jose significantly indicating the time on his watch.

He had ten minutes more.

He gallantly lifted the hand to his lips and imprinted a kiss upon it, while he said:

"]My Dulcina, to you I devote the remainder of my existence!"

A servant took up her train, and the two went out by a door leading into the passage for the chapel.

At every turn and nook there was a warder.

"Verily," observed Don Caesar, "the governor think* I might take French leave. 'But if this, by any chance, is one of those to whom I promised eternal love, he might guess that she would never let me escape between this and the altar."

He could not well beat a retreat, for the prime ministeir followed closely behind them.

"He has no faith in me," muttered the Benedict; "now I hold that it will be fair to thwart him in this detestable fi'cheme."

The marquis' varlet had been left behind; he ceased in a testing of the dregs in the wine cups on hearing steps at the main doorway. A servant of the corregidor, de-iig'hted at being ajble to spoil his sport, uttered in a sonorous voice:

"Their lordship and ladyship, the Marquis of Castello-Rotondo and the Marchioness of Ditto," and, in a lower voice: "Comrade, you are to show them to Don Jose, your master, as soon as the function is over in the chapel."

The domestic looked with amusement on the old gentleman and his lady, another wrinkled dame relic of the previous reign, who had plastered out the creases without canceling them, and rouged without the irritation becoming a blush, and blackened around her sunken eyes without bringing them anew to the front.

"Where on earth can they have brought u's, by the marquis' wish?" inquired the old noble, disdaining to question the menial.

"Is it a prison?" counter-queried the lady, scanning the vault and barred windows with awe.

Her lord had made the round of the table and examined with a lens set in his canehead, the residue of the more substantial part of the feast.