The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction (16 page)

Read The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction Online

Authors: Rachel P. Maines

Tags: #Medical, #History, #Psychology, #Human Sexuality, #Science, #Social Science, #Women's Studies, #Technology & Engineering, #Electronics, #General

R. J. Lane, who wrote about the English spa Malvern in 1851, quotes a male patient as saying that “the ladies are bolder-like with the wet sheets and Douches, and that, than the gentlemen.” Malvern at this time used the Priessnitzian douche, a gravity-powered fall of water from a cistern eighteen feet overhead. Lane, evidently in awe of women’s enthusiasm for the effects of hydrotherapy, mentions a lady who took the douche in the form of Niagara Falls, a sixty-foot fall at that point, and remarked, with some understatement, that “the Water Cure commends itself to the ladies.” The douche, which he himself seems to have regarded with some trepidation, he reports as “so powerful a stimulant, that persons are frequently known, on coming out of the douche, to declare that they feel as much elation and buoyancy of spirits, as if they had been drinking champagne.”

27

I shall have more to say about this elation later. Refinements were added as the century progressed. In 1867 the water cure at Matlock Bank in England had warm-water douche treatments for women plus electrotherapy and electric-bath installations. About 2,000 patients a year were treated there, of both sexes but with women predominating.

Another English spa of the second half of the nineteenth century provided horseback exercise, a traditional treatment for hysteria, to its women patients as an adjunct to hydrotherapy.

28

The companions and families of these patients often participated in the pleasures of the spa and its local service businesses.

29

After therapeutic douches were installed at Bath in the 1880s, over 80,000 bathers converged on Britain’s most famous spring to sample the latest hydriatic appliances.

30

Even the formerly disapproving traditional physicians were sometimes forced to give ground on the appeal of hydrotherapy to patients. W. B. Oliver, writing in the prestigious London medical journal

Lancet

in 1896, said of hydriatic massage that “the mechanical agency of percussion and vibration” of the water was modified by its temperature, so that when the jets of water strike the surface of the skin or “when it is applied in the form of a traveling douche accompanied by a vibratory form of massage, the vasomotor system is much more powerfully affected than by any form of still bathing.”

31

The douche was one of many therapies for hysteria in use at the Salpêtrière in the 1890s, when Freud was a visiting student there; Gilles de la Tourette reports that it was applied locally to the “hyperaesthetic” areas on the “front of the trunk.”

32

Walter McClellan, who practiced hydrotherapy at Saratoga Springs in the early twentieth century, describes douche therapy as “a current of water directed against the surface or into a cavity of the body.” He recommends supplies of both hot and cold water with a mixing valve, and a “hose or nozzle for projecting the stream of water onto the patient’s skin,” preferably one with enough pressure so that the water “may be projected from a distance of 10 to 15 feet.”

33

Water at a lower pressure could be applied from the sides. Although McClellan’s account is dated 1940, it is consistent with illustrations of the douche dating from the 1860s through the early twentieth century (see figs. 10, 11, and 12).

34

Americans seized on the spa concept with their characteristic enthusiasm for marriages of health with luxury and good living. So convivial were nineteenth-century American spas that a good many of their visitors did not even pretend to an affliction.

35

Alexander MacKay wrote in the 1840s that “of the vast crowds who flock annually to Saratoga, but a small proportion are invalids.”

36

Marietta Holley’s 1887

Samantha at Saratoga

does not even mention the baths, although perhaps Holley intended to omit any reference to such questionable practices as douche therapy. Samantha and her companions primly drink water in the Pump Room, with all their fashionable clothes on, and admire their luxurious surroundings.

37

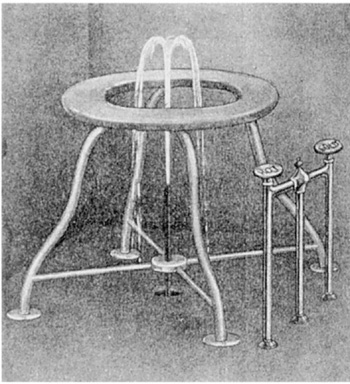

F

IG

. 10. The ascending douche at Saratoga, about 1900. From Guy Hinsdale,

Hydrotherapy

(Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1910), 224.

Although Austria claims credit for commercializing hydrotherapy in the nineteenth century, there is considerable evidence that American spas were thriving even before Priessnitz initiated his famous medical entrepreneurship. The travel author James Stuart said that “fifteen hundred people have been known to arrive in a week” at the spas at Saratoga and Ballston Springs, New York.

38

Hot mineral springs, however odoriferous, were the most popular, but even cold-water springs repaid hydropathic entrepreneurship.

39

New York State was a leader in the nineteenth-century spa industry, with a reported one-third of all United States water cures in 1847.

40

Saratoga remained New York’s most fashionable water cure until the early years of the twentieth century, with its

added attractions of a nationally famous racetrack and casino. The town also had, by the 1860s, a remarkably dense population of physicians, some of whom, like J. A. Irwin, made international reputations for themselves in hydrotherapy.

41

Women were the most visible, and probably the most profitable, patients at these establishments.

42

At Round Hill Water-Cure Retreat, for example, Halsted used Taylor mechanisms in treating chronic diseases of women to produce “statuminating vitalizing motion.” The New Hygienic Institute in New York City advertised in 1858 “the Swedish Movement Cure, Turkish baths, electric baths, vapor baths, water-cure, machine vibrations, lifting cure, magnetism and healthful food.” At some spas the patient’s circulation was stimulated by flogging with wet towels or sheets.

43

Writing of these establishments in 1984, historian Kathryn Sklar asserted that “sexual release through genital stimulation was a rudimentary water cure experience for women.”

44

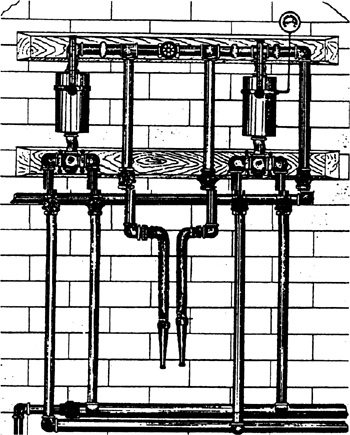

F

IG

. 11. Pope model of douche equipment, about 1900. From Curran Pope,

Practical Hydrotherapy: A Manual for Students and Practitioners

(Cincinnati: Lancet-Clinic, 1909).

From Ballston Springs (now Ballston Spa), New York, near the famous springs at Saratoga, we have the journal of a young woman, Abigail May, who eventually died of the disease (probably cancer) for which she had gone to the spa. The water cure seems to have brightened her last illness, however, despite the constant pain she suffered, although it had no curative effect. She says of her first encounter with the douche that it was difficult to summon the courage, but that “taking care to have laudanum handy” she took the plunge. After the initial shock, “I scream’d merrily—so says Mama—for my own part I do not remember much about it—I felt finely for two hours after bathing.”

45

She went to the baths again on a Sunday with a friend, an experience of which she says that “I was so much pleased with the Bath that probably I staid in too long—for immediately on returning to the house I was sensible of feeling extremely weak and languid.”

46

Elation followed by drowsiness were frequently observed in douche and massage patients. Simon Baruch wrote in 1897 that the douche was “the most stimulating of all hydriatic applications” and went to say that “it is not necessary to dwell upon the fact that every physiological indication is fulfilled by the douche. The nerve centers are aroused, the respiration is deepened, the circulation is invigorated, the secretions are increased.” He was especially enthusiastic about the results of “douches upon the loins” in cases of hysteria and neurasthenia.

47

Edward Johnson, who thought that hysterics should have douche treatment every day for a month, remarked that even this intensive treatment regimen did not satisfy all of his patients, and that he experienced “difficulty … in keeping them within rational limits. As soon as they become sensible of decided improvement, they become enthusiastic—they think they can never have enough—that the more they get, the faster they will get well.” He describes his patients’ enthusiasm for the douche, “generally looked upon as the ‘lion’ of every hydropathic establishment,” and remarks that this type of treatment is the one most often recommended to friends: “so many pleasant marvels to recount at home, and to excite the wondering curiosity of friends and relations.”

48

Johnson seems here to attribute the exciting effects of the douche to a kind of hydriatic equivalent of a roller-coaster ride. Mary Louise Shew, who warned or perhaps

promised women that hydrotherapeutic methods would produce new and unexpected sensations, quoted Johnson’s description of douche patients in 1844, where he reports “the most intense impression which can be made by the application of cold water.” Women are advised that “it sometimes produces the most extraordinary effects, as weeping, laughing, trembling, &tc.”

49

Mary Gove Nichols wrote that the douche “is a very exciting application, acting powerfully upon the whole system,” recommended as a way of reducing congestion caused by “excessive indulgence of amativeness,” in the form of either intercourse or masturbation.

50

According to Nichols, the hydriatic douche restored tone and vigor to the female reproductive system. Her husband, Thomas Low Nichols, after discussing the many virtues of hydrotherapy as a general treatment, asserts that “there is one class of diseases to which the adaptation of the Water-Cure ought every where to be known, and no false delicacy will atone to my conscience for not giving them the prominence they deserve. I allude to the diseases of women.” He discusses the relative merits of inpatient and outpatient therapy, mentioning that his establishment serves women who come in only for “[wet-sheet] packs and douches” and notes that “coming from the douche, a patient feels like jumping over fences.”

51

James Manby Gully, a contemporary of the Nicholses, recommended the douche for “nervous headache” in women, which he considered one of the hysteroneurasthenic disorders. Gully liked to stimulate the spine with the jet of water first, then zero in on locations like “the loins.”

52

William H. Dieffenbach, an early twentieth-century advocate of hydriatic methods, endorsed a combination of hydrotherapy with manual massage and vibratory treatment, especially for hysteria and neurasthenia, which like his predecessors he considered related disorders. He thought that “conjugal incompatibility, sexual excess, masturbation, sexual continence, habits of over-indulgence in coffee, tea, tobacco, drugs and alcoholic beverages” contributed to neurasthenia and hysteria.

53

Apparently the etiological paradigm could accommodate either too much sex or too little, a theory quite appropriate to a treatment that produced orgasms perhaps not regularly achieved in conjugal expressions of “amativeness.” His contemporary Curran Pope also thought that applying the douche to the “inner surface of the thighs” was an effective treatment of the sequelae of “imperfect or unsatisfactory intercourse.”

54

Pope waxed

even more poetic than his colleagues on the merits of the douche in achieving patients’ compliance with therapy: “Douches are, as a rule, more agreeable to the majority of individuals than the other forms of hydriatic procedure … It sets the tissues in a vibration impossible to describe; experienced, it is never forgotten.” As far as Pope was concerned, the douche was unparalleled as a tonic. “Administered at high or low temperatures, under a strong pressure, it is capable of arousing the most sluggish and intolerant function of the body.” In melancholia, neurasthenia, hysteria, and “other nervous affections, there is no weapon equal to the douche in restorative power.”

55

Guy Hinsdale at the same period thought that menopausal women were especially good candidates for hydriatic treatment. “The asthenic physical condition,” he wrote, “the mental depression, the irritability, the nervousness, and especially the sleeplessness, are certainly relieved to a great extent by a judicious use of these carbonated saline baths.”

56