The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction (18 page)

Read The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction Online

Authors: Rachel P. Maines

Tags: #Medical, #History, #Psychology, #Human Sexuality, #Science, #Social Science, #Women's Studies, #Technology & Engineering, #Electronics, #General

Eight years earlier, Butler had been marketing his device primarily to professionals, recommending it for “nervous exhaustion,” for which massage upward from the feet, first gently and then kneading until “the skin [is] made thoroughly red.” He describes patient responses not unlike those reported for hydrotherapy: “The immediate effect of the treatment on these nervous patients, is that of a calmative; they seem infinitely relieved of something; what—they seem unable to describe. They often want to sleep.”

86

This device, Butler asserted, could be used by the patient herself “after a lesson or two”; by 1888 he seemed to perceive no need for professional intervention at any point.

87

Another home device manufactured by a New York City firm about 1900 was recommended to purchasers interested in “developing and hardening the bust”

88

(

fig. 15

). The Electrical Building at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 had an exhibition of electromedical devices, “Group 135” of the many new applications of electric power.

89

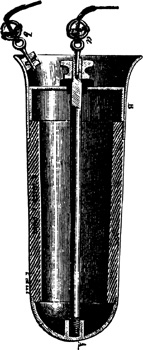

F

IG

. 14. “Excitateur vulvo-uterin” electrode, a faradization electrode illustrated in Auguste Élisabeth Philogène Tripier,

Leçons cliniques sur les maladies de femmes: Thérapeutique g

é

nérale et applications de l’électricité

à

ces maladies

(Paris: Octave Doin, 1883).

Physicians had mixed feelings about electromedical apparatus; John Girdner in

Munsey’s

of April 1903 quotes “a distinguished specialist” as saying that “at present medical electricity occupies a humbler position in applied therapeutics than it deserves” and goes on to say that “there are so many quacks and charlatans who deceive and rob the public by promises to cure disease with one electrical device or another that the medical profession is disposed to look askance at all such claims.”

90

John

Shoemaker, writing in 1907, seems to have had similarly grave reservations about electrotherapeutic devices in the hands of the unscrupulous. He says that electricity combined with massage, exercise, and good diet can be a useful regimen in some maladies, but that “without such therapeutic accessories, electricity, like massage, is very restricted in its usefulness and tends toward charlatanism.”

91

Electrical massage machinery was available to physicians from reputable suppliers like William H. Armstrong and Company of Indianapolis, which in 1901 manufactured both electrical rollers and a “portable combination massage instrument” called an “electro-spatteur” with a “vibrating fork” between the massage rollers.

92

Electrotherapeutic suppliers who sold equipment primarily to physicians were much less flamboyant in their advertising claims than consumer companies, and perhaps for this reason they retained their respectable medical reputation into the twentieth century.

93

Despite the odor of quackery that had begun to cling to electrotherapeutic devices for self-treatment by the late 1880s, they continued to be widely advertised and sold. The

Census of Manufactures

for 1905 noted that electrotherapeutic apparatus worth more than a million dollars was manufactured “in no fewer than 66 establishments, chiefly in Illinois and New York,” at a time when the total value of electrical household goods produced was about a fifth of this figure.

94

By 1914 the United States production of electrotherapeutic equipment was valued at more than $2.6 million.

95

As late as 1947, after X-ray equipment had been reclassified out of the category, “electro-therapeutic apparatus” was valued in the

Census

at $7.6 million.

96

These statistics were not, however, disaggregated by sales to consumers versus those to physicians, and figures were not provided on the number of units represented by the total values of manufactured goods. Clearly, the questionable character of these devices did not interfere significantly with sales.

The United States Battery Agency, for example, advertised in 1889 in

Dorcas Magazine

, to an almost exclusively female readership of embroiderers and other needle artisans, “All Physicians Agree that every family should have an Electric Battery in their house.” In the illustration, electrodes for every conceivable bodily orifice are depicted as accessories to the device.

97

Less ambitious was the Oxydonor of 1902, a “hydro-electrization” device for the home that had the additional advertised feature of adding healthful qualities to the air by producing ozone.

98

Instant beauty for women and restoration of head hair to men were among the miracles attributed to home electromedical devices by their advertisements.

99

Violet ray devices, which used electricity merely to generate light and heat in their brilliant purple electrodes, were reportedly less startling than “faradization” in their effects on the patient. The advertising stated that “a huge voltage of electricity is obtained and applied to the body or hair but without any shock whatever, and the only sensation being a pleasant warmth.”

100

Like the electric battery described in

Dorcas

, the violet ray came with a formidable set of attachments appropriate to the various orifices, and some of them combined vibratory capabilities and ozone generation with the allegedly therapeutic effects of violet light. One of these was made by Lindstrom, a vibrator manufacturer, and marketed in

Popular Mechanics

as an analgesic device, presumably to a mostly male readership.

101

F

IG

. 15. “Developing and hardening the bust” with electricity, about 1900.

MECHANICAL MASSAGERS AND VIBRATORS

Soon after train travel became a standard feature of industrialized life in the nineteenth century, it became the focus of an iatromachy over whether it was good or bad for women, primarily because it subjected them to vibration.

102

As we have seen, many physicians of earlier centuries thought the vibration of horseback riding and carriages benefited hysterics: Soranus, Paré, Sydenham, and others prescribed rocking, riding, and even dancing in addition to massage or marriage.

103

Charles Meigs in 1854 recommended that women enhance their “pelvic determination” of blood by “galloping on horseback, which powerfully develops it.”

104

Krafft-Ebing and George Beard both reported that some of their male patients were aroused to orgasm by equitation, and historians John Haller and Robin Haller report that horseback riding was one of the nineteenth-century treatments for impotence.

105

The movement of a railroad car clearly provided a similar but perhaps more intense experience of the same kind.

106

Predictably, this enhanced intensity was applauded by some physicians and deplored by others as a kind of overdose of physical therapy, which was thought to produce arousal or orgasm in women travelers. Charles Malchow thoughtfully provided directions on the posture most conducive to achieving this effect in a work that by 1923 had gone through six editions and twenty-seven printings. After noting that riding in vibrating vehicles such as railway carriages “sometimes occasions excitement, especially when sitting so as to be leaning forward” and could produce sexual arousal in women, he warns that “riding a bicycle or running a sewing machine tends, by the movements of the lower limbs and the friction occasioned, to sometimes produce such a condition of the genital organs as to lead to excitement and even orgasm.”

107

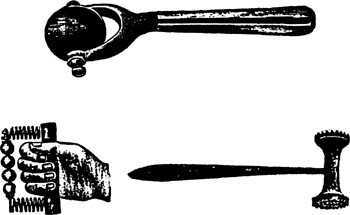

F

IG

. 16. Nineteenth-century muscle beaters.

He was not alone in expressing concern about the vibration and thigh rubbing associated with the use of pedal-operated sewing machines.

108

Later in the century, some physicians suspected that bicycles overstimulated women in the same way.

109

Haller and Haller tell us that “a physician from Tennessee reported that one of his patients took up the bicycle for the purpose of masturbation and admitted to him that ‘it was no uncommon thing … to experience a sexual orgasm three or four times on a ride of one hour.’”

110

Robert William Taylor, who wrote

A Practical Treatise on Sexual Disorders of the Male and Female

at the turn of the century, was convinced that horseback riding, sewing machines, and bicycles all encouraged masturbation in women.

111

We know little about how and how often nineteenth-century women masturbated, but there is more than ample documentary evidence that their male physicians expended considerable mental energy on the subject.

Russell Thacher Trail, a hydropathic physician and a colleague of John Harvey Kellogg, wrote in 1863 of the importance of physical therapies in diseases of women, which he said were otherwise very difficult to treat: “They are confessedly the

opprobrium medicorum

of the Profession, although not less than three-quarters of the business of modern

physicians is in prescribing for them.” For these ailments, Trall recommends “walking, dancing, jumping the rope, horseback riding &c” as active exercises, with “carriage-riding, rubbing and kneading the abdominal muscles” as “examples of appropriate passive exercise.”

112

Jean-Martin Charcot at the Salpêtrière, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, was one of the endorsers of rail travel for hysteroneurasthenic disorders and is said to have sent some of his patients on long trips over rough trackbeds for their health. He and his colleagues, however, eventually hit on the idea of shaking their patients in place, with various devices ranging from vibrating helmets to jolting chairs.

113

A number of variations on this theme were eventually devised, including chairs on springs that the patient operated by pulling two side levers (see

fig. 17

) and an electrical attachment for a rocking chair patented by Charles E. Hartelius in 1893, in which the rocking motion sent an electrical current through the patient.

114

John Harvey Kellogg’s Good Health catalog of therapeutic appliances in 1909 offered physicians a vibratory chair, a vibrating bar, a trunk-shaking apparatus (like those used today in weight-loss studios), apparatus for percussion and mechanical kneading, and a very impressive electromechanical “centrifugal vibrator.”

115