The Toilers of the Sea (26 page)

His voice took on all the solemnity he could muster:

“Mess Lethierry, let us not part without reading a page from the Holy Book. We can obtain enlightenment on the various situations in life from books. For the profane there are the

sortes vergilianae;

believers take their instruction from the Bible. The first book that comes to hand, opened at random, may give us counsel; but the Bible, opened at random, offers us a revelation. It affords benefit particularly to those in affliction. Unfailingly the holy scriptures will offer balm for their troubles. In presence of the afflicted we should consult the sacred book, not selecting any particular passage but reading with an open heart whatever page it opens at. What man does not choose, God chooses. God knows what we need. His invisible finger is on the passage that we find by chance. Whatever the page, it will unfailingly bring us enlightenment. Let us not seek any other light, but hold fast to Him. It is a message received from on high. Our destiny is mysteriously revealed to us in the text thus sought for with confidence and respect. Let us listen and obey. Mess Lethierry, you are in sorrow, and this is the book of consolation; you are sick, and this is the book of health.”

Dr. Hérode undid the clasp of his Bible, slipped a finger at random between two pages, laid his hand for a moment on the open book, paused as if in prayer, and then, lowering his eyes, began to read with an air of authority.

This was the passage he had chanced on:

“And Isaac came from the way of the well Lahairoi; for he dwelt in the south country.

“And Isaac went out to meditate in the field at the eventide; and he lifted up his eyes and saw, and, behold, the camels were coming.

“And Rebekah lifted up her eyes, and when she saw Isaac she lighted off the camel.

“For she had said unto the servant, What is this man that walketh in the field to meet us? . . .

“And Isaac brought her into his mother Sarah's tent, and she became his wife; and he loved her.”

156

Ebenezer and Déruchette looked at each other.

PART II

GILLIATT THE CUNNING

BOOK I

THE REEF

I

A PLACE THAT IS HARD TO REACH AND DIFFICULT TO LEAVE

The reader will have guessed that the boat seen at a series of points on the west coast of Guernsey at different times on the previous evening was Gilliatt's paunch. He had chosen to make his way down the coast through the passages between the rocks and reefs: it was a perilous route, but it was the most direct. His sole concern had been to take the quickest way of reaching the wreck of the Durande. Shipwrecks brook no delay; the sea makes urgent demands, and the loss of an hour might be irreparable. He was anxious to go to the rescue of the ship's engines as quickly as possible.

He had been concerned to get away from Guernsey without drawing attention to his departure, and had left in the manner of an escaping prisoner. It was as if he was trying to hide. Rather than pass in sight of St. Sampson and St. Peter Port, he avoided the east coast, slipping instead down the other side of the island, which is relatively uninhabited. When passing between the rocks it was necessary to use the oars. But Gilliatt worked the oars in accordance with the laws of hydraulics, entering the water without violence and leaving it without haste; and in this way he was able to proceed on his way in the darkness as rapidly and as quietly as possible. Anyone seeing him might well have thought that he was up to no good.

The truth is that, launching himself headlong on an enterprise that looked pretty nearly impossible, and risking his life with the odds heavily stacked against him, he was afraid of competition from some rival.

As day was beginning to break those unknown eyes that are perhaps open somewhere in space could have seen, at one of the spots in the middle of the sea where there is most solitude and most danger, two objects with an ever decreasing interval between them, one drawing closer to the other. One of them, almost imperceptible in the mighty surge of the waves, was a sailing boat, and in that boat there was a man: it was Gilliatt's paunch. The otherâimmobile, black, of colossal sizeârose out of the sea in fantastic silhouette. Two tall pillars reared up from the waves into the void, supporting a kind of crosspiece that served as a bridge between their summits. This crosspiece, so shapeless when seen from a distance that it was impossible to say what it was, combined with its supporting piers to form a kind of doorway. But what was the purpose of a doorway in this waste, open in all directions, that is the sea? It was like some titanic dolmen set up there in the midst of the ocean by some magisterial imagination and erected by hands that were accustomed to build on a scale proportionate to the abyss. Its eerie outline stood out against the light sky.

The morning light was growing stronger in the east, and the whiteness of the horizon deepened the blackness of the sea. Opposite this, on the other side of the horizon, the moon was setting.

These two pillars were the Douvres. The shapeless mass caught between them, like an architrave borne on the jambs of a door, was the Durande.

This reef, holding its prey, as if showing it off, was terrible to behold. Inanimate objects sometimes display a somber, hostile ostentation directed against man. There was defiance in the attitude of these rocks. They seemed to be waiting for something.

It was a scene of pride and arrogance: the vessel defeated, the abyss triumphant. The two rocks, still dripping with water after yesterday's storm, were like two combatants sweating after their exertions. The wind had died down, there were quiet ripples on the sea, and the presence of jagged rocks just under the surface was suggested by the plumes of foam that rose and fell gracefully above them. From the open sea came a sound like the murmuring of bees. Everything around was level except the two Douvres, towering up vertically like two black columns. Up to a certain height they were hairy with seaweed. Their sheer flanks had the sheen of armor. They seemed ready to reengage in combat. It was borne in on anyone seeing them that their roots were in underwater mountains. They had an air of tragic omnipotence.

Usually the sea conceals its attacks. It maintains a deliberate obscurity. This incommensurable expanse of darkness gives nothing away. It is very rare for a thing of mystery to yield up its secrets. There is something of the quality of a monster in catastrophe, but in unknown quantity. The sea is both open and secret; it hides, and is not anxious to divulge its actions. It brings about a shipwreck and then covers it over; it swallows up its victims out of a sense of shame. The waves are hypocrites: they kill, steal, conceal stolen property, plead ignorance, and smile. They roar, and then they bleat.

157

It was very different here. The two Douvres, raising the dead Durande above the waves, had an air of triumph. It was like two monstrous arms emerging from the abyss and displaying to the storms this corpse of a ship. It was like a murderer boasting of his achievement.

To this was added the sacred awe of the hour. The dawn has a mysterious grandeur, made up of a remnant of the dreams of night and the first thoughts of day. At this uncertain moment there are still specters about. The huge capital

H

formed by the two Douvres linked by the crossbar of the Durande stood out against the horizon in a kind of crepuscular majesty.

Gilliatt was wearing his seagoing clothesâa woolen shirt, woolen stockings, hobnailed shoes, knitted pea-jacket, trousers of rough, coarse material, with pockets, and one of the red woolen caps then worn by sailors, known last century as galley caps.

He recognized the Douvres reef and steered toward it.

The Durande was the very opposite of a ship sent to the bottom: she was a ship suspended in midair. It was a strange kind of salvage that Gilliatt was undertaking.

It was broad daylight when he arrived off the reef. As we have said, there was very little movement on the sea. The only agitation on the water came from its confinement between the rocks. In any channel, large or small, there is always some lapping of the waves. Within a strait the sea always has a covering of foam.

Gilliatt approached the Douvres with extreme caution, taking frequent soundings.

He had some cargo to unload. Accustomed as he was to frequent absences from home, he always had his emergency supplies ready for departure: a sack of biscuit, a sack of rye flour, a basket of salt fish and smoked beef, a large can of fresh water, a Norwegian chest painted with flowers containing some coarse woolen shirts, his oilskins and tarpaulin leggings and a sheepskin that he wore at night over his pea jacket. When leaving the Bû de la Rue he had quickly stowed all this in the paunch, together with a loaf of fresh bread. In his haste to get away the only tools he had taken with him were his blacksmith's hammer, his ax and hatchet, a saw, and a knotted rope with a grapnel at the end. If you have a ladder of this kind and know how to use it, you can tackle the most difficult climbs, and with it a good sailor can scale the steepest rock face. Visitors to the island of Sark can observe what the fishermen of Havre Gosselin are able to do with a knotted rope.

Gilliatt's nets and lines and other fishing tackle were also in the boat. He had taken them on board from force of habit, without thinking; for to carry out his enterprise he was going to spend some time in an archipelago of rocks and shoals where there would be no scope for using them.

When Gilliatt arrived at the reef the sea was ebbing, which was a circumstance in his favor. The falling tide had left exposed, at the foot of the Little Douvre, a number of slabs of rock, level or gently sloping, not unlike the corbels supporting the flooring of a building. These surfaces, some narrow and some broader, were set at irregular intervals along the base of the great monolith and continued to form a narrow ledge under the Durande, whose hull protruded between the two rocks, caught as if in a vise.

These rock platforms were convenient for landing and surveying the position. The stores brought in the paunch could be unloaded and kept there for a time; but it was necessary to make haste, for the rocks would be exposed only for a few hours. When the tide rose they would again be submerged.

Gilliatt brought his boat in to these slabs of rock, some of them level and some sloping down. They were covered with a wet and slippery mass of seaweed, the sloping ones being even more slippery.

Gilliatt took his shoes off, sprang barefoot onto the seaweed, and moored the paunch to a spur of rock. Then he walked along the narrow ledge of rock until he was under the Durande, looked up and examined her.

The Durande was wedged in between the two pillars of rock, suspended some twenty feet above the water. It must have been a very heavy sea that cast her up so high.

To seamen such violence of the waves is nothing new. To take only one example, on January 25, 1840, in the Gulf of Stora,

158

the last violent wave of a storm tossed a brig right over the wreck of a corvette, the

Marne,

and embedded it between two cliffs.

There was in fact only half of the Durande caught between the Douvres. She had been snatched from the waves and, as it were, uprooted from the water by the hurricane. The violence of the wind had buckled the hull, the stormy sea had held it firmly in its grasp, and the vessel, pulled in opposite directions by the two hands of the tempest, had snapped like a lath of wood. The after part, with the engines and the paddle wheels, had been hoisted out of the sea and driven by all the fury of the cyclone into the narrow gap between the two Douvres as far as her midship beam and was held fast there. The wind had struck a mighty blow; in order to drive this wedge between the two rocks the hurricane had turned itself into a sledgehammer. The forward part of the Durande, carried away and buffeted by the blast, had smashed to pieces on the rocks below.

The hold, broken open, had discharged the drowned cattle into the sea.

A large section of the forward part of the ship's side was still attached to the after part, hanging from the riders of the port paddle box on a few damaged braces that could easily be struck off with an ax. Farther away, scattered about in crevices in the reef, could be seen beams, planks, rags of canvas, lengths of chain and debris of all kinds, lying quietly amid the rocks.

Gilliatt examined the Durande carefully. Her keel made a kind of ceiling over his head.

The horizon, its limitless expanse of water barely moving, was serene. The sun was rising in its pride from this vast circle of blue.

Every now and then a drop of water fell from the wreck into the sea.

II

THE PERFECTION OF DISASTER

The two Douvres differed from each other in both shape and size. The Little Douvre, which was narrower and curving, was patterned from base to summit with veins of softer brick-red rock that divided the interior of the granite into compartments. Where these veins surfaced there were cracks that would be helpful to a climber. One of these cracks, a little above the level of the wreck, had been gouged out and worn away by the breakers until it had become a kind of niche that could have housed a statue. The granite had a rounded surface and was soft to the feel, like touchstone, but was nonetheless hard for that. The Little Douvre ended in a point shaped like a horn. The Great Douvre, rising in an unbroken perpendicular mass, had a smooth, polished exterior, as if hewn by a sculptor, and looked as if it were made of black ivory. Not a hole, not an irregularity in its smooth surface. Its steep sides were inhospitable; a convict could not have used it to help in his escape, nor a bird to make its nest. The summit was flat, like that of the Homme; but it was totally inaccessible. It was possible to climb the Little Douvre, but not to find lodging on the top; the Great Douvre had room enough on the top but was unclimbable.

After his first survey Gilliatt returned to the paunch, landed her cargo on the broadest of the rock ledges above the water, rolled up his modest stores and equipment in a tarpaulin, ran a sling around the bundle, with a loop for hoisting, and pushed it into a recess in the rocks where it was out of reach of the waves. Then, clutching the Little Douvre and clinging with hands and feet to every projection and every cranny in the rock, he climbed up to the Durande, stranded in midair, and, coming level with the paddle boxes, sprang onto the deck.

The interior of the wreck was a grievous sight. The Durande bore all the marks of a frenzied attack. She had suffered a fearful rape at the hands of the storm. A tempest behaves like a band of pirates. A shipwreck is a vicious attack on a vessel's life. Cloud, thunder, rain, wind, waves, and rocks are an abominable gang of accomplices in crime.

The scene on this dismantled deck suggested that the Durande had been trampled into ruin by the furious spirits of the sea. Everywhere there were marks of their rage. Bizarrely twisted ironwork bore witness to the frantic violence of the wind. The between decks were like the cell of a madman who had broken up everything in it.

No wild beast is as ruthless as the sea in tearing its prey to pieces. Water has countless claws. The wind bites, the sea devours; waves are voracious jaws. Objects are torn off and destroyed in the same movement. The ocean strikes as smartly as a lion.

What was remarkable about the destruction of the Durande was that it was so detailed and meticulous. It was as if she had been viciously dissected. Much of the damage looked as if it had been done on purpose. Anyone observing would be tempted to think, What deliberate wickedness! The torn planking seemed to have been fretted into shape. Ravages of this kind are characteristic of the cyclone. It is the caprice of that great devastating force to shred and diminish whatever lies in its path. A cyclone has the refined cruelty of an executioner. The disasters that it brings about are like tortures. One might think it harbored a grudge against its victims; it has the intense ferocity of a savage. In exterminating its victims, it also dissects them. It torments them, it revenges itself on them, it takes pleasure in destructionâshowing in all this a certain pettiness of spirit.

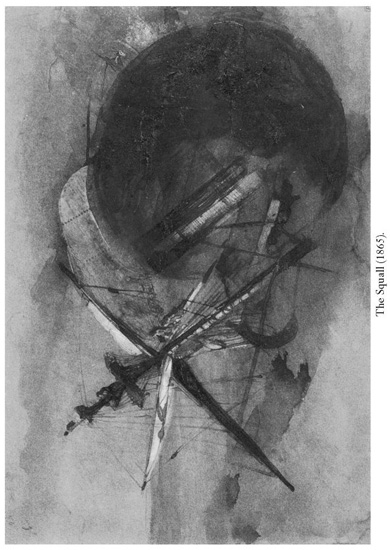

Cyclones are rare in our climes, and are all the more redoubtable for being unexpected. A rock in their path may become the pivot of a storm. The squall had probably formed a spiral over the Douvres and on striking the reef had turned into a whirlwind, which had tossed the Durande so high up between the rocks. In a cyclone a ship caught by the wind weighs no more than a stone in a sling.

The Durande had suffered the same kind of wound as a man cut in two; it was a torso torn open to release a mass of debris resembling entrails. Ropes swung free, trembling; chains dangled, shivering; the fibers and nerves of the vessel were exposed and hung loose. Anything that was not totally shattered was disjointed; the remaining fragments of the nail-studded casing of the hull were like currycombs bristling with points; the whole ship was a ruin; a handspike was now no more than a piece of iron, a sound no more than a piece of lead, a deadeye no more than a piece of wood, a halyard no more than an end of hemp, a strand of rope no more than a tangled skein, a stay rope reduced to a thread. All around was evidence of tragic, pointless destruction. Everything was broken off, dismantled, cracked, eaten away, disjointed, cast adrift, annihilated. It was a ghastly pile of fragments that no longer belonged together. Everywhere was dismemberment, dislocation, and disruption, in the kind of disorder and fluidity that is characteristic of all states of confusion, from the mêlées of men that are called battles to the mêlées of the elements that are called chaos.

Everything was collapsing and falling away; the flux of planks, panels, ironwork, cables, and beams had been halted just at the great fracture in the hull, from which the least shock might precipitate it all into the sea. What remained of the vessel's powerful frame, once so triumphantâthe whole of the after part of the Durande, now suspended between the two Douvres and perhaps liable to fall at any momentâwas split wide open at various points, revealing the dark and mournful interior.

Down below the sea foamed, spitting in contempt of this wretched object.