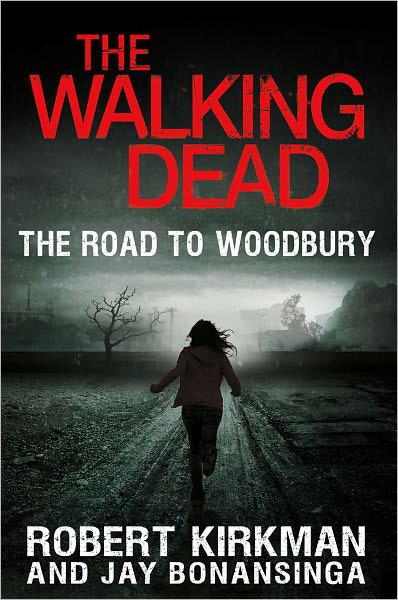

The Walking Dead: The Road to Woodbury

Read The Walking Dead: The Road to Woodbury Online

Authors: Robert Kirkman,Jay Bonansinga

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

Dedicated to Jilly (

L’amore della mia vita

)

—Jay Bonansinga

For all the people who have made me look far more talented than I actually am over the years: Charlie Adlard, Cory Walker, Ryan Ottley, Jason Howard, and of course … mister Jay Bonansinga

—Robert Kirkman

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Robert Kirkman, David Alpert, Brendan Deneen, Nicole Sohl, Circle of Confusion, Andy Cohen, Kemper Donovan, and Tom Leavens.

—Jay Bonansinga

For my father, Carl Kirkman, who taught me the value of working for yourself and showed me what someone can accomplish if they work hard and focus on what they want to achieve. And for my father-in-law, John Hicks, who gave me the confidence to take the plunge and quit my day job and strike out on my own. I owe a lot to both of you.

—Robert Kirkman

CONTENTS

Part I: Red Day Rising

Epigraph

Part II. This Is How the World Ends

Epigraph

Also by Robert Kirkman and Jay Bonansinga

PART 1

Red Day Rising

Life hurts a lot more than death.

—Jim Morrison

ONE

No one in the clearing hears the biters coming through the high trees.

The metallic ringing noises of tent stakes going into the cold, stubborn Georgia clay drown the distant footsteps—the intruders still a good five hundred yards off in the shadows of neighboring pines. No one hears the twigs snapping under the north wind, or the telltale guttural moaning noises, as faint as loons behind the treetops. No one detects the trace odors of putrid meat and black mold marinating in feces. The tang of autumn wood smoke and rotting fruit on the midafternoon breeze masks the smell of the walking dead.

In fact, for quite a while, not a single one of the settlers in the burgeoning encampment registers any

imminent

danger whatsoever—most of the survivors now busily heaving up support beams hewn from found objects such as railroad ties, telephone poles, and rusty lengths of rebar.

“Pathetic … look at me,” the slender young woman in the ponytail comments with an exasperated groan, crouching awkwardly by a square of paint-spattered tent canvas folded on the ground over by the northwest corner of the lot. She shivers in her bulky Georgia Tech sweatshirt, antique jewelry, and ripped jeans. Ruddy and freckled, with long, deep-brown hair that dangles in tendrils wound with delicate little feathers, Lilly Caul is a bundle of nervous tics, from the constant yanking of stray wisps of hair back behind her ears to the compulsive gnawing of fingernails. Now, with her small hand she clutches the hammer tighter and repeatedly whacks at the metal stake, grazing the head as if the thing is greased.

“It’s okay, Lilly, just relax,” the big man says, looking on from behind her.

“A two-year-old could do this.”

“Stop beating yourself up.”

“It’s not

me

I want to beat up.” She pounds some more, two-handing the hammer. The stake goes nowhere. “It’s this stupid stake.”

“You’re choked up too high on the hammer.”

“I’m what?”

“Move your hand more toward the end of the handle, let the tool do the work.”

More pounding.

The stake jumps off hard ground, goes flying, and lands ten feet away.

“Damn it!

Damn it!

” Lilly hits the ground with the hammer, looks down and exhales.

“You’re doing fine, babygirl, lemme show you.”

The big man moves in next to her, kneels, and starts to gently take the hammer from her. Lilly recoils, refusing to hand over the implement. “Give me a second, okay? I can handle this, I

can,

” she insists, her narrow shoulders tensing under the sweatshirt.

She grabs another stake and starts again, tapping the metal crown tentatively. The ground resists, as tough as cement. It’s been a cold October so far, and the fallow fields south of Atlanta have hardened. Not that this is a bad thing. The tough clay is also porous and dry—for the moment at least—hence the decision to pitch camp here. Winter’s coming, and this contingent has been regrouping here for over a week, settling in, recharging, rethinking their futures—if indeed they

have

any futures.

“You kinda just let the head fall on it,” the burly African-American demonstrates next to her, making swinging motions with his enormous arm. His huge hands look as though they could cover her entire head. “Use gravity and the weight of the hammer.”

It takes a great deal of conscious effort for Lilly not to stare at the black man’s arm as it pistons up and down. Even crouching in his sleeveless denim shirt and ratty down vest, Josh Lee Hamilton cuts an imposing figure. Built like an NFL tackle, with monolithic shoulders, enormous tree-trunk thighs, and thick neck, he still manages to carry himself quite gently. His sad, long-lashed eyes and his deferential brow, which perpetually creases the front of his balding pate, give off an air of unexpected tenderness. “No big deal … see?” He shows her again and his tattooed bicep—as big as a pig’s belly—jumps as he wields the imaginary hammer. “See what I’m sayin’?”

Lilly discreetly looks away from Josh’s rippling arm. She feels a faint frisson of guilt every time she notices his muscles, his tapered back, his broad shoulders. Despite the amount of time they have been spending together in this hell-on-earth some Georgians are calling “the Turn,” Lilly has scrupulously avoided crossing any intimate boundaries with Josh. Best to keep it platonic, brother-and-sister, best buds, nothing more. Best to keep it strictly business … especially in the midst of this plague.

But that has not stopped Lilly from giving the big man coy little sidelong grins when he calls her “girlfriend” or “babydoll” … or making sure he gets a glimpse of the Chinese character tattooed above Lilly’s tailbone at night when she’s settling into her sleeping bag. Is she leading him on? Is she manipulating him for protection? The rhetorical questions remain unanswered.

For Lilly the embers of fear constantly smoldering in her gut have cauterized all ethical issues and nuances of social behavior. In fact, fear has dogged her off and on for most her life—she developed an ulcer in high school, and had to be on antianxiety meds during her aborted tenure at Georgia Tech—but now it simmers constantly inside her. The fear poisons her sleep, clouds her thoughts, presses in on her heart. The fear makes her do things.

She seizes the hammer so tightly now it makes the veins twitch in her wrist.

“It’s not rocket science

ferchrissake

!” she barks, and finally gets control of the hammer and drives a stake into the ground through sheer rage. She grabs another stake. She moves to the opposite corner of the canvas, and then wills the metal bit straight through the fabric and into the ground by pounding madly, wildly, missing as many blows as she connects. Sweat breaks out on her neck and brow. She pounds and pounds. She loses herself for a moment.

At last she pauses, exhausted, breathing hard, greasy with perspiration.

“Okay … that’s one way to do it,” Josh says softly, rising to his feet, a smirk on his chiseled brown face as he regards the half-dozen stakes pinning the canvas to the ground. Lilly says nothing.

The zombies, coming undetected through the trees to the north, are now less than five minutes away.

* * *

Not a single one of Lilly Caul’s fellow survivors—numbering close to a hundred now, all grudgingly banding together to try and build a ragtag community here—realizes the one fatal drawback to this vacant rural lot in which they’ve erected their makeshift tents.

At first glance, the property appears to be ideal. Situated in a verdant area fifty miles south of the city—an area that normally produces millions of bushels of peaches, pears, and apples annually—the clearing sits in a natural basin of seared crabgrass and hard-packed earth. Abandoned by its onetime landlords—probably the owners of the neighboring orchards—the lot is the size of a soccer field. Gravel drives flank the property. Along these winding roads stand dense, overgrown walls of white pine and live oak that stretch up into the hills.

At the north end of the pasture stands the scorched, decimated remains of a large manor home, its blackened dormers silhouetted against the sky like petrified skeletons, its windows blown out by a recent maelstrom. Over the last couple of months, fires have taken out large chunks of the suburbs and farmhouses south of Atlanta.

Back in August, after the first human encounters with walking corpses, the panic that swept across the South played havoc with the emergency infrastructure. Hospitals got overloaded and then closed down, firehouses went dark, and Interstate 85 clogged up with wrecks. People gave up finding stations on their battery-operated radios, and then started looking for supplies to scavenge, places to loot, alliances to strike, and areas in which to hunker.

The people gathered here on this abandoned homestead found each other on the dusty back roads weaving through the patchwork tobacco farms and deserted strip malls of Pike, Lamar, and Meriwether counties. Comprising all ages, including over a dozen families with small children, their convoy of sputtering, dying vehicles grew … until the need to find shelter and breathing room became paramount.

Now they sprawl across this two-square-acre parcel of vacant land like a throwback to some depression-era Hooverville, some of them living in their cars, others carving out niches on the softer grass, a few of them already ensconced in small pup tents around the periphery. They have very few firearms, and very little ammunition. Garden implements, sporting goods, kitchen equipment—all the niceties of civilized life—now serve as weapons. Dozens of these survivors are still pounding stakes into the cold, scabrous ground, working diligently, racing some unspoken, invisible clock, struggling to erect their jury-rigged sanctuaries—each one of them oblivious to the peril that approaches through the pines to the north.

One of the settlers, a lanky man in his midthirties in a John Deere cap and leather jacket, stands under the edge of a gigantic field of canvas in the center of the pasture, his chiseled features shaded by the gargantuan tent fabric. He supervises a group of sullen teenagers gathered under the canvas. “C’mon, ladies, put your backs into it!” he barks, hollering over the din of clanging metal filling the chilled air.

The teens grapple with a massive wooden beam, which serves as the center mast of what is essentially a large circus tent. They found the tent back on I-85, strewn in a ditch next to an overturned flatbed truck, a faded insignia of a giant paint-chipped clown on the vehicle’s bulwark. Measuring over a hundred meters in circumference, the stained, tattered canvas big top—which smells of mildew and animal dung—struck the man in the John Deere hat as a perfect canopy for a common area, a place to keep supplies, a place to keep order, a place to keep some semblance of civilization.