The World of Caffeine (45 page)

Read The World of Caffeine Online

Authors: Bonnie K. Bealer Bennett Alan Weinberg

Camellia sinensis

can grow in climates ranging from Mediterranean to tropical and at altitudes from sea level to eight thousand feet, but flourishes at altitudes of between two thousand and sixty-five hundred feet and in areas receiving moderate rainfall. The most commonly cultivated variety,

Camellia sinensis assamica,

or Assam tea, has little resistance to cold and grows well only in tropical areas. The Assam tea plant, which is considered a tree, has large leaves, about ten inches long, and, left uncultivated, can grow to a height of fifty feet. These tough little trees are hard to kill, and in China they frequently live longer than one hundred years. China tea, or

Camellia sinensis sinensis,

which has been commercially cultivated for nearly two thousand years, offers lower yields than Assam tea but produces a more delicately flavored beverage. The China tea plant is considered a bush rather than a tree because it is multistemmed, even though it attains a natural height as great as twenty feet. It has stiff, serrated fourinch leaves. China tea can tolerate brief cold periods and thus higher altitudes than Assam tea. In the 1800s China tea was cultivated in South Carolina, but the plantations were abandoned because high labor costs made them unprofitable. However, many wild plants still survive in this area.

Because tea bushes grow luxuriantly in a climate that is hot and wet, preferably with at least one hundred inches of rainfall per year, tea is grown commercially in the humid regions surrounding the equator. Although in China it is often still grown on patches of wasteland, as recommended by the ancient sage of tea, Lu Yü, it flourishes best in rich soil. Like coffee trees, tea bushes usually grow best and produce better tea in the shade of trees planted nearby to protect them from the scorching tropical sun. In mountainous areas below six thousand feet, the leaves develop slowly, are more tender, and produce a higher concentration of caffeine.

Lu Yü’s eighth-century

Classic of Tea

mentions a wild tea tree in Szechuan so large that two men with outstretched arms were required to encircle its trunk. In recent times many such wild trees, towering up to forty feet, have been found in southern and eastern Szechuan and in Yunnan and Guizhou provinces along the lower reaches of the Lancang, Nu, Qu, Pan, and Hongshui Rivers. A King Tea Tree, the largest ever discovered, was found growing wild in 1939. It is judged to be more than seventeen hundred years old and is still growing in the forested Xishuangbanna region of Yunnan near the Burma border. It is 108 feet tall, with a main trunk more than a yard in diameter.

19

In nature, tea cross-pollinates, a gene-shuffling process subject to the inherent uncertainty of any sexual reproduction. The only way growers can reproduce a bush exactly is with a technique known as “layering,” in which a branch still on a living bush is bent and buried until it roots. Although this method effectively clones superior plants, it is expensive, and most tea planters still take their chances with shrubs grown from seeds in nursery beds. After about six months, six-inch seedlings are transplanted to the tea garden. The young plants are set out in rows at three- to six-foot intervals and left to grow unimpeded for two years. A fairly level tea garden will be tenanted by three to four thousand bushes per acre.

Following three additional years of careful tending, the plants are fully developed and ready for their first plucking. Thereafter, each will be pruned to a height of three to five feet and plucked. Pruning is vital to the production of tea because it stimulates the growth of flush, the tender young leaves from which tea is made. If left to its natural course, the plant would

stop yielding flush, the sap passages would gradually become occluded, the twigs would harden into wood, and the existing leaves would become larger and tougher until they became completely unsuitable for brewing. As James Norwood Pratt, in

A

Tea Lover’s Treasury,

explains with more melodrama, bathos, and empathy than is usual in botanical accounts:

Constant pruning and plucking keeps the bush desperately striving for full treehood and perpetually producing new leaves and buds…. The poor tea bush is kept in this state of unrelieved anxiety from about age 2 to something over 50, when its yield begins to decrease, and, to avoid labor and sorrow, it’s uprooted and replaced. It dies without once having been allowed to flower and seed.

20

Even under such grimly unremitting cultivation, each tea bush produces at most only ten ounces of finished dry leaf a year.

Both Assam and China tea plants are trimmed to waist height, not only to stimulate the bush, but to make plucking the leaves easier. Ideally, only young leaf shoots and the unopened leaf bud, rich in caffeine and the organic compounds that give tea its aroma and flavor, are harvested. Plucking only the young leaves without destroying the health of the plant is a highly skilled job. Superior tea results when only the growth bud, or “pekoe,” and the next youngest leaf are taken. Lower grades of tea are the products of “coarse” plucking, in which the bud, the first two leaves, and the old leaf below them are all taken, along with that much more of the twig. Unfortunately, to reduce costs, mechanical shearing, producing a coarse tea of uneven quality, is on the increase. For example, the Russians, who raise tea in Georgia north of the Caucasus, employ a self-propelled mechanical tea plucker of their own invention. However, the best teas are high-grown on terrain that precludes mechanization, and even industrialized countries like Japan and Taiwan still pluck their teas by hand. Because of improvements in cultivation and harvesting techniques, an acre in Assam that produced three hundred pounds of tea a hundred years ago may yield as much as fifteen hundred pounds today.

Despite all the efforts to bring tea planting to the West, only the Russian introduction became commercially important. In 1893, using the offspring of plants that had been planted in the botanical gardens of Sukahm, a Black Sea port, and which had been the subject of agricultural experimentation for almost fifty years, C.S.Popoff transported fifteen Chinese foremen and laborers to farm his estates and teach his Russian countrymen how to raise tea, thus instituting a crop that has been a valuable source of revenue for the region of Georgia ever since.

Like the cultivation of coffee, the cultivation of tea is fraught with many curiosities. In Sri Lanka, the Tamil-speaking Hindus who pluck tea leaves bury their dead between the tea rows.

21

It is said that in early China, tea pluckers were virgin girls under fourteen, who wore new gloves and a new dress daily.

22

They were required to abstain from eating fish and certain meats, so that their breath wouldn’t taint the flavor of the leaves, and to bathe before going to the fields, for a similar reason.

23

Tea will not grow for some time where lightning has struck or on the site of former human habitation—or so the Chinese farmers’ lore teaches.

24

(Theobroma cacao)

Cacao is the bitter powder made from the ground, roasted beans of the cacao tree

(Theobroma cacao)

called cacao or cocoa beans, with most of their fat removed. The family Sterculiaceae, to which the genus

Theobroma

belongs, has one other member of major economic importance,

Cola

.

“Theobroma”

is scientific Latin (from Greek roots) for “drink of the gods,” and the genus was so named by Linnæus in 1753

25

for the fact that the cacao tree was a sacred plant to the Aztecs, who cultivated it and used it in their religious rites. In 1502, when cacao seeds were brought back to Spain by Columbus, the cacao tree became the first caffeinated plant on record to reach Europe.

Twenty-two species of the genus

Theobroma

have been distinguished, but only

cacao

is raised commercially. Another species,

bicolor,

is grown in Latin American family gardens as a source of beans or of a sweet pulp used for confections, and in Mexico it is used to make a drink called

pataxte

or to adulterate more expensive chocolate. Genetic investigation of other species is being pursued in the hope of improving the cacao tree’s yield and increasing its resistance to disease.

According to the botanist José Cuatrecasas,

26

cacao originally grew wild from Mesoamerica to the Amazon basin. The trees in the intermediate areas died out, and, by the time human beings came to notice cacao, the northern and southern regions had evolved two distinct varieties. Both of these varieties of the species

cacao

are commercially cultivated:

criollo

(“native”), with long, pointed pods, which grows in Mexico and Central America, and

forastero

(“foreign”), with hard, round pods, which grows south of Panama. The Aztecs and Maya cultivated

criollo

exclusively, and its beans were the ones enjoyed by the seventeenth-century European aristocracy. The planting of

forastero

started with the Spanish conquerors.

Criollo

may have been the early favorite because its beans require little or no fermentation while

forastero

cacao must be fermented to make a palatable drink.

27

Like

Coffea arabica, criollo

has a distinctive, subtle flavor, but

forastero

has become the dominant variety worldwide, supplying more than 80 percent of the world’s chocolate, because, like

Coffea robusta,

it is more vigorous and produces a greater yield.

28

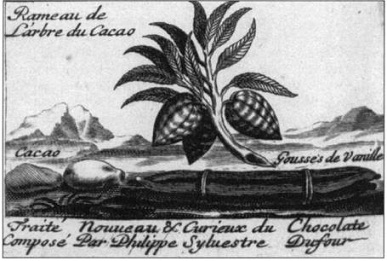

Engraving from Dufour,

Traitez Nouveaux.

This French engraving illustrates a branch from the cacao tree, two harvested cacao pods, and a vanilla pod. Vanilla was among the many ingredients added to flavor chocolate drinks. (The Library Company of Philadelphia)

Though

Theobroma

is endemic to Central and South America, principally to the upper Amazon and Orinoco river basins, it is grown today around the world between the twentieth parallels, except in the central and eastern parts of Africa, where poor soil and dry climate make its cultivation impossible. West Africa, including Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon, and the Ivory Coast, presents ideal conditions for cacao, and in consequence has become the largest regional exporter today, with a production of more than 750,000 tons of dried beans a year. Ghana was formerly the single top national producer in the world, with more than 400,000 tons a year, but because of political instabilities has yielded this rank to the Ivory Coast. In Latin America, Brazil is first, with 350,000 tons, followed by the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, and Mexico. Cacao is also now grown widely in the Far East, in Indonesia, Malaysia, and New Guinea.

Theobroma cacao

is an evergreen tree that, in the dense jungle habitat of the primary rainforest, is sparsely branched and can reach heights of fifty feet. However, when planted in unshaded plantations, it branches densely and rarely exceeds fifteen feet. Cacao trees begin to bear fruit after four or five years, attain full maturity in about ten years, and often continue bearing pods for more than sixty years. In periodic flushes throughout the year, cacao trees produce new leaves that quickly turn from a pinkish green to a deep green on the upper surface and a soft lighter green on the lower surface. The mature leaves, in two rows along the branches, are elliptical and may be as long as twenty inches.

After two or three years, each tree displays more than ten thousand small flowers, which grow on short stalks directly from the old wood of the trunk or main branches. These abundant unscented flowers, exhibiting a dazzling range of pastel colors, are pollinated by midge flies, although fewer than 5 percent produce mature pods, and fewer than twenty to fifty fully developed fruits appear at any one time. A fully grown pod is six to ten inches long and three to four inches thick and contains about thirty to fifty oval purple beans, each about one and one-half inches in diameter, surrounded by a pale pink pulp. As the fruit, or pod, ripens, it advances from green through a range of colors, including yellow, orange, red, and purple. Although the fresh beans are bitter, the sweet, pungent aroma and flavor of the whitish pulp that surrounds them attracts birds, monkeys, and other animals that split the pods, devour the pulp, and discard the seeds, scattering them widely throughout the jungle. Partly as a result of this foraging, cacao trees now grow wild in almost every corner of South America.

29

The techniques of harvesting and drying the beans have remained fairly constant for centuries. Each pod is cut from the tree with a machete, the worker careful to avoid damaging the flower beneath it. Within a couple of days, the pods are split open, usually by hand. Once the husks have been discarded, the fresh beans and pulp are mixed with yeast and placed in wooden boxes. During the following week, the beans, fermenring at temperatures up to 120 degrees Fahrenheit, are thoroughly transformed, until finally attaining much of their characteristic flavor. Following fermentation the beans are spread out in the sun to dry and raked several times a day for three to five days. Although wood-or oil-burning rotary dryers are sometimes used to speed the process, sun-dried beans have the richest flavor. In the process of drying, the beans acquire their universally recognized “chocolate brown” color.