Third Reich Victorious (33 page)

Three infantry corps of the 2nd Panzer Army, totaling some fourteen divisions, defended the line with the 5th Panzer Division in immediate support. Behind them stood Model’s 9th Army with its two full-strength Panzer corps. Von Kluge also had an additional five Panzer divisions in deep reserve. Aerial reconnaissance picked up Soviet troop movements to the east, allowing the troops some advance warning of the impending attack, but on the north face, the German defenders had no such warning.

Kutusov started on June 28 with the normal Soviet practice of sending their reconnaissance battalions into the German defenses to probe for weaknesses and redefine lines of advance. In addition to this activity, Stalin unleashed his “

relsovaya voina

” (war on the rail lines)—thousands of partisans armed with explosives attacked the rail lines leading in and out of the salient. Over 10,000 demolition charges went off, disrupting German movement and, Stalin hoped, pinning two German armies in the salient to be destroyed by his converging forces.

Early on June 29 the 11th Guards Army assaulted their portion of the line. Massing almost all their tanks and guns on a ten-mile stretch of the German defenses, the deluge devastated and overwhelmed two infantry regiments and the forty tanks that held that portion of the line. Despite counterattacks by the 5th Panzer Division, the assault penetrated almost six miles, just short of the German second line.

To the east, the Bryansk Front’s assault was far less successful. The German defenders, reinforced by corps antitank reserves, stalled the initial push by the 3rd and 63rd Armies, destroying over half their armor. The Soviet infantry barely gained two miles against these heavy losses. The commitment of the 1st Guards Tank Corps the following day also stalled quickly in the dense German defenses, and was stopped completely as the 2nd and 8th Panzer Divisions arrived to seal the penetration.

The second day of the attack saw the 11th Guards continue their success, committing the 1st and 5th Tank Corps to breach the second German line and gain another three miles. By July 1 three Panzer divisions, the 12th, 18th, and 20th, had arrived to blunt the advance. However, the success of the Western Front’s advance worked against it as its flanks were left open by the stalled drive coming from the east. The massed Panzers smashed the 5th Tank Corps and threatened to cut off the entire breakthrough. The Soviets countered by throwing the 50th Army into the breach, but it was not the mobile force they needed. The 4th Tank Army was still in transit.

On July 2 the Central Front opened its drive from inside the Kursk salient, with the 13th, 48th, and 70th Armies attacking. They met stiff resistance, even on their limited front, and barely made it through the first German line in a replay of problems farther north. The 2nd Tank Army, waiting for the breakthrough, was stalled in the open; Luftwaffe air strikes took a heavy toll on the waiting tanks. It took two full days for the Central Front’s infantry to hammer a hole large enough for the 2nd Tank Army to drive through. When it finally did, it ran into highly accurate antitank fire, mainly from the dug in 656th Antitank Detachment, made up of Elefant self-propelled antitank guns. These weapons—an 88mm gun in a turretless tank—proved deadly in long-range combat. The 2nd Tank Army’s 16th Tank Corps lost 75 percent of its strength—150 tanks—in a single engagement, while only killing three Elefants. As they reeled back from the losses, the Germans followed up with a counterattack by the remainder of the XLVII Panzer Corps.

For the next five days, the Soviets hammered at the Germans, but the fresh and mobile Panzer divisions stalled virtually every threat, striking at the flanks and forcing the Soviets to defend their small gains. During this period, German intelligence was stunned when aerial reconnaissance photographs showed two large tank formations closing in on the Orel battlefield. In addition, despite defeating the Mius and Izyum offensives, they began seeing massed movement south of Kursk near Belgorod, indicating another Soviet attack pending. It was becoming obvious that the Soviets had been able to mass far more combat power than the Germans ever suspected.

On July 3 the main Soviet attack began as Operation Rumiantsev opened. There was nothing fancy about these plans, authored by Georgi Zhukov himself. He massed almost five complete armies (5th Guards, 6th Guards, 53rd, 69th, and part of the 7th Guards) at the point of the main attack, backed by two tank armies, the 1st and 5th Guards. Two days after this attack began, two more armies would attack on their right; three days after that, two more armies on the left. Overall, three Soviet Fronts—Voronezh, Steppe, and Southwestern—concentrated 990,000 men, 12,000 guns, and 2,400 tanks at the point of decision.

Opposing them was Horn’s 4th Panzer Army and Army Detachment “Kempf.” Well-rested infantry manned the front lines, with the 7th Panzer Division in immediate support. There were multiple defensive lines established—Kharkov had seven protecting it from the north and three lines to the east. Belgorod, closest to the front, was protected by defensive lines and fortified heavily. Backing the infantry up was the mobile power that had been assembled for Zitadelle—the XLVIII and II SS Panzer Corps. Army Group South was missing only the two Panzer divisions sent successfully to destroy the breakthrough on the Mius River. Additionally, the 3rd SS Panzergrenadier Division “Totenkopf” had been temporarily detached from the II SS Panzer Corps to operate against the Izyum bridgehead. Altogether, though, the Germans fielded 350,000 troops and some 900 tanks.

When Zhukov attacked, the disparity in strength at the point of attack was decisive. The guns opened fire at 0500, the infantry struck at 0800, and by noon, a six-mile hole had been torn in the first German line. Both exploiting tank armies plunged into the hole, and by the end of the day had driven some fifteen miles into it. Zhukov’s infantry, however, lagged the advance by some nine miles as they dealt with the German defenses. This gap would widen over the coming days and create an opportunity that von Manstein could exploit.

When the massive blow fell near Kharkov, Hitler had been considering Army Group Center’s suggestion to withdraw from the Orel salient. His initial impulse was to say no, as he had many times before, but the Tunisian disaster still hung in his mind. With the Kharkov front suddenly ripped open, the reserves he could have used to hold Orel were unavailable. On July 4 he gave permission to von Kluge to withdraw to the Hagen line. Six days later, when the Allies invaded Sicily, the permission became an imperative order.

To the north, von Kluge and his army commanders still had the problem of the continual Soviet pressure and the approaching armor. Fortunately for them, Stalin and his generals made it easy. They committed each tank army separately as it arrived, allowing the Germans to use their interior lines to counter each threat.

The 3rd Tank Army arrived first from the east and, rather than exploit the shallow breach made by the 3rd and 63rd Armies, its commander, Gen. P. S. Rybalko, decided to force a separate breach. The attack, on July 6, was generally successful, with the momentum of the shock force carrying it over seven miles through German defenses, but casualties in men and equipment were heavy. Diverging directives from Stalin and his front commander further split up Rybalko’s diminished combat power. The orders left the tank army vulnerable to counterattacks by the 2nd and 8th Panzer Divisions that stopped each piece separately.

By the time the 4th Tank Army arrived and went into action on July 13, it was apparent to the Soviets that the Germans were evacuating the salient. They tried to step up the pressure to eliminate as much of the enemy strength as they could, but Stalin’s primary mobile force, the 2nd and 3rd Tank Armies, had been devastated—from a strength of 450 and 730 tanks respectively, each army now fielded fewer than sixty tanks. Pursuit by infantry was too slow to be effective. Thus the 4th Tank Army was sent in virtually alone. It ran into an ambush of hidden tanks and assault guns and lost 50 percent of its strength on the first day.

With the Soviets’ last mobile reserve blunted, the Germans completed their withdrawal by July 20, managing to take 53,000 tons of supplies out with them. They destroyed every military installation and burned grain crops as they went. The Soviets could point to a huge tract of land liberated in Operation Kutusov, but they had lost over 550,000 casualties and 80 percent of their armor. The Germans had been hurt too, losing almost half their tanks and guns, but the targeted armies of the offensive were intact and effective behind a strong defensive position.

To the south, Zhukov’s offensive continued as the two wing attacks started on time but barely made progress against German defenses. The added pressure, however, kept the German armies pushed apart and interfered with their effectiveness in dealing with the crisis. Zhukov’s infantry became embroiled for days around the towns of Graivoron and Borisovka, trying to encircle and destroy the elements of five German infantry divisions. Counterattacks by the 11th Panzer and “Grossdeutschland” Divisions held the escape routes open and got most of the troops out, though they were severely hampered by heavy artillery fire from the encroaching Soviets.

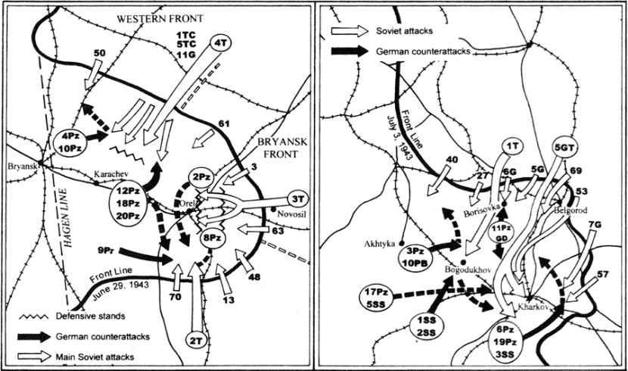

Map 11. Kutusov and Rumianstev Offensives

The rescue efforts around Borisovka delayed the German response to the invading tank armies, but ensured that the 1st Tank Army was operating with minimal infantry support. On July 10 two Panzergrenadier divisions, the 1st SS “Liebstandarte Adolf Hitler” and 2nd SS “Das Reich” launched a counterattack at the exposed Soviet spearhead near Bogodukhov. The next day the 3rd Panzer Division and 10th Panzer Brigade, with some 200 new Panther tanks, struck the embattled Soviets from the opposite flank. The new tanks showed they were superior to the enemy tanks they faced—when they worked. Far too many fell victim to mechanical failure. However, the two flank attacks shattered the 1st Tank Army and severely damaged the tank corps preceding the 40th Army’s advance that attacked the 3rd Panzer with a flank attack of its own.

While the 1st Tank Army was battling for survival, Zhukov set up his set-piece assault on Kharkov. He planned to have the 53rd Army and part of the 5th Guards Tank Army attack the city from the northwest, while the Southwestern Front’s 57th Army attacked it from the southeast. A direct frontal attack by the 7th Guards Army, and an encircling move by the remainder of the 5th Guards Tank Army, would force the Germans to evacuate the city or be trapped inside.

But the loss of the 1st Tank Army left the German mobile forces free to concentrate on the threat to Kharkov. The III Panzer Corps, recently arrived from the Mius battle, would move directly up the Donets from Izyum and attack the 57th Army in the flank with Totenkopf in support. Liebstandarte and Das Reich would attack the encircling tanks, and Army Group South’s main reserves, the 17th Panzer Division and 5th SS Panzer Wiking would attack the Soviet threat in the northwest.

The two sides collided on July 15. The next two days of swirling tank battles saw both sides lose heavily. But the concentrations that the Germans could throw at the exposed Soviet spearheads proved too much. A divided 5th Guards Tank Army took a toll on the attacking Germans, but was completely shattered, with 95 percent of its armor destroyed. Without an armored shield, the Soviet infantry units were forced to halt their own attacks and defend. Both the 57th and 7th Guards fell back after resisting the German assaults for several days, opening up the rest of Zhukov’s forces to flank attacks from the southeast. By July 21 the Soviet attack was spent. There was general movement back toward the river lines, but Soviet troops held multiple towns and villages, creating a patchwork of isolated islands of resistance in the sea of German armor. The Germans had little infantry strength to deal effectively with these isolated positions, and their armor was battered and exhausted.

The Soviets held on to some bridgeheads over the Donets, but the significant victory they were seeking fell terribly short. Two more carefully built-up tank armies had been ruined and over 2,000 tanks destroyed in three weeks of intense fighting. Another 480,000 men had fallen, nearly half during the pull-back and mop-ups. The Germans had suffered as well, losing 60 percent of their armor, but had taken the tremendous body shot the Soviets had prepared and stayed intact.

For now the East quieted down as both sides licked their wounds.

When the news that the Germans were cancelling their Kursk offensive to build a strategic reserve came out of Moscow, the Allies were stunned. Nervous intelligence officers tapped every source they had looking for signs that the Germans were moving more troops into Sicily. They identified Rommel’s new command in northern Italy but little else. Ultra gave no indications of major movements—but it had also given no warning of Zitadelle’s cancellation.

7

When the Soviets struck in the east and pinned the Germans down, Allied fears subsided and Husky continued.