This Great Struggle (48 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

Hood was just the man for desperate fighting. The tall, tawny-bearded Texan had graduated forty-fourth in the fifty-two-man West Point class of 1853 and had turned thirty-three years old during the campaign down from Dalton. He had first ridden to fame in the second year of the war as commander of the Texas Brigade of the Army of Northern Virginia, Hood’s Texas Brigade, as some still called it, renowned as the hardest-hitting unit of Lee’s army. From there Hood had risen to lead a division and suffered at Gettysburg a wound that paralyzed his left arm. Promoted to corps command and transferred to the Army of Tennessee in time for Chickamauga, Hood had taken a bullet in the right thigh that had necessitated amputation just below the hip. He now had to be helped into the saddle and strapped there to ride, but no one would ever question his combativeness. Queried by Davis as to Hood’s fitness to take the reins of the Army of Tennessee now with its back to Atlanta, Robert E. Lee responded that Hood was “a bold fighter, very industrious on the battlefield, careless off.”

2

Both Davis and Bragg believed that Hood was the man they needed for the present crisis or at least the best man they could get at the moment. On July 17 Davis sent orders by telegraph relieving Johnston of command and appointing Hood in his place. Hood’s letters to Davis over the preceding three months had helped to undermine Johnston with the president, but ultimately Johnston had been the author of his own downfall by refusing to risk a battle that might mar his reputation and by showing concern only for ensuring that everyone knew that the bad results achieved on his watch were not his responsibility. Whatever Hood’s intentions might have been in writing his letters, he was appalled to learn that he had been thrust into the command with the army backed up against Atlanta. First individually and then in concert with his two fellow corps commanders, he appealed first to Johnston to ignore the order, at least temporarily, and then to Davis, via telegraph, to rescind it. Neither complied, and Hood found himself irrevocably in command of an army in desperate circumstances.

THE BATTLES OF PEACHTREE CREEK AND ATLANTA

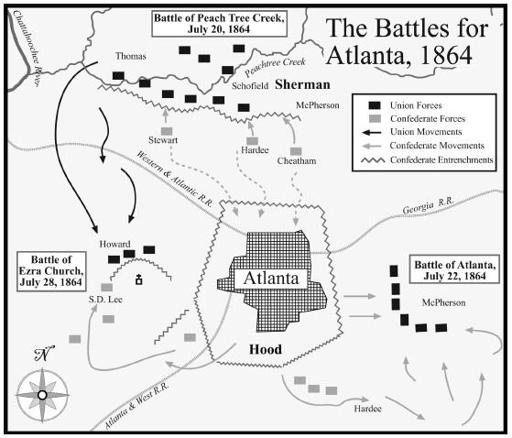

After several days of rest along the banks of the Chattahoochee, Sherman’s armies advanced once more toward Atlanta. Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland approached the city directly from the north, while McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee, again playing its role as Sherman’s whiplash, swung wide to the Union left to strike the Georgia Railroad near Decatur and then approach Atlanta from the east. Schofield’s Army of the Ohio advanced between its two larger partners, maintaining contact with both by its skirmishers. As had been the case most of the way from Dalton to the Chattahoochee, the Army of the Tennessee would be turning the Rebels, threatening to cut an important line of communication between Confederate forces in Georgia and Virginia.

As the movement was in progress, Sherman learned of the change of commanders on the Confederate side. He was not familiar with Hood, but his subordinates were. Thomas had been one of Hood’s instructors at West Point, and McPherson and Schofield had been his classmates there. The latter had even been his roommate and had coached the academically challenged future Confederate general through some of his more difficult mathematics courses. Hood was a fighter, the three generals assured Sherman, “bold to rashness” and very likely to attack someone at the first opportunity. Sherman was pleased. Johnston’s repeated slippery retreats had prevented Sherman from coming to grips with the Rebel host in Georgia on any but the most disadvantageous terms, with the Confederates firmly ensconced behind impregnable breastworks that Johnston obviously longed for Sherman to assault. True, Johnston had fallen back all the way to Atlanta in order to avoid any different sort of encounter with Sherman, but the result had been to deny Sherman the opportunity of fulfilling Grant’s orders to hammer the Army of Tennessee. Now, with Hood in command, Sherman was confident he would be able to get a stand-up fight out of the Rebels.

At about the same time Sherman was learning of Hood’s accession to command, Hood was learning that Sherman had turned him again. Like Johnston with each of Sherman’s turning movements, Hood now faced the choice of either fighting or retreating, but unlike Johnston, Hood never had the chance of retreating without giving up Atlanta. The necessity of the situation, the president’s obvious expectations, and his own nature all dictated Hood’s next move. The questions were where and when he would strike.

Hood’s answer came at 4:00 on the afternoon of July 20 in the form of an all-out assault of the Army of the Cumberland, which at that time had just finished crossing to the south bank of Peachtree Creek. Hood hoped to catch Thomas in the act of crossing the creek, giving the Confederates a numerical advantage against the part of the Army of the Cumberland already on the south bank and catching the Federals before they could dig entrenchments. It might have worked if it had been launched several hours earlier, and Hood had meant it to be. Confederate armies, by law, never had enough staff officers, so that it was always difficult for a commander to translate his ideas into action, often requiring him to invest much personal attention in preparations.

When Davis sought Lee’s advice about replacing Johnston with Hood, Lee had characterized Hood as being “careless” off the battlefield, and the fiery Texan’s lack of attention to detail was no doubt exacerbated by his crippling wounds. To make matters worse, Hood had to depend much on Hardee, his only experienced corps commander. Hardee was uninspired at the best of times, but at this time he was in an extended sulk over having been passed over in favor of his junior, Hood, for command of the army. At Peachtree Creek he was more than usually slow in getting his troops into position. The result was an attack that was several hours late. The Army of the Cumberland was already united on the south bank of the creek, and much of it was entrenched. Where it was not, the Confederate attackers scored a few temporary local successes before being driven back by Union counterattacks. Where the defenders were already behind breastworks, the attack made no headway at all. When the firing stopped that evening, Confederate losses totaled 4,796 men, while Thomas’s casualties were scarcely more than one-third that many.

Sherman’s turning movement continued apace the next day, with the Army of the Tennessee gaining the railroad east of Atlanta and then pushing westward toward the city, driving the Confederate defenders before them. With the failure of his first offensive, Hood faced again the unpleasant choice of either attack or retreat, with the latter meaning the abandonment of Atlanta. Again Hood chose to fight. During the thirty-six hours after the fighting had stopped along Peachtree Creek, Hood hastily shifted his troops through the city from the north side to the east for a blow against McPherson. Doing the hardest marching was Hardee’s corps, which had been the most heavily engaged at Peachtree and now had the assignment of marching all the way around McPherson’s left (southern) flank to hit the Army of the Tennessee in the rear. Hood was trying to make war the way he had seen Lee and Jackson do it in the Army of Northern Virginia. His plan for the attack on McPherson was very similar to what Lee and Jackson had done to Hooker at the Battle of Chancellorsville. Hardee would attack the Federals in flank and rear while the rest of the army, save for light forces detailed to hold the lines in front of Thomas and Schofield, would attack the Army of the Tennessee in front.

Across the lines, Sherman believed Hood had gotten all the aggressiveness out of his system in the July 20 assault along Peachtree Creek and would shortly retreat and abandon Atlanta. The Union general’s chief concern now was the possibility that Lee in Virginia might send reinforcements to Hood. Grant had recently telegraphed to warn that in the deadlocked situation on the Petersburg front he could no longer guarantee that Lee could not do so, and everyone remembered Rosecrans’s painful discomfiture at Chickamauga the preceding fall, in large part due to the arrival of troops detached from the Army of Northern Virginia. To forestall the repetition of such an event, Sherman wanted the Georgia Railroad, the most likely avenue for the approach of troops from Virginia, thoroughly destroyed for many miles east of Atlanta. On the morning of July 22, he decided that the single cavalry division he had working on that task of destruction was not going to be enough, and he told McPherson that he wanted an entire corps of the Army of the Tennessee, the Sixteenth, assigned to the job.

McPherson thought otherwise. His skirmishers had advanced that morning and found that although the Confederates had pulled back from some of the more advanced positions on his front, they were still present in force, well dug in, and showing no signs of being ready to evacuate Atlanta. Furthermore, McPherson believed his old classmate Hood was going to attack again, soon, and against the Army of the Tennessee’s exposed left (southern) flank, where McPherson proposed to post the Sixteenth Corps. Sherman was unconvinced, but he liked and respected McPherson and so agreed to let him keep the Sixteenth Corps on his left flank until midday and then, if nothing happened, to dispatch it on the track-wrecking mission.

Midday came and no attack from Hood. McPherson with a number of his officers was sitting in the shade of a grove of trees. Some were finishing up lunch while McPherson prepared to write an order shifting the Sixteenth Corps from flank protection to railroad destruction. Just then firing broke out on the army’s flank and rear, exactly where McPherson had predicted. The rapid crescendo of the sound indicated a major assault, and McPherson hastily rode off to inspect his lines. The Sixteenth Corps was just where it needed to be, and it stopped the first onset of the Confederate flanking attack. Between the Sixteenth Corps and its neighboring unit to the right, the Seventeenth Corps, was a gap in the Union line, and as McPherson reconnoitered and issued orders to bring up reserves to plug it, Confederate attackers swarmed through the gap and fatally shot the Union general.

The action that would come to be called the Battle of Atlanta was the largest and most hotly contested of the several clashes around the city. Hardee’s flank march was a hard one for his battle-weary troops, and once again, this time with a better excuse, they were late in getting into position. That was the reason the attack had not come when McPherson had predicted. Now with its commander dead, the Army of the Tennessee felt the full weight of the Confederate attack, both in front and via the gap in its line, against its flank and rear.

Hood had indeed succeeded in doing something very much like what Lee and Jackson had done to Hooker at Chancellorsville, but Lee and Jackson had not been up against the Army of the Tennessee. Organized by Grant and seasoned by two years of hard but successful campaigning, the army refused to believe it could be beaten. Its new commander, in place of the fallen McPherson, was a striking contrast to the badly frightened Hooker of Chancellorsville. Major General John A. Logan, commander of the Fifteenth Corps, was an Illinois politician in uniform. Nicknamed “Black Jack” by his men because of his swarthy complexion, Logan combined adequate military acumen with an amazing ferocity and an even more amazing ability to infuse his own fighting spirit into the men he commanded.