This Great Struggle (52 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

The month of September also brought political developments that made McClellan’s chances for the presidency appear noticeably slimmer. John C. Freémont and others among his new Radical Democracy Party had been appalled by the Democratic Party platform with its promise to save slavery and tepid hopes of saving the Union. Freémont did not like Lincoln but knew he would like McClellan even less. In mid-September he arranged a deal with Lincoln. Lincoln dropped from his cabinet Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, whom the Radicals despised, and Freémont withdrew from the presidential race. With Freémont gone, Lincoln’s chances of reelection rose still higher.

The presidential election of 1864 was the first to occur while the nation was in the midst of a major war, and the very fact that it came off as scheduled and that the government allowed the people what amounted to a referendum on the conflict that had been raging for the past three and a half years was a major triumph for self-government and a testament to the resilience of what Lincoln had called “the Great Republic.” The fact that the election was taking place during wartime also meant that for the first time in the nation’s history a significant percentage of the eligible voters were in the army. Soldiers in the field had never before voted in U.S. elections, but for 1864 most of the northern states passed laws enabling them to do so. In Indiana the Democrats controlled the legislature and stubbornly refused to allow soldiers to vote anywhere except in their home counties. Lincoln hinted in a letter to Sherman, whose armies included most of the state’s regiments, that it would be helpful if he could furlough as many Indiana soldiers as possible without jeopardizing military operations. In the lull that followed the fall of Atlanta, Sherman, who fully sympathized with Lincoln’s desire not to see the Hoosier soldiers disenfranchised, furloughed them en masse.

Sherman also furloughed two of his best corps commanders. Both Frank Blair and John A. Logan had been politicians before the war, though neither was a political general in the purest sense of the term. Blair was the brother of fired Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, and Logan had been a Democrat before the war. Now both returned to their home states, Blair to Missouri and Logan to Illinois, to campaign for Lincoln.

When election day came, Lincoln garnered just over 2.2 million votes to McClellan’s 1.8 million. Lincoln’s 55 percent share of the popular vote borders on being a landslide. The wide distribution of his support throughout the loyal states turned that margin into a major electoral landslide, with Lincoln receiving 212 electoral votes to McClellan’s 21. The Democratic candidate captured his electoral votes in his home state of New Jersey, plus the border slave states of Delaware and Kentucky. Otherwise, Lincoln’s statewide margins of victory were under five percentage points only in New York, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut.

Notably, while 55 percent of the voters nationwide chose Lincoln, 78 percent of Union soldiers did so. As it turned out, their votes did not decide the election, as Lincoln would have won even without them. Yet it was significant in another way. Cynical historians write as if all wars are decided and directed by politicians who carefully keep themselves out of harm’s way while herding the unwilling masses to their deaths as cannon fodder, and there were those on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line during the Civil War who looked at the Union and Confederate draft laws and complained that the conflict was “a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” Yet the overwhelming majority of Union soldiers, men who by then knew firsthand what war meant and who would bear the burdens and losses of its continuance, announced with their votes that this was their war and their fight and that they believed the causes of Union and emancipation were worth pressing on to final victory, cost what it might.

A victory for McClellan in the election of 1864 might or might not have led to Confederate independence, but such an event was the Confederacy’s last realistic hope of survival beyond the meager few months that its dwindling armies might be able to keep some fragment of its claimed territory out from under the boots of blue-clad soldiers. Lincoln’s victory meant that Confederate defeat, with the attendant restoration of the Union and abolition of slavery (a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery throughout the entire United States had already passed the Senate and was pending consideration in the House), was as certain as nearly any future event could ever be in the course of human affairs. The Union was now committed to prosecuting the war more vigorously than ever, if need be until at least 1867 if not 1869, and the Confederacy could not hope to survive even to the earlier of those dates.

SHERMAN IN ATLANTA

All that remained now was to convince the people of the Confederacy that the end was at hand for their slaveholders’ republic and that they ought to give up and accept it. The question was how many more men would have to die or be maimed before that end arrived.

In Virginia, Grant’s and Lee’s armies continued to face each other from their trenches stretching from the north side of Richmond, down the east side of Richmond and Petersburg, and around to the south of Petersburg. Fighting flared every few weeks as Grant either reached farther west across the south side of Petersburg or jabbed at Lee’s lines either north or south of the James River to force the Confederate general to keep every sector of his line manned, thus hamstringing Lee’s efforts to match Grant’s repeated grabs for Petersburg’s one remaining southern rail connection, the Southside Railroad, southwest of town. Elements of the battle-weary Army of the Potomac turned in several strikingly poor performances in these operations, but with each passing month Grant weakened and stretched Lee’s army and fastened his own grip more tightly than ever on it and on Richmond and Petersburg.

In Georgia, once the euphoria of capturing Atlanta had worn off, Sherman experienced several weeks of frustration as he tried to hold what he had gained and figure out what to do next. His biggest problem was one that had plagued him all the way down from Chattanooga, and that was his reliance, for every hardtack cracker and piece of salt pork his men ate, on a single set of rails leading all the way back to Louisville. The problem was worse now not only because the distance was longer than it had been at any time during the campaign but also because, at least as it appeared initially, Sherman would have more mouths to feed. As was typical when a southern city fell under Union control, the Confederates left behind a population of thousands of noncombatants, including many families of Confederate soldiers, who were thus destitute. Rather than see them starve, Union officers in places such as Nashville, Memphis, and New Orleans had provided them regular rations. Thus, the northern taxpayer got to pay not only for the feeding and maintenance of the nation’s army but also for the feeding of a large number of the families of those bearing arms against the nation.

Sherman was determined that it would be different in Atlanta, and so on September 7 he ordered the evacuation of the remaining civilian population of the city either south into Rebel lines if they chose or else north to someplace where, if the government did have to feed them, it could at least do so more conveniently and without impinging the flow of supplies to its own armies. He offered the assistance of his troops and their supply wagons to transport the evacuees and their possessions. The mayor and city council protested the order, and Hood, on being informed by flag of truce to be ready to receive the refugees, wrote a letter condemning the action. Sherman was unmoved. To the mayor he wrote,

We must have

peace

, not only at Atlanta, but in all America. To secure this, we must stop the war that now desolates our once happy and favored country. To stop war, we must defeat the rebel armies which are arrayed against the laws and Constitution that all must respect and obey. To defeat those armies, we must prepare the way to reach them in their recesses, provided with the arms and instruments which enable us to accomplish our purpose.

1

That would mean that Atlanta would have to serve as a supply depot rather than a home for families, and the families might as well leave now, when they had a good opportunity of doing so. “You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will,” Sherman continued:

War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out. I know I had no hand in making this war, and I know I will make more sacrifices today than any of you to secure peace. But you cannot have peace and a division of our country. . . . You might as well appeal against the thunder-storm as against these terrible hardships of war. They are inevitable, and the only way the people of Atlanta can hope once more to live in peace and quiet at home, is to stop the war, which can only be done by admitting that it began in error and is perpetuated in pride. . . . I want peace, and believe it can only be reached through union and war, and I will ever conduct war with a view to perfect and early success. But, my dear sirs, when peace does come, you may call on me for any thing. Then will I share with you the last cracker, and watch with you to shield your homes and families against danger from every quarter.

The order stood, and Union troops helped the remaining citizens of Atlanta in moving their belongings out of town, either to the railroad for the trip north or to Confederate lines, whence they could continue their journey south.

In the weeks that followed, Hood chose not to attempt to defend the two-thirds of the state of Georgia Sherman had not yet taken but instead moved his army into northeastern Alabama. From there he advanced into North Georgia and attempted to cut Sherman’s railroad supply line somewhere north of Atlanta. Sherman left enough troops to hold the city and with the rest of his force marched north to counter Hood and protect the railroad.

For the next several weeks, Union and Confederate forces maneuvered around northwestern Georgia without coming to grips while both commanders grew increasingly frustrated. Hood’s men could tear up railroad tracks, but Sherman’s repair teams had them running again within hours. What Hood could not do was destroy a facility, such as a tunnel, that would not be easily repairable. Nor could he seize and hold a position astride the railroad. Always the approach of Sherman’s larger army compelled him to relinquish his grip on the railroad and beat a hasty retreat. Sherman, for his part, was confident that he could crush Hood’s army in battle, but Hood would not hold still long enough, and Sherman could not catch him. Meanwhile the armies were marching up and down the same swath of country over which they had campaigned earlier that year.

Despite his success in keeping Sherman occupied in North Georgia and preventing any further Union offensive movements deeper into the Confederacy, Hood was the first to lose patience and tire of the game. He decided to march his army back into Alabama, then turn north and cross the Tennessee River. From there he planned to invade Middle Tennessee and possibly go all the way to the Ohio River or beyond. He began the movement in late October.

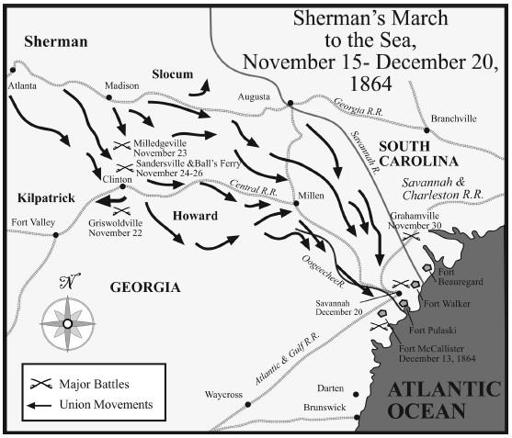

THE MARCH TO THE SEA

While Hood’s army marched west, Sherman was contemplating movement in a different direction. He had for several weeks been corresponding with Grant about what his own next step should be. Sherman’s proposal was to detach Thomas with two corps, plus the various Union garrisons in Tennessee, to deal with Hood while he, Sherman, took the remainder of his force, about sixty thousand men, on a march southeastward across nearly three hundred miles of Georgia to reach the sea at Savannah. Along the way, Sherman’s troops would destroy factories, railroads, and public buildings and requisition food and livestock. The effect would be not only to destroy the South’s logistical infrastructure but also to demoralize the white southerners in its path—as well as those who heard of it, including soldiers in the Confederate army far away in Virginia. “I can make this march,” Sherman wrote to Grant, “and make Georgia howl.”

In later generations, popular legend would have it that Sherman invented destructive warfare specially for use on this operation, and the claim would be taken up by some historians who ought to have known better. In fact, the practice of attacking an enemy’s economy and infrastructure and thereby also his morale was as old as warfare, nor had it gone into disuse during the supposedly limited wars of the eighteenth century, much less those of the Napoleonic era. Such wars were certainly not limited in that way. All that Sherman proposed to do in Georgia was well within the existing laws and customs of war and not all that different, at least qualitatively, from what Lee and his army had practiced in Pennsylvania the preceding summer.

What was new and bold about Sherman’s proposed operation was that it involved leaving an intact enemy army to his rear while marching his own army deep into the enemy’s territory without any lines of supply or communication at all and on a scale of distance that would have been equivalent to Lee taking his army not merely to Gettysburg but all the way to New York City. True, Sherman had the advantage in numbers over Hood, but in an operation of this type, the more men he had, the sooner he would run out of supplies if enemy action should force him to halt. His army could continue living off the land only as long as it kept moving. To the trained military minds of the day, the plan seemed like asking to have his army trapped and captured. Grant was hesitant, but eventually his confidence in his old friend and faithful lieutenant prevailed, and he gave Sherman permission to go ahead.