This Great Struggle (54 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

Hood’s troops deployed from column to line and swept forward, engulfing Wagner’s two ill-fated brigades. Hundreds of Wagner’s men surrendered, and the rest fled toward the main Union position, half a mile to the rear. The Confederates raced after them amid shouts of “Go into the works with them!” As the running mass of humanity neared the Union breastworks, the defenders held their fire rather than loose their volleys into the faces of their fleeing comrades. Yet the Confederates were only a few steps behind—in some cases almost among—Wagner’s panting fugitives, and they surged over the works and swept the defenders back in a sector immediately on either side of the point where the Columbia Pike entered the lines. Opdyke led his brigade forward to fill the breach and drive back the Rebel penetration. Other Union troops rallied to join him. Hand-to-hand fighting raged around the buildings of the Carter plantation just inside Union lines. The Federals drove the Confederates back to the line of the breastworks, and then the two sides slugged it out across the parapet much as Lee and Grant’s troops had done at the Bloody Angle of Spotsylvania though for a much shorter duration.

The fighting ceased after nightfall, and the Confederates who had been pinned down in front of the Union breastworks withdrew to a safer distance. In other sectors of the line the attack had made no headway at all, with the attackers being mowed down by the intense fire coming from the breastworks, where some of the defenders had repeating rifles. During the night, Schofield completed his withdrawal to the north bank of the Harpeth and continued his march to Nashville, leaving the town and battlefield to the Confederates, who took possession the next morning.

Hood’s soldiers and Franklin civilians alike then busied themselves tending the 3,800 wounded and burying the more than 1,700 dead Rebels lying on the battlefield. Members of the Carter family found Captain Theodric “Tod” Carter of the Twentieth Tennessee Regiment lying badly wounded in front of the breastworks and brought him to the house that had been his boyhood home and the center of the previous evening’s fiercest fighting. He died the next day, across the hall from the room in which he had been born, twenty-four years before.

In all, including missing and captured, Hood had lost more than 6,200 men. Among them were six generals killed or mortally wounded, seven more generals who would survive their wounds, and an additional general who was now on his way to Nashville as a prisoner of war—a loss of fourteen generals. Among the dead generals was Patrick R. Cleburne, widely believed, then and since, to be the best division commander in the Confederacy. In addition, Hood’s army lost fifty-five regimental commanders. The Army of Tennessee was a wreck. Schofield’s casualties, which had come mostly in Wagner’s division and around the Carter house and outbuildings, numbered little more than one-third that many.

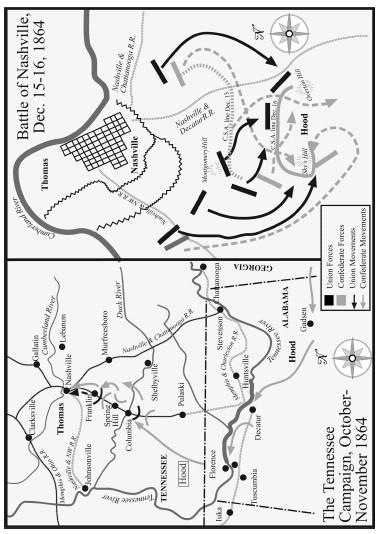

Since Schofield had left the battlefield in his hands, Hood claimed Franklin as a victory, though if Hood could have restrained his aggressiveness and perhaps his rage, Schofield would have been more than happy to have left Franklin and its environs to him without any battle at all. With little else to do in the wake of his Pyrrhic victory, Hood pursued Schofield to Nashville and encamped his army south of the town as if he could hope to besiege it with the thirty thousand or so men he still had left in the Army of Tennessee. Inside the extensive defenses of what was by then the most heavily fortified city on the continent other than Washington, D.C., Thomas by this time had some fifty-five thousand men. While Hood waited like Dickens’s Mr. Micawber for something to turn up, Thomas spent the next two weeks getting his army ready to take the offensive.

As day stretched into day of the odd standoff at Nashville, back in Virginia Grant grew concerned. He could see clearly that Hood’s best move was not sitting in front of Nashville, where he could accomplish nothing but rather slipping past Thomas and setting off on a raid that might penetrate all the way to the Ohio River. Such a raid would be a desperate endeavor, but in the Confederacy’s current state, as Grant’s clear military insight perceived, no lesser effort made any sense for the Rebels. Though extremely unlikely to change the outcome of the war, such a raid could make a world of trouble for Grant, who feared that Hood might see as much and that any day Thomas might find his large army facing empty Confederate breastworks while Hood’s army marched north bent on mischief. Grant sent Thomas one prodding message after another, each more pointed than the last, but nothing could budge the general whose army nickname was “Old Slow Trot.”

On December 8 a heavy ice storm swept through Middle Tennessee, virtually paralyzing movement on roads or cross-country and ruling out an attack. Back in Virginia, Grant’s impatience continued to mount. For him, the ice storm was just one more item in Thomas’s long litany of reasons why he could not act promptly, and Grant had heard that song from Thomas before. On December 13 Grant decided he had waited long enough. John Logan, commander of the Fifteenth Corps in the Army of the Tennessee, happened to be on leave in Washington at the time, and Grant dispatched him to Nashville with orders to relieve Thomas and take command in Nashville unless Thomas had launched an attack by the time he arrived. Logan had no sooner started on his journey than Grant decided that nothing but his own presence would suffice and prepared to set out for Nashville himself.

In the end, neither man made the trip. Grant had not started and Logan had not gone far when word arrived that Thomas had finally launched his long-awaited attack against Hood. On Thomas’s orders, two divisions of the U.S. Colored Troops, whose enlisted ranks were composed entirely of former slaves, advanced before dawn on December 15 and opened the battle with a diversionary attack on the Confederate right. Thomas’s main attack struck the Confederate left and drove it back throughout the afternoon. The early end of a mid-December day gave Hood respite to regroup his army on higher ground about two miles to the rear of the position he had tried to hold that day. He anchored his new line on Shy’s Hill on the left and Overton Hill on the right. It was a more compact position than the previous one, which was a necessity for his by now badly depleted army.

Thomas renewed the assault the next day. His troops spent the morning hours moving up to confront Hood’s new position. Then the attack once again opened against the Confederate left, followed by an even stronger Union assault against the right on Shy’s Hill. After several hours of fighting, the Confederate lines crumbled on Shy’s Hill, and then Hood’s entire army collapsed. What had been a battle became a footrace, as individual Confederate soldiers sought to escape the pursuing Federals.

Once again early nightfall came to Hood’s rescue, along with the onset of a steady rain. The Army of Tennessee regrouped again, this time to begin its long, weary trek out of its namesake state. In the days that followed, Union forces did their best to harass the retreat, which was ably screened by Forrest’s cavalry and the ongoing spell of cold, rainy weather. The Battle of Nashville cost Thomas a total of about three thousand casualties and Hood twice that many. Three-quarters of the soldiers Hood lost at Nashville were missing or captured. Continuing his retreat through northern Alabama, Hood on Christmas Day crossed back to the south bank of the Tennessee River with roughly half of the thirty-six thousand men he had taken with him bound north little more than a month before. Three weeks later Hood formally asked to be relieved of command, and Davis promptly complied.

THE FALL OF FORT FISHER AND THE LAST BID FOR A NEGOTIATED PEACE

In the wake of Hood’s crushing defeat in Tennessee and Sherman’s capture of Savannah as the culmination of his March to the Sea, heavy blows rained down on the nearly prostrate Confederacy, and it hardly seemed to matter if one of them failed to land squarely. In that same month of December 1864, Union forces attempted to take Fort Fisher, a powerful Confederate bastion guarding the approaches to Wilmington, North Carolina, the last major southern port open to blockade-runners. Because the operation lay technically within Ben Butler’s department, Grant had to allow that dismal political general to direct it, and the predictable result was failure. On December 27, Butler’s troops reembarked on the powerful fleet of transports and warships that had brought them and returned to their bases.

Disgusted with Butler’s performance and convinced that the political situation had now progressed to the point that this particular ambitious politician in uniform was no longer needed, Grant sacked Butler and ordered a new expedition against Fort Fisher, to depart immediately, this time under the command of Major General Alfred H. Terry. Like Butler, the thirty-eight-year-old Terry had been a lawyer without military background before the war. Unlike Butler, he had not been a politician and had started the war not as a general but rather as colonel of a regiment he had recruited. Several battles and two promotions later, Terry was a competent commander. Once again Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter and the strength of the Navy’s North Atlantic Blockading Squadron would be on hand to support the assault with four monitors, the ironclad steam frigate USS

New Ironsides

, three of the fifty-gun steam frigates that had been the pride of the fleet when the war began, and more than fifty other warships.

Terry landed his troops on January 13. Two days later, under cover of the heaviest naval bombardment ever fired in American waters, the assault went in. A naval landing party composed of two thousand sailors and marines staged a direct assault across the beach against the fort’s eastern, or sea, face, distracting the defenders’ attention, while the nine thousand army troops launched the main attack against the fort’s northern face. They fought their way into the fort and then fought their way through its multiple three-walled bays as the Confederates bitterly defended every inch of the fort. The battle lasted eight hours, and the two top-ranking Confederate officers were incapacitated by wounds before the fort was finally securely in Union hands.

With Fort Fisher lost, so too was the port of Wilmington as a haven for blockade-runners. That meant a final end to foreign manufactured war supplies for the Confederacy, including British Enfield rifles and Whitworth cannon. It even exacerbated the already dismal food supply situation for Lee’s army, a strange development in view of the fact that the Confederacy was still full of food, as Sherman had just demonstrated and was about to demonstrate again. So wrecked was the Confederacy’s transportation system that it was sometimes easier to feed Lee’s troops by importing foreign food through Wilmington rather than moving abundant domestic produce up from points farther south. With Wilmington closed, Lee’s scarecrow soldiers would have to take in their belts another notch.

Despite the steady drumbeat of military disasters, Davis would not even consider any negotiated peace agreement that did not begin with a clear acceptance of Confederate independence. Given Davis’s known stubbornness, that fact was not really as surprising as the very fact that the opportunity for a negotiated peace still existed with the Confederacy nearing complete collapse. Indeed, Lincoln had not initially thought the prospect was worth the effort. As early as his December 1863 address to Congress on Reconstruction, in which he had spelled out his Ten Percent Plan, Lincoln had opined that nothing was to be gained by talks with Davis since “the insurgent leader,” as Lincoln carefully styled him, had made clear on many occasions that he believed it his duty to accept nothing less than independence. Talks with Davis or with his emissaries would therefore be pointless, and the only hope lay in persuading the southern people to make peace without Davis and his administration.

Near the end of 1864 the intervention of two unusual men changed that.

New York Tribune

editor Horace Greeley had noticed that a peace movement of sorts existed within the Confederacy. Weak, scattered, disorganized, and diverse in its motivations and proposals, the Confederate peace movement included such men as North Carolina newspaper editor William Holden and Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens. Like the peace movement in the North, these men generally claimed, perhaps disingenuously, that the chief national war aim, in this case, independence, could be achieved through an immediate cease-fire followed by negotiations. As war weariness grew and the Confederacy visibly tottered toward its ruin, the presence of such a peace movement became an increasing threat to Jefferson Davis and his determination to fight to the bitter end and beyond.

Greeley saw in this an opportunity and on December 15 suggested to Francis Preston Blair Sr., former adviser to the late President Andrew Jackson, that he should go to Davis with a half-baked proposal for the Union and the Confederacy to stop fighting each other and jointly turn on the French in Mexico. After they had whipped the forces of Napoleon III, concluding a formal peace agreement between North and South would presumably follow easily. Blair took the matter to Davis on January 12. The concept was the brightest glimmer for independence that the Confederate president had seen in some time, so he readily gave Blair a letter to Lincoln offering to appoint commissioners to a conference for the purpose of “securing peace to the two countries.”