This Great Struggle (53 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

On November 9 Sherman gave his army orders for the march, stating famously, “The army will forage liberally on the country during the march.” He went on to state, however, that such gathering of foodstuffs was to be carried out by regularly organized foraging parties under the command of officers and that they were not to enter private dwellings or abuse civilians. The decision to burn a house, mill, or cotton gin was not to be made below the level of corps commander, and generally such destruction was to be reserved for neighborhoods in which overt acts of hostility—such as the burning of bridges—took place. Sherman told his men they could seize livestock as needed but admonished them, as in all their takings, to target the wealthy, slaveholding class and spare the poor and middling farmers.

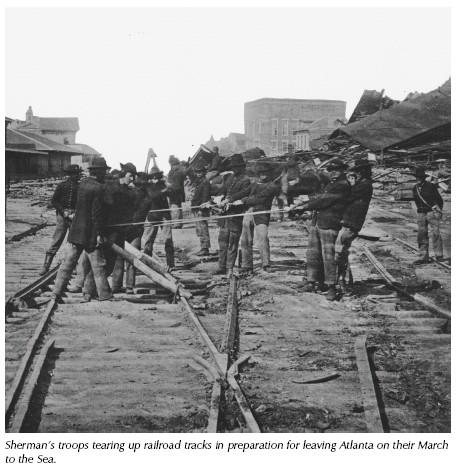

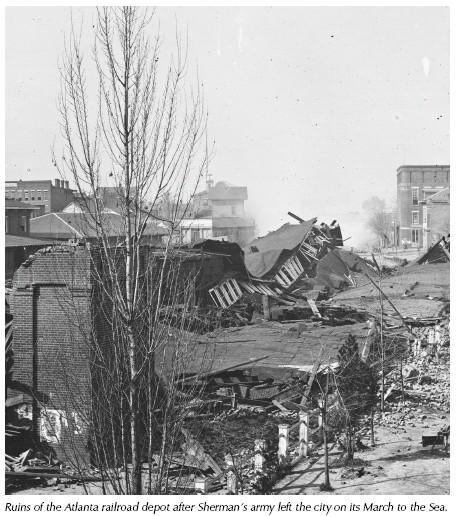

The march began on November 15. Sherman had his men cut the telegraph wires and burn the railroads behind them as well as any installations of military usefulness left in Atlanta. Sherman’s troops marched in two separate columns. As Sherman rode at the head of one of them that first day, he paused at the top of a rise and looked back at the smoke rising from Atlanta. He noticed that the troops marching past him were singing with one of the regimental bands the song “John Brown’s Body.” “John Brown’s body lies amouldering in the grave,” the lyrics repeated three times and then added, “His soul goes marching on.” The tune was the same as that of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and the chorus had the same words. Sherman later reflected that he had never heard the words sung “with more spirit, or in better harmony of time and place.”

For the most part, the troops obeyed Sherman’s orders. They foraged so efficiently that the army never had to halt to gather supplies but continued its march at an average of about ten miles per day. Food was abundant, and the men ate well, afterward fondly remembering the hams and sweet potatoes of Georgia. Railroads, depots, factories, and the like went up in flames, as did the plantation house and outbuildings of Confederate cabinet member Howell Cobb but relatively few other private homes. A few soldiers fell out of ranks and foraged individually without orders. The troops referred to such men as bummers but later appropriated that name for all who had marched with Sherman. As in Sheridan’s just concluded “Burning” in the Shenandoah Valley and all other Union operations in the South, peaceful civilians were safe from personal abuse or injury.

The march met little armed opposition. Hood had left his cavalry, under the command of Major General Joseph Wheeler, to harass Sherman, but Sherman’s own cavalry was more than sufficient to keep Wheeler’s horsemen well off the marching columns. Since the Confederate cavalrymen were also living off the land, the inhabitants of Georgia soon came to regard them as at least as bad a scourge as the passing Union army. Near Griswoldville, a division of Georgia militia composed mostly of middle-aged men and teenaged boys attacked a brigade of Sherman’s troops. Despite the militia’s almost four-to-one advantage in numbers, experience proved to be the decisive factor, as the battle-hardened Union veterans easily repulsed the attack.

Near the town of Millen, one of Sherman’s columns came upon one of the infamous Confederate prison pens where thousands of Union prisoners of war had been cooped up inside a stockade, open to the weather, with neither tents nor adequate food. The Confederates had evacuated the place, but the mass graves as well as the emaciated corpses the Rebels had not had time to bury told the story all too plainly. Angry Union soldiers burned the town of Millen in retaliation.

Slaves welcomed the advancing Federals with demonstrations of joy that even the crusty Sherman found touching. Sherman was a racist in the abstract and sometimes said or wrote ugly things on the subject, but when he encountered blacks face-to-face, their humanity touched his, and always he treated them kindly. In conversations all along the march, he urged blacks to remain at their homes and await the imminent end of the war to give them freedom. In this daring raid deep into enemy territory, his army did not have the wherewithal to feed, shelter, or transport them. They would be safer, he urged, if they stayed put for now. But it was no use. Former slaves flocked after the army in long columns that trailed behind each of Sherman’s corps, oblivious to prospects of food or shelter in their longing for freedom at the earliest possible moment.

Their presence led on at least one occasion to the sort of bad result that might be expected when masses of civilians followed an army deep in enemy territory. The march was nearing the coast when the Fourteenth Corps had to deploy its portable pontoon bridge to cross a broad stream known as Ebenezer Creek. Rumor had it that Confederate cavalry was shadowing the corps. If the corps commander left his pontoon bridge in place after the last of his soldiers got over, he ran the risk that the Confederates would capture or destroy it. That would trap his corps, which would then be unable to cross any of the remaining creeks and rivers that lay between it and the coast. No one could say how far the straggling column of fleeing slaves stretched out behind his last soldier. So he gave the order to take up the bridge. Blacks who had by then reached the bank panicked at the prospect of being returned to their contented way of life on the plantations and threw themselves into the creek, where a number of them drowned.

On December 10 Sherman’s army reached the outskirts of Savannah, where Confederate Major General William J. Hardee held the fortifications with ten thousand men. On the thirteenth Sherman had one of his divisions storm outlying Fort McAllister. The assault lasted fifteen minutes, and when it was over the fort was in Union hands and the Ogeechee River open to the supply vessels and warships of the U.S. Navy, which had been cruising offshore awaiting Sherman’s arrival. With a regular supply line and his men once more eating regular army rations of hardtack, salt pork, and beans, Sherman could take his time and besiege Hardee. Not relishing the prospect, the Confederate commander on December 20 withdrew into South Carolina before Sherman could close off that escape route. Sherman sent a telegram to Lincoln: “I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty guns and plenty of ammunition, also about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton.”

HOOD’S TENNESSEE CAMPAIGN

While Sherman had marched through Georgia from Atlanta to the sea, Hood had proceeded with his preparations for a campaign into Tennessee. Logistical problems and poor planning delayed Hood’s crossing of the Tennessee River until the third week of November, by which time Sherman had already left Atlanta behind and was deep in Georgia. Hood’s army marched north from Florence, Alabama, on November 21. By that time Thomas, with his headquarters in Nashville, was well apprised of Hood’s whereabouts and apparent intentions and had dispatched Schofield, whom Sherman had also detached for the defense of Tennessee, with two corps and orders to delay Hood’s march. Schofield awaited Hood on the north bank of the Duck River near Columbia, Tennessee, squarely athwart the road to Nashville and about fifty miles south of the city.

Hood arrived on the south bank of the Duck at Columbia, and his troops skirmished with Schofield’s. Well screened by Confederate cavalry commanded by Nathan Bedford Forrest, Hood on November 29 moved two of his three corps around Schofield’s left and across the Duck east of Columbia. Before the Federal commander realized what was happening, most of Hood’s army was bearing down on his line of communication and retreat near the village of Spring Hill, eleven miles north of Columbia. Around 3:00 that afternoon Schofield started his army marching north, out of Hood’s trap, but the last of his units was not able to file out of the entrenchments along the Duck River until 10:00 that night.

Meanwhile, Hood’s lead elements reached Spring Hill late that afternoon and skirmished with light Union forces guarding Schofield’s line of communication. With their overwhelming advantage in numbers, the Confederates could easily have driven the Federals out of Spring Hill, capturing the town and thus cutting off Schofield’s retreat. They could even more easily have moved directly against the Columbia Pike just south of Spring Hill, seizing the road and accomplishing the same purpose. Instead they did neither. The officer corps of the Confederacy’s Army of Tennessee had never been characterized by mutual trust and cooperation but rather by backbiting, blame shifting, and a concern for protecting one’s own record regardless of the consequences for the army or its mission. The result outside Spring Hill during the late afternoon and evening of November 29, 1864, was confusion and cross-purposes. Some officers thought their objective was the Columbia Pike. Others thought it was the town of Spring Hill itself and insisted that the movement against the pike be diverted in that direction. In the end, after indecisive skirmishing, they halted as darkness fell, just short of both objectives.

Hood arrived in person shortly thereafter, having ridden strapped to the saddle (because of his missing leg) since shortly after 3:00 that morning. Exhausted, he ordered a staff officer to find the two corps commanders and tell them to cooperate. Then, at about 9:00, he went to bed. About 2:00 in the morning Hood was awakened with a report that Union troops could just be seen somewhere out in front moving northward through the darkness, but Hood ignored the report and went back to sleep. North of Spring Hill Confederate cavalry patrols encountered Union supply wagons moving north along the road, but escorting Union infantry drove the Rebel horsemen back.

The next morning, November 30, Hood awoke to learn that during the night Schofield’s entire army had marched up the Columbia Pike and through Spring Hill, passing along the front of the Confederate army within as little as a hundred yards of its outposts. Hood was, in the words of one of his officers, “as wrathy as a rattlesnake,” and in a meeting with his generals that morning denounced them and their men as cowards. He ordered an immediate pursuit, and his army marched north, its generals enraged and humiliated.

They found Schofield at bay with his back to the Harpeth River at the town of Franklin, thirteen miles north of Spring Hill and about twenty miles south of Nashville. The Union commander had found the Harpeth River bridges badly damaged and needed time to repair them before he could continue his retreat. During previous operations in the area, Union troops had already built a substantial line of breastworks around the south side of Franklin, so Schofield put his troops into them, and into additional entrenchments they hastily dug, with orders to hold until the engineers could repair the bridges and the supply wagons were rolling toward Nashville again. Throughout the day the engineers made steady progress, and some of the wagons crossed via a nearby ford. With the bridges finished more wagons rolled north. Schofield was optimistic that by 6:00 p.m. he could pull all his troops back out of the entrenchments and evacuate the town, continuing his withdrawal to Nashville.

Hood and his unhappy army began arriving in front of the Union breastworks around 1:00 that afternoon and took up a position on Winstead Hill, about two miles south of town. Despite the absence of nearly a third of his infantry and most of his artillery, which had not caught up after diverting Schofield’s attention on the south bank of the Duck during Hood’s turning maneuver the previous day, Hood ordered an immediate all-out assault on the entrenched Federals.

Several of his generals protested the obvious folly of this course of action, and Forrest in particular claimed that with his cavalry plus a single division of infantry he could easily turn this position as they had turned Schofield’s position at Columbia. Hood, still seething from the affair at Spring Hill, would hear none of it and grimly insisted on the massed frontal assault. The sun would set around 4:30 that afternoon, and its rays were already steeply slanting as the twenty thousand Confederates advanced across the open plain two miles wide with colors flying while their bands played “Dixie” and “The Bonnie Blue Flag.”

The assault should have had no chance of success at all. However, that afternoon the last Union division commander to bring his troops into the position, Brigadier General George D. Wagner, had mistaken his orders, possibly because, as some who were present later asserted, he was drunk, and had ordered his three brigades to take up a position straddling the Columbia Pike in the open field about half a mile in advance of the breastworks. Veteran brigade commander Colonel Emerson Opdyke had chosen simply to ignore his obviously addled division commander and had taken his brigade inside the breastworks, assuming a reserve position behind the point where the Columbia Pike entered the fortifications. Wagner’s other two brigade commanders had obeyed orders and deployed in the hopeless position he had assigned.