Tolstoy (36 page)

Authors: Rosamund Bartlett

For his more advanced young readers, Tolstoy wrote two of his finest works of fiction, 'God Sees the Truth But Waits' and 'Captive of the Caucasus', whose power lies precisely in their carefully wrought simplicity. From the beginning, Tolstoy had intended the artistic level of his

ABC

to be in no way inferior to that of

War and Peace,

and both stories exemplified in fact the devices and the language he declared he would now employ in his adult fiction, as he explained in a letter to Nikolay Strakhov.

68

Work on the final compilation began in earnest in September 1871, and Tolstoy inveigled not only Sonya, but her uncle Kostya and his niece Varya into helping him as copyists. He was as exacting with his tiny stories for children as he was with his adult fiction, as Sonya commented in a letter to her sister,

69

but finally in December 1871 the first of the four books was ready, and Tolstoy set off for Moscow to find a publisher. This proved difficult, partly because of all the old Church Slavonic in the manuscript, forcing Tolstoy to resort to signing a deal with his old publisher Theodor Ries. But once his

ABC

was finally in press he was clearly excited, and when he wrote to Alexandrine in St Petersburg in January 1872 he told her that ifjust two generations of all Russian children, from the Romanovs to rural peasants, learned to read with his

ABC,

and had their first contact with art through it, he could die a happy man.

70

He was convinced this was the work he would be remembered for,

71

and rated it higher than

War and Peace

.

72

There was now an intense period of work to finish the three remaining books of the

ABC.

Typically for Tolstoy, the printing process had begun while he was still writing and adding to his manuscript, but he was an inveterate risk-taker and gambler. At times even he had to admit he was overwhelmed by the dimensions of his task. It was enough work for 100 years, he wrote to Alexandrine again in April: 'You need to know Greek, Indian and Arabic literature for it, as well all the natural sciences, astronomy and physics, and the work on the language is terrible—everything has to be beautiful, concise, simple, and most important of all, clear.'

73

Meanwhile, he was dying to try his

ABC

out, so in January 1872 he reopened the Yasnaya Polyana school to thirty-five local peasant children.

The school was located in the family house this time—in the front hall and in the rooms on the ground floor. Tolstoy taught the older boys in his study, while Sonya had a group of about ten pupils, mostly girls, whom she taught in another room. In the mornings they taught their own children, and after lunch they all pitched in to help teach at the school, including eight-year-old Sergey and seven-year-old Tanya, who were given the task of teaching the alphabet in the hall to the youngest pupils.

74

Five-year-old Ilya started out as a teacher too, but he proved to be far too strict with his pupils. His contract was terminated after he ended up fighting with his charges too often.

75

As an adult, Ilya could still remember the intense smell of sheepskin that the village children brought with them into the house, and the delightful anarchy that reigned in the schoolroom. Tolstoy allowed the children to sit where they wanted, get up when they wanted and answer questions all together—it was certainly a long way from regimented learning by rote.

76

The school broke up for the summer months, but teaching was not resumed in the autumn: Tolstoy had moved on to new pastures.

Tolstoy itched to see his

ABC

in print once he had handed over the manuscript, and eventually he lost patience with his publisher, who was proceeding at a snail's pace. The American primers Eugene Schuyler procured for him had given him the idea of using large typefaces and a particular design in the earlier pages of his

ABC

in order to make it easier for children to learn pronunciation, but this presented the typographers with a headache, as they were simply not used to printing anything other than with standard typefaces.

77

In May 1872 Tolstoy managed to transfer publication to Petersburg, having persuaded his friend Strakhov to oversee operations.

78

Strakhov, who had made his first visit to Yasnaya Polyana the previous summer, had already helped by producing modern translations of the old Slavonic texts, and now Tolstoy asked him also to grade the stories in the reading primer according to whether he liked them or not.

79

The 758 pages of the

ABC

finally appeared in November 1872, but its initial print run of 3,600 copies also proved to be its last. The next time the book appeared again in this format was in 1957, when a facsimile edition constituted volume twenty-two of the 'Jubilee' edition of Tolstoy's

Complete Collected Works.

Despite the high price of fifty kopecks for each constituent part of the

ABC,

Tolstoy had high expectations for its success and began thinking about the second edition even before it had been published.

80

He was to be bitterly disappointed. First of all, the book did not receive official approval for use in schools, despite Tolstoy sending a letter explaining its virtues to his distant relative Count Dmitry Tolstoy, the Russian Minister of Education.

81

Secondly, Tolstoy's desire to make some money from the publication got the better of him. He offered booksellers a twenty per cent discount, but insisted they paid in cash up-front, and so lost both their goodwill and valuable marketing potential. Sonya's younger brother Pyotr Bers, who lived in Petersburg, had been put in charge of sales, and he took a dim view of Tolstoy's attempt to break the power of booksellers in controlling distribution. His flat doubled up as a warehouse, and so he ended up being left with hundreds of unsold copies. The almost uniformly negative reviews which started appearing also did nothing to help sales of the

ABC.

Some critics objected to the dull grey paper it was printed on and the paucity of illustrations (twenty-eight), while others complained about the lack of any kind of introduction to explain for whom the book was intended.

82

They were all suspicious of Tolstoy's newfangled methods.

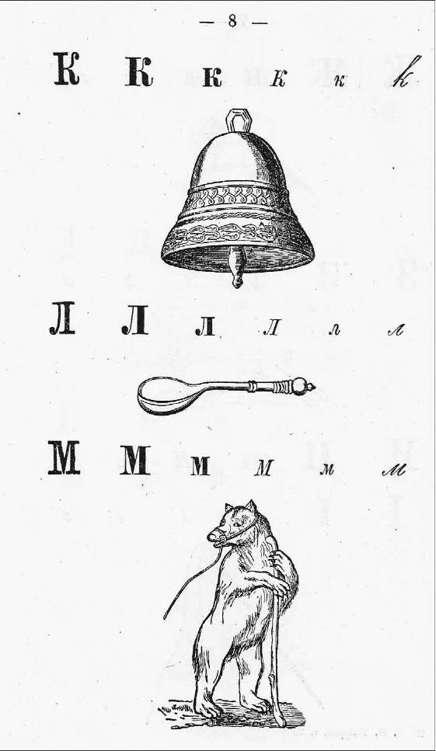

3. Page eight from the 1872 edition of Tolstoy's

ABC

book, showing the letters 'K for

kolokol

(bell), T for

lozhka

(spoon) and'm for

medved

(bear).

A writer as thin-skinned as Tolstoy could not fail to be stung by the criticism, but his belief in the

ABC

never wavered. Once he had published an open letter to the

Moscow Gazette

in June 1873 setting out what he regarded as the shortcomings of the teaching methods then in use, he calmed down. First, he decided to unbind the 1,500 unsold copies of his

ABC

and repackage them as twelve individual small volumes—they went on sale for between ten and twenty-five kopecks each.

83

Then a dozen young teachers from rural schools in the area came to spend a week at Yasnaya Polyana in October to study his methods.

84

In January 1874 Tolstoy was given the opportunity to defend his approach to the Moscow Literacy Committee, which accepted his proposal to conduct an experiment comparing his teaching methods with those that had been officially adopted. When the results of this experiment were inconclusive, he published a fifty-page

profession de foi

about his teaching methods in the august and widely read journal

Notes of the Fatherland

which finally provoked wide public debate.

85

'On Popular Education' is Tolstoy's heartfelt pedagogical manifesto.

Tolstoy goes into extraordinary detail in his discussion of pedagogical methods in 'On Popular Education', and shows deep knowledge of the educational provision in his own district. He summarised the flaws of Russian primary education as: '(1) lack of knowledge of the people, (2) the attraction of teaching what the pupils already know, (3) a tendency to borrow from the Germans, and (4) a criticism of the old without the establishment of new principles.'

86

Tolstoy had strong ideas about how Russian children should be taught letter and syllable formation, and was adamant that the phonetic method that had been adopted from Germany was not practicable in Russia, and certainly not suitable for disadvantaged peasant children. In some respects, he was ahead of his time, as what he was advocating later became axiomatic in twentieth-century remedial education.

87

Tolstoy's

ABC

was eventually approved by the Russian government in September 1874. Even repackaged, it had continued to sell poorly, and Tolstoy complained that he made a loss of 2,000 roubles,

88

but he was now keen to revise it.

To begin with, Tolstoy's plans for revision were minor, but typically for him, he ended up producing an almost completely new book. Something similar had happened with

War and Peace,

which he revised in 1873 for a new, third edition. His new frame of mind led him to turn six volumes into four, translate all the French text in the novel into Russian and place all his historical digressions into a separate epilogue. Strakhov was also instrumental in this project. For his

New ABC,

as it was now called, Tolstoy actually heeded his critics by providing an introduction and reducing the cost.

89

He wrote more than 100 new miniature stories, but by separating the 'ABC' section from the reading primer, he reduced the overall size of the book to ninety-two pages. It went on sale for a much more reasonable fourteen kopecks.

90

The

New ABC

proved to be as successful as the first edition had been a failure. It was published in February 1875, was swiftly recommended by the Ministry of Education, and became a best-seller, running into twenty-eight editions during Tolstoy's lifetime, with print runs of up to 100,000. Over a million copies had been sold by the time of his death. No other textbook was more widely read in pre-revolutionary Russia.

91

The poet Anna Akhmatova was just one of scores of Russians who benefited from Tolstoy's child-centred approach in learning their alphabet. The new primer, now entitled

Russian Books for Reading,

was based on the texts used in the first edition and was published later in October 1875. Since most of the first book from the 1872 edition had gone into the

New ABC,

Tolstoy produced twelve new stories and fables for the first of the four parts.

92

They proved equally popular with Russian children.

Tolstoy had conclusively proved that he wanted to improve the deplorable literacy levels in Russia, and that he cared deeply about Russian boys and girls of all classes discovering the joys of their native language when they learned to read. But what about his own children? What kind of a teacher was he to them? What was it like being used as a guinea-pig for his educational ideas? What was it like, indeed, growing up with a famous writer for a father? In October 1872 Tolstoy responded to Alexandrine's request that he for once tell her something about his children—for the most part, his letters to her, as to everyone else, concerned his current projects and intellectual preoccupations. It was indeed rare for Tolstoy to talk much about his family in his letters, and the thumbnail sketches he provides of his six children are thus often quoted.

Tolstoy described fair-haired Sergey, his eldest, as being bright, with a natural ability for mathematics and art. He was a good pupil, he told Alexandrine, and proficient in gymnastics, but rather gauche and absent-minded. Tolstoy was flattered to think Sergey reminded some people of his brother Nikolay, who had been famous for his lack of ego. Unlike Sergey, sensitive, pink-cheeked Ilya was always healthy, Tolstoy wrote, but he did not like studying much. Also unlike Sergey, he was a great original, and rather pugnacious, but at the same time he had a great capacity for tenderness, and had an infectious laugh. Tolstoy was confident that Sergey would excel in any environment, but he felt that Ilya would always need the strong leadership of someone he respected. Eight-year-old Tanya was very like her mother, Tolstoy wrote, and was already very maternal, liking nothing better than to take care of her younger siblings. Lev junior, then three and a half, he described as lithe, graceful and very capable, but for sickly little Masha, whom he described as 'very clever and unattractive', he foresaw a life of seeking and not finding. 'Skin white as milk, blonde curly hair; strange, large blue eyes—strange because of their deep, serious expression'—Tolstoy felt she would be a mystery to everyone. He openly confessed to Alexandrine that he found children in general hard to deal with until they were about three years old, but described Pyotr, the youngest, as a wonderful, bouncing six-month- old baby.

93