Tolstoy (40 page)

Authors: Rosamund Bartlett

Another immediate stimulus for

Anna Karenina

came from France. In March 1873 Tolstoy wrote to his sister-in-law Tanya to ask if she had read

L'Homme-femme,

an essay by Alexandre Dumas fils which had created a storm in Paris the previous year and had already been reprinted several dozen times.

17

Dumas wrote his essay as a reaction to coverage in the French press of the trial of a man who had murdered his 'unfaithful' wife, from whom he had separated. Specifically he was responding to an article which deplored the French laws which virtually condoned such crimes (the man was sentenced to a mere five years), and proposed divorce as the solution. This could never have been an option in this case. After a brief period following the French Revolution when France had the most liberal divorce laws in the world, divorce had been made illegal there in 1816 and would remain so until 1884.

18

For Dumas, marriage was a bitter, irreconcilable struggle between the sexes in which the woman prevails, but he argued that in this case the husband was ultimately the moral arbiter, and so had the right to kill an unfaithful wife who continued to be recalcitrant. Tolstoy was deeply impressed with Dumas's analysis of marriage. As well as introducing a discussion of his essay in one of the early drafts of

Anna Karenina,

19

he would take issue with many of its fundamental points in his account of Levin and Kitty's marriage. He would also engage, of course, with the entire tradition of the French novel of adultery that had been created by authors such as Flaubert, Zola and Dumas.

20

Dumas's own life, meanwhile, or rather that of his wife, provides interesting commentary on the themes of

Anna Karenina,

for he was married to Nadezhda Naryshkina, a Russian aristocrat who had committed adultery and borne an illegitimate child. Naryshkina had also been involved in an infamous murder case in Moscow in 1850 which shocked and thrilled Russian polite society, Tolstoy included. She was a captivating woman who had been married at a young age to Alexander Naryshkin, a scion of one of Russia's most distinguished aristocratic families. After bearing him a daughter, she resumed her career as one of the grandes dames of Moscow high society, and was renowned for arriving last at soirées, preferably no earlier than midnight. Tolstoy, who was her contemporary, was also living in Moscow at this time, and he described her as 'très à la mode' in a letter to Aunt Toinette. In 1850, when she was twenty-five, she began an affair with a Vronsky type—a handsome, wealthy aristocrat called Alexander Sukhovo-Kobylin, who was a talented dramatist and had the reputation of being a Don Juan. Naryshkina then became caught up and later implicated in the murder of his French mistress, a crime for which Sukhovo-Kobylin was (probably wrongly) arrested and imprisoned, along with two serfs who were convicted and sent to Siberia. Pregnant with her lover's child, the flame-haired femme fatale hastily decamped with her daughter to Paris, where she immediately made a name for herself in the city's top salons. It was in Paris that she met Dumas, the illegitimate son of Dumas

père,

who had come to fame after the publication of his 1848 novel

La Dame aux camélias,

inspired by his relationship with a celebrated Parisian courtesan (and later turned into Verdi's opera

La Traviata).

Naryshkina's husband refused to give her a divorce, also threatening to take their daughter away from her, and she was able to marry Dumas only after Naryshkin's death in 1864.

Tolstoy wrote to tell Toinette about the scandalous murder case which was a subject of Moscow gossip for many years,

21

and he may well also have heard about Naryshkina's high-profile relationship with Dumas during his later visits to Paris. Dumas's reflections on marriage in

L'Homme-femme

were clearly the product of his experience as husband to Nadezhda Naryshkina, with whom he had two daughters, and they struck a chord with Tolstoy. It was Aunt Toinette, however, who had perhaps the greatest influence on Tolstoy's views about adultery. In his memoirs, in which he writes about her at length, Tolstoy records telling her late one night about an acquaintance of his, whose wife had been unfaithful and absconded. When he expressed the view that his friend was probably glad to be rid of his wife, he describes how Toinette at once assumed a serious expression and urged instead forgiveness and compassion.

22

This is precisely the sentiment Tolstoy voices through his unsung heroine Dolly in

Anna Karenina.

When Karenin tells Dolly about his predicament at the end of Oblonsky's dinner party in Part Four of the novel, she pleads with him not to bring shame and disrepute on his wife by divorcing her, as it would destroy her. Toinette's general view, that one should hate the crime, but not the person, was essentially Tolstoy's, and holds the key to why Anna Karenina is one of the most compelling and complex literary characters ever created.

The story of how Tolstoy actually came to begin

Anna Karenina

has gone down in the annals of Russian literary history, and involves Sonya, Toinette and his eldest son. Sergey, then nine years old, had been badgering his mother to give him something to read aloud to Toinette, who was by then old and frail and in need of diversion. Sonya recorded in her diary on 19 March 1873 that she had given Sergey the fifth volume of the family's edition of Pushkin, which contained his

Tales of Belkin.

Aunt Toinette apparently soon nodded off, and Sergey also lost interest in Pushkin's immortal prose, but Sonya was too lazy that day to take the book back to the library, and so left it upstairs on the windowsill in the drawing room. Tolstoy naturally picked it up, and a few days later he wrote excitedly to Strakhov to tell him he had been unable to put it down, even though he was reading the

Tales of Belkin

for about the seventh time. The volume also contained some unfinished sketches for novels and stories, including one fragment beginning 'The guests arrived at the dacha' which particularly caught Tolstoy's eye. He was riveted by how Pushkin got straight down to the action, without even bothering to set the scene first or describe the characters. After the thirty-three false starts with Peter the Great, this was a revelation for Tolstoy, and it showed him how he himself should proceed in his own fiction. (Oddly, he seemed to have forgotten that he had more or less used precisely this technique with

War and Peace,

which also begins at a high-society soirée.) 'I automatically and unexpectedly thought up characters and events, not knowing myself why, or what would come next, and carried on...,' Tolstoy wrote unguardedly in the letter he drafted to Strakhov, which he later thought better about sending.

23

The idea of writing about the consequences of a woman's infidelity was there from the start,

24

but it would be a long time before his novel was called

Anna Karenina,

and began with that famous opening line:

All happy families are alike, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

Everything was confusion at the Oblonskys' house. The wife had found out about the husband's liaison with the French governess previously living in their house, and had told her husband she could not live under the same roof as him...

The narrator of Pushkin's fragment, which dates from the end of the 1820s, goes on to describe a drawing room filling with guests who have just attended a performance of a new Italian opera. The ladies take up position on the sofas, surrounded by gentlemen, while games of whist are started at tables nearby. Tolstoy also started the first draft of his as yet unnamed new novel with a scene in an aristocratic drawing room:

The hostess had just managed to take off her sable fur coat in the hall and give instructions to the butler about tea for the guests in the large drawing room, when there was the rattle of another carriage at the front door...

25

As in Pushkin's fragment, the guests in Tolstoy's new novel have all j'ust been to the opera—a performance of

Don Giovanni,

a work all about seduction and adultery. Their conversation focuses on the senior civil servant Mikhail Mikhailovich Stavrovich (the future Karenin) and his wife Tatyana Sergeyevna (the future Anna): she has been unfaithful, and he seems ignorant of the fact. The couple then arrive in person, followed later on by Ivan Balashov (the future Vronsky), who proceeds to have an intimate and animated conversation with Tatyana, scandalising those present. Stavrovich now realises the misfortune that has befallen him, and his wife is henceforth no longer invited to society events. It is a scene slightly reminiscent of the soirée at Princess Betsy's in Part Two of

Anna Karenina.

In his first draft Tolstoy sketched out eleven further chapters. Tatyana (Tanya) becomes pregnant and Balashov loses a horse race when his mare falls at the last fence. Stavrovich then leaves Tatyana and moves to Moscow; she gives birth and her husband agrees to a divorce. Tatyana's second marriage is no happier, however, and after Stavrovich informs her that their marriage can never truly be ended, and that everyone has suffered, she drowns herself in the Neva. Balashov goes off to join the Khiva campaign (Russian troops attacked the city and seized control of the Khanate of Khiva in 1873, just when Tolstoy was writing).

Tatyana has a brother in the first sketch (a prototype of Oblonsky), while her husband has a sister called Kitty, but there is no trace of Levin and his brothers yet, nor any member of the Shcherbatsky family. Stavrovich is portrayed sympathetically, while his wife is intriguingly both 'provocative' and 'meek'. Tolstoy had never before sketched a synopsis of a fictional work in advance, but in any case this raw material soon changed significantly. He developed and dramatically expanded every part of this storyline in future drafts except for his evocation of the state of mind of Balashov's horse during the race, which he subsequently decided to cut. Balashov's English groom is called Cord, as in the final version of the novel, but his mare is not Frou-Frou yet. To begin with she bears the English name of 'Tiny', and is referred to as 'Tani' (as the name becomes when transliterated) and also as 'Tanya', thus drawing an indelible link with his lover, which remains in the final version, although the association is not articulated.

Tolstoy was nowhere near ready to give any of this material to Sonya to copy out yet. Instead, he started a new draft of the beginning of his novel:

After the opera, the guests drove over to young Princess Vrasskaya's house. Having arrived home from the theatre, Princess Mika, as she was called in society, had so far only managed to take off her fur coat in the brightly lit hall in front of the mirror, which was festooned with flowers; with her small gloved hand she was still unhooking the lace which had caught on a hook of her fur coat...

26

This time he called his heroine Anastasia ('Nana') Arkadyevna Karenina, and replaced her yellow lace gown with the black velvet she will wear to the ball in the final version. Her husband is now firmly called Alexey Alexandrovich, but her lover's name has switched from Balashov to Gagin. Tolstoy ended up discarding this draft, but he would save up the detail of the caught lace for Anna to unhook in the final version of the novel, when she is leaving Princess Betsy's soirée after her fateful encounter with Vronsky.

Tolstoy wrote several more pages, but he was already beginning to chafe at the bit. He wanted to write a novel of adultery, but he did not want to be constrained by writing only about St Petersburg high society, even if his attitude towards it was sharply critical. With a few exceptions (Stavrovich, for example, has a conversation with a nihilist on a train), his social radius was thus far stiflingly small, and so he decided to introduce in his third draft the character of Kostya Neradov, a prototype of Levin. Neradov is a rural landowner, and both a friend of Gagin (the future Vronsky) and his rival for the hand of Kitty Shcherbatskaya, who also now makes her first appearance. The action, moreover, now moves to Moscow.

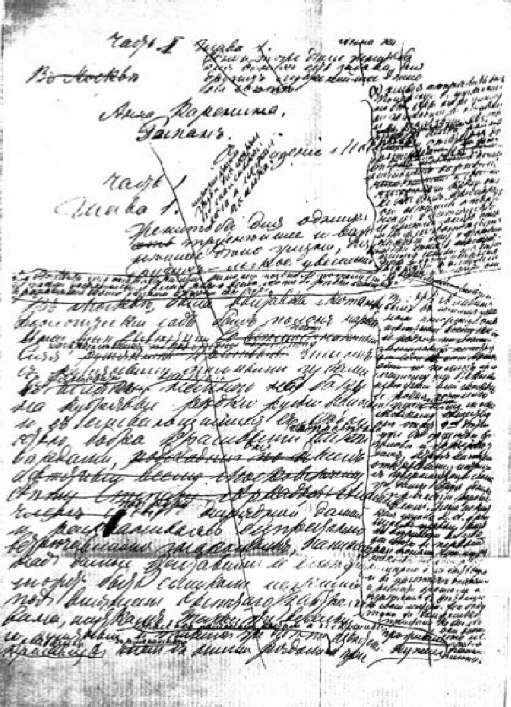

4. The fourth draft of the opening of

Anna Karenina,

1873

Tolstoy was gradually finding his way into his new novel. His fourth stab at an opening now received the title 'Anna Karenina', followed by 'Vengeance is Mine' as an epigraph. This draft begins with the familiar scene of a husband waking up after a row the night before with his wife, who has discovered his infidelity. 'Stepan Arkadyich Alabin' is almost Oblonsky. Anna comes to Moscow as peacemaker, and she meets Gagin at the ball. But still Tolstoy was not satisfied: there was no tension in the relationship between the Levin and Vronsky prototypes, as they were friends. He decided to change their names to Ordyntsev and Udashev, and now made them rivals for Kitty's hand rather than friends. It was time to try another beginning. Tolstoy took out a fresh sheet of paper and started a fifth opening draft: