Tolstoy (74 page)

Authors: Rosamund Bartlett

Since his illness in 1902, the situation at Yasnaya Polyana had been more or less peaceful. Tolstoy still hated having to live in the luxurious environment of his ancestral home. He still hated being served dinner by servants in white gloves, and he wanted to leave, but somehow he had stayed put. Despite his professed desire for a secluded life, there was little chance of that. Biryukov returned from exile in December 1904. He had been completing the first authorised biography of Tolstoy, and his subject now had the chance to read the manuscript and answer his questions before preparing it for publication.

159

The quiet Slovak doctor Dusan Makovicky also arrived in December 1904, and settled at Yasnaya Polyana as Tolstoy's personal physician. Makovicky's salary was paid by Chertkov, who now acquired a useful channel of communication about his friend's state of health, and much more besides.

160

A fervent Tolstoyan who had made his first visit to Yasnaya Polyana in 1894, Makovicky worshipped the ground Tolstoy walked on, and took to keeping a pencil and notebook in his trouser pocket so he could surreptitiously scribble down everything he said. The gathering of Tolstoy's utterances was a project Chertkov was also fanatic about. He had started it in 1889, and continued with it until 1923, when his appointed compiler died, by which time there were about 25,000 diverse and sometimes very trivial thoughts recorded in an enormous file.

161

With an eye to posterity, Sonya had meanwhile started writing what would prove to be an extremely long account of her own life as the spouse of an impossible genius. She also put together an inventory of the enormous library at Yasnaya Polyana, and started putting her husband's archive in order. In 1904 she was obliged to move everything from the Rumyantsev Library (where she had placed his manuscripts initially) to the History Museum next to Red Square, and so now on her trips to Moscow to take care of publishing business, she also spent her mornings copying out the material she needed.

162

Sonya was renowned for being short sighted (a photograph of her attending a photography lecture shows her sitting almost underneath the speaker), for lacking a sense of humour (a lot of Chekhov's early stories left her cold), and for being busy. Like her husband, she also never 'retired', and as well as becoming an accomplished photographer, she acquired skill in painting.

163

She also enjoyed being a grandmother. In 1905, after many miscarriages, Tanya gave birth to a daughter, also named Tatyana, who was affectionately given a 'matronymic' rather than the usual patronymic in deference to Tanya's heroic achievement in becoming a mother. 'Tatyana Tatyanovna' became the Tolstoys' fifteenth grandchild, and was particularly beloved.

The precarious harmony established after the Tolstoys returned home from the Crimea had disappeared by the end of 1906. A wonderful snapshot of life at Yasnaya Polyana just before everything began to disintegrate is provided by the Japanese writer Tokutomi Roka, who spent five days at the estate in June, and duly wrote an account of his visit. He arrived just before Sergey (now forty-three) married for the second time. Tokutomi had been Meiji Japan's most fervent Tolstoy devotee since the age of twenty-three, and having been brought up as a Protestant, was drawn as much to his religious philosophy as he was to his fiction. He took life just as seriously as Tolstoy, with whom he conversed in English. Apart from his hero, who was just as he expected, but 'looked all of his seventy-eight years', Tokutomi met most of the family: Sonya ('the look in her eyes was a little lacking in charm'), Masha ('sickly and thin'), her husband Nikolay ('gentle of voice and manner and typifies the effeminate Slavic male'), the 'fun-loving student' Sasha ('and her weight would be about 170 pounds'), as well as Lev and his Swedish wife Dora, plus Andrey, now estranged from his first wife, and Misha. Amongst the Tolstoy children, it was Sasha whom Tokutomi got to know best, and whom he obviously found a little overwhelming. He once encountered her 'zooming up on her bicycle, travelling like a cyclone' ('and with her physique I was sure she was certain to smash the machine'). Tokutomi also took care to describe the family's four dogs who were a presence at the outside dining table under the maple tree: a white Siberian, a brown pointer, a black setter and a black and white spaniel.

Tokutomi was accompanied on swims and walks by Tolstoy, and he noticed that he never forgot to attach the chain of his silver watch to his belt, and take with him a notebook with pencil thrust in it. During one walk in the woods, Tolstoy shared his thoughts on Russian writers such as Turgenev, whose works he described as 'remarkably beautiful, but not very deep'. Gorky, on the other hand, he declared had 'genius but no learning', while Merezhkovsky had 'learning and no genius, and Chekhov has a great genius, a great genius'. Towards the end of a sometimes rather awestruck account of his pilgrimage to Yasnaya Polyana, Tokutomi describes being taken to Tolstoy's study, and watching him breathe heavily as he wrote letters of reference for him with his goose-quill pen, his thick brows arched together: 'He is a prophet in his final years, his frame weakening day by day, but within him a raging fire burns ever brighter. Just to see him inspires you with a feeling of awe and makes you weep bitterly.' Tokutomi touches here on Tolstoy's extraordinary charisma, which affected even those immune to his religious message. Many were the sceptical Anglo-Saxon visitors to Yasnaya Polyana who found themselves in awe of Tolstoy's physical presence, and surprised by his deep sincerity. After replacing the quill in the rack, Tolstoy picked up a lamp to show Tokutomi the pictures on the wall of Henry George, his brother Sergey, William Lloyd Garrison, Syutayev, and a reproduction of Raphael's

Sistine Madonna,

divided into five panels, which had been given to him by his sister Maria.

164

Before they parted, Tolstoy showed Tokutomi his beloved

Circle of Reading

- an immense compendium of the thoughts of wise people he had compiled for every day of the year taken from an equally huge array of sources, including his own works.

The problems at Yasnaya Polyana began shortly after Tokutomi's departure. First Andrey and Lev told their father in no uncertain terms that they approved of capital punishment, which led to a dreadful row, with much slamming of doors. Tolstoy was upset for two days, and then became worked up again a few weeks later when Sonya insisted on taking to court the peasants who had chopped down some oak trees in their forest. Once again, Tolstoy threatened to leave home.

165

Then in August, having just turned sixty-two, Sonya fell seriously ill and almost died. On 2 September, attended by at least four doctors, she underwent an operation to remove the fibroid which had caused her to contract peritonitis. Remarkably, her constitution was as strong as that of her husband, and she recovered, but thirty-five-year-old Masha was not so fortunate. After catching a chill that November, she died in her father's arms.

166

Of all his children, it had been Masha who had been closest to him, and her death was a terrible loss.

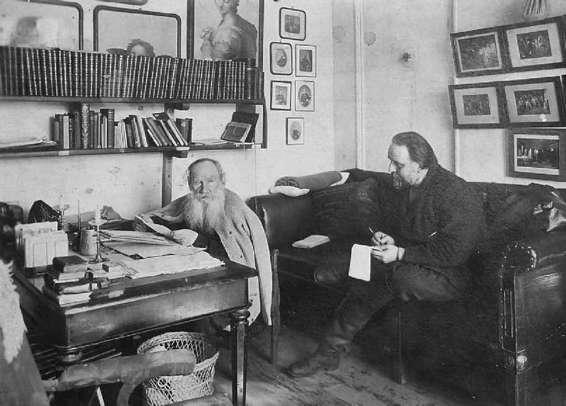

14. Tolstoy and Chertkov in his study at Yasnaya Polyana, 1907

Chertkov had spent several weeks near Yasnaya Polyana in the summer of 1906, and he returned with his family for the whole of the summer in 1907. This time Sonya was not as thrilled by the prospect as her husband was, and showed it. She caused further friction by insisting on employing guards for Yasnaya Polyana after some peasants had raided the vegetable garden one night and stolen some cabbages.

167

The armed Circassian hired to provide security proved to be very unpopular with the villagers, and Tolstoy was greatly pained. The autumn of 1907 was thus no happier than the autumn of 1906, and Sonya's estrangement from her husband increased still further when the businesslike Chertkov found an obliging twenty-five-year-old called Nikolay Gusev to become Tolstoy's secretary. Chertkov paid Gusev fifty roubles a month to help Tolstoy deal with his enormous correspondence, but for Sonya that meant another non-family member at Yasnaya Polyana who was privy to her husband's thoughts. Gusev arrived in September 1907, and took up residence in the upstairs room nicknamed the 'Remingtonnaya' for the Remington typewriter that had recently been installed there. A month later, he was arrested for spreading revolutionary propaganda, and spent two months in the Tula prison. The Russian government had resumed its previous tactics of targeting Tolstoy's followers, despite the fact it was Tolstoy himself authoring the anti-tsarist tracts.

168

Another source of depression for Tolstoy that autumn was his son Andrey's second marriage. Andrey's first marriage, to Olga Diterikhs, the sister of Chertkov's wife, had broken down soon after the birth of their two children, but to his father's horror, he had then taken up with the wife of the Tula governor. Ekaterina Artsimovich abandoned six children as well as her husband to pursue her passion with Andrey, and was six months pregnant with his child when they married in November. They had difficulty enough in finding a priest who was prepared to marry them when Andrey's divorce finally came through, and then they had to rush through the night to an obscure rural parish so the ceremony could be conducted at the crack of dawn, before the start of the forty-day Christmas fast.

169

Andrey, who had not seen much of his father when he was growing up, was a serial philanderer, and was soon unfaithful to his second wife.

The cause of the greatest happiness in Tolstoy's last years - the return of Chertkov - was also the cause of great unhappiness for his wife. Chertkov had worked indefatigably during his time in England. In 1900 he had moved from Essex to Christchurch in Hampshire (now Dorset), a pleasant town on the River Stour. His mother owned a plush residence at nearby Southbourne (where she would die, penniless, in 1922, at the age of ninety),

170

and she now bought her son a spacious three-storey detached house with a large garden, together with a building on Iford Lane for his printing press. The Purleigh colony had fallen apart, partly due to Chertkov's autocratic ways (he fell out with Kenworthy, Maude and Khilkov). A few Tolstoyans moved to the Cotswolds to set up a new colony at Whiteway (which uniquely survives to this day),

171

but the main centre for Tolstoyanism in Britain now became Tuckton House, Chertkov's residence in Christchurch. Russian-language publication continued under the Free Word Press imprint, but Chertkov now also set up the Free Age Press to publish English translations of Tolstoy's writings. In the first three years, before he fell out with his manager, Arthur Fifield (who had been secretary at the Brotherhood Church), the Press produced forty-three publications, with a combined print run of over 200,000.

172

Russian-language productivity was also impressive: in 1902 Chertkov started publishing the first Russian edition of

Tolstoy's Complete Collected Works Banned in Russia

under the imprint of the Free Word Press.

Chertkov also built a state-of-the-art, temperature-controlled vault to store all the manuscripts Tolstoy had been sending him, which now included his precious diaries. One of its custodians was Ludwig Perno, an exiled Estonian revolutionary who lived in nearby Boscombe, and he was made to promise that he would never leave the house without a guard.

173

Unlike so many other political exiles who were followed by swarms of spies, Chertkov led a life which was remarkably untrammelled by interference from the Russian government. He kept up an intense correspondence with Tolstoy during his years of exile, and was able to travel round England unhindered, giving lectures on Tolstoy and attending weekly 'Progress Meetings for the Consideration of the Problems of Life' in Bournemouth. He even played football for local teams in Christchurch.

174

Before Chertkov moved back to Russia in 1908 he coordinated the publication, both in Russia and abroad, of one of Tolstoy's most important and influential articles. 'I Cannot Be Silent' was written immediately after Tolstoy heard the news that twenty peasants had been hanged for attempted robbery and is one of his most finely articulated and heartfelt pleas for the government to end its systematic programme of organised violence, which he defined as worse than revolutionary terrorism. When the article was published in July, Tolstoy immediately received sixty letters of support - it was still a novelty for people in Russia to be able to read his broadsides. Many newspapers were fined for printing it, however. The liberal

Russian Gazette

had to pay a penalty of 3,000 roubles and the editor of a Sebastopol newspaper was arrested for pasting it up all over the city.

175

Thoughts of capital punishment now led Tolstoy back to the events of 1866, when he had failed to prevent Private Shabunin from being executed. In the late 1880s, a former cadet in the regiment who had witnessed the events had come to see Tolstoy. He wanted to discuss an account he had written and hoped to publish.

176

Tolstoy had refused, which seems only to have served to increase his feeling of guilt. In 1908 he finally resolved to speak out when questioned by Biryukov in connection with his biography. Bursting into tears three times while dictating an account of what had happened in 1866 to his secretary Gusev, Tolstoy now declared that Shabunin's execution had exerted far more influence on his life than all those events conventionally regarded as significant, such as bereavement, impoverishment, career setbacks and so forth. He confessed to being ashamed of his defence of Shabunin, which in retrospect he felt had been perfunctory and more concerned with legal details than with moral imperatives. It certainly stands in marked contrast to the impassioned stand taken in court by his fictional alter ego Nekhlyudov in

Resurrection,

which was conceivably written in part to assuage his guilt over the Shabunin affair.

177