Tolstoy (70 page)

Authors: Rosamund Bartlett

Assisted by Tolstoy's royalties, handsome contributions from wealthy Moscow merchants, unstinting donations from members of Kenworthy's colony at Purleigh (which brought it to near bankruptcy)

96

and English Quakers, over 7,500 Dukhobors made it to Canada on several specially chartered ships between December 1898 and May 1899. It was an enormous enterprise, involving Arthur St John, who travelled out to the Caucasus and was arrested and deported from Tiflis in February 1898, and Dmitry Khilkov, who had now completed his term of exile and took one group of Dukhobors initially to Cyprus, where conditions did not prove to be satisfactory. Then in March 1898, Chertkov happened to read an article by the exiled anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin, who was living in London but had just been to Canada in his capacity as a geographer to lecture on the glacial deposits in Finland.

In his article, Kropotkin wrote about the Mennonites who had left Russia in the 1870s to avoid conscription. They had settled in Canada, where they were now farming prairie land with considerable success. Chertkov invited Kropotkin to come to Purleigh to meet with him and the two Dukhobor representatives who had come to discuss their situation. After Kropotkin had convinced them that Canada was indeed the best place for the Dukhobors to settle, Aylmer Maude and Khilkov went on ahead to make arrangements (as a Tolstoyan, the seasick Maude was embarrassed at having to travel in a first-class cabin).

97

By October 1898 agreement had been reached with the Canadian authorities, and with the help of Kropotkin's friend James Mavor, a Scottish-born Professor of Political Economy at the University ofToronto and Pavel Biryukov in Geneva, who acted as intermediary in the communications between Russia and Canada, the

Lake Huron

was chartered to make the first of several month-long sailings between the port of Batumi on the Black Sea and Halifax, Nova Scotia. The future Bolshevik Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich accompanied one of the sailings. He had a deep interest in the oral tradition of Dukhobor hymns and psalms, and remained in Canada for a year in order to study their culture. Later, as secretary to Lenin, he would play a crucial role in protecting the Tolstoyans for a short while when they in turn became victims of persecution after the Bolshevik Revolution. Amongst the many other volunteers who also took part in the operation was Tolstoy's son Sergey who set off first for England in August 1898 to have discussions with Chertkov and the Quakers. During his stay in London, Sergey and the two Dukhobor representatives who had been visiting Chertkov were shown round the British Museum by Kropotkin. Wherever they went they were followed by a top-hatted Russian spy and curious glances aroused by the exotic clothes of the Dukhobors, who were dressed in traditional blue

beshmets

(the belted knee-length coats worn by the Caucasian Cossacks), baggy trousers and wool caps.

98

From London, Sergey went to Paris to help negotiate first French rights to

Resurrection,

and then in December he accompanied 2,140 Dukhobors on the first sailing to Canada.

99

Tolstoy was overjoyed by the rapprochement with his eldest son.

100

The exertion involved in writing and publishing

Resurrection

in serial form took a heavy toll on Tolstoy's health, and news that he had fallen ill spread rapidly throughout Russia. One person who was greatly concerned was Anton Chekhov, who a year earlier had gone to live in exile in the Crimea in a

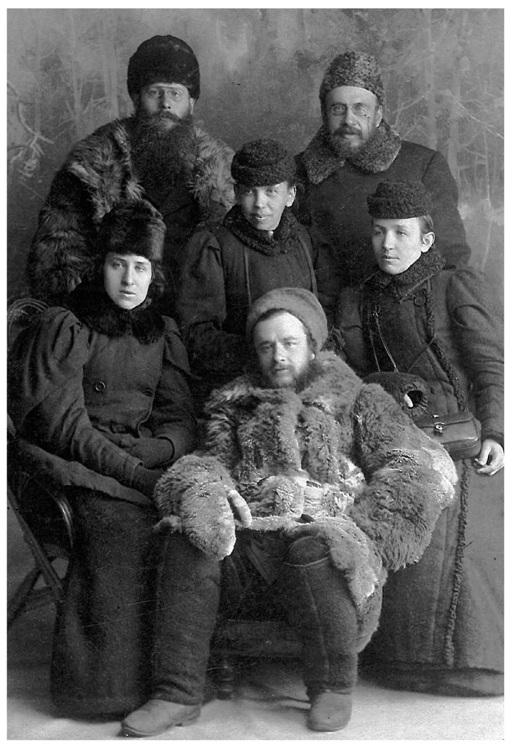

11. Dmitry Khilkov (left) and Sergey Lvovich Tolstoy (right) standing amongst a group of those accompanying the Dukhobors to Canada, 1899

desperate attempt to stem the rapid advance of tuberculosis. He had suffered his first serious haemorrhage in Moscow in March 1897, and been taken to a clinic near Tolstoy's house. After Tolstoy came to visit him and spent hours talking to him about immortality, he had suffered another haemorrhage.

101

Even though he was in faraway Yalta, Chekhov not only managed to procure a copy of

Resurrection

the minute it was published as a complete novel, but had already finished it by the end of January 1900, as he declared in a letter to the journalist Mikhail Menshikov: 'I read it straight through in one gulp, not in instalments or in fits and starts. It is a magnificent work of art.'

102

In this letter, Chekhov also confessed that Tolstoy's illness had alarmed him and kept him in a 'constant state of tension'. He went on to speak for no doubt millions of Russians when he explained why that was. It is a remarkable letter that deserves quoting at length:

I fear the death of Tolstoy. If he were to die, a large empty space would appear in my life. In the first place, there is no other person whom I love as I love him; I am not a religious person, but of all faiths I find his the closest to me and the most congenial. Secondly, when literature possesses a Tolstoy, it is easy and pleasant to be a writer; even when you know that you have achieved nothing yourself and are still achieving nothing, this is not as terrible as it might otherwise be because Tolstoy achieves for everyone. What he does serves to justify all the hopes and aspirations invested in literature. Thirdly, Tolstoy stands proud, his authority is colossal, and so long as he lives, bad taste in literature, all vulgarity, insolence and snivelling, all crude, embittered vainglory, will stay banished into outer darkness. He is the one person whose moral authority is sufficient in itself to maintain so-called literary fashions and movements on an acceptable level. Were it not for him the world of literature would be a flock of sheep without a shepherd, a stew in which it would be hard for us to find our way.

103

In fact, it was the much younger Chekhov who would die first.

It was just as Tolstoy fell ill in November 1899 that Orthodox hierarchs began to discuss seriously the question of what to do with the heretic in their midst. Some of the most scathing chapters in

Resurrection

had been directed at the Orthodox Church, and this was an acute problem for an institution whose prestige and moral authority were closely bound up with those of the Russian government, which felt threatened on several fronts by the end of the nineteenth century. The final instalment of

Resurrection

had yet to appear, but Tolstoy had already provided enough evidence of his blasphemy in the eyes of the Holy Synod, not least in his vicious satire of the thinly disguised Chief Procurator Toporov, and two infamous chapters describing a service held for convicts which subject Orthodox rites to merciless ridicule. Consider, for example, Tolstoy's infamous description of the Holy Eucharist in chapter 39 of Part One:

The essence of the service consisted in the supposition that the bits [of bread] cut up by the priest and put by him into the wine, when manipulated and prayed over in a certain way, turned into the flesh and blood of God. These manipulations consisted in the priest's regularly lifting and holding up his arms, though hampered by the gold cloth sack he had on, then, sinking on to his knees and kissing the table and all that was on it, but chiefly in his taking a cloth by two of its corners and waving it regularly and softly over the silver saucer and golden cup. It was supposed that, at this point, the bread and the wine turned into flesh and blood; therefore, this part of the service was performed with the utmost solemnity.

104

The publication of

Resurrection

brought the question of the excommunication of Tolstoy back to the top of the Holy Synod's agenda.

Tolstoy's rebellion against the Orthodox Church was driven by his perception of its supine position as the mainstay of Russian autocracy. 'The sanctification of political power by Christianity is blasphemy; it is the negation of Christianity,' he had thundered in his 1886 article 'Church and State'. Supporting the state when it went to war was tantamount to the direct sanction of violence, and this was completely untenable as far as he was concerned, for it was a flat contradiction of Christ's teaching, not to mention one of the Ten Commandments. The Orthodox Church

was

vulnerable to Tolstoy's charges, and for the root causes of its moribund state at the end of the nineteenth century we need to look back to the fundamental changes to its autonomous status wrought by Peter the Great. The Russian Orthodox Church was still a very powerful institution when Peter became tsar in 1682, but his determination to forestall any challenge to his autocratic powers led him to take the momentous decision not to replace Patriarch Adrian after his death in 1700. Instead he placed the Church under the jurisdiction of a newly created department of state, the 'Most Holy Synod', which was established in the secular capital of St Petersburg in 1721 to replace the Patriarchate in 'Holy Mother Moscow'. Overseen by a lay chief procurator, whose title in Russian -

Ober-prokurator

- betrays the German Protestant origins of Peter's reformist ideas, the Russian Orthodox Church now became for many simply a tool of the government. Peter introduced formal seminary training to Russia in order to raise standards, but he also reduced the large number of Orthodox clergy, only a third of whom were actually ordained and had received some form of education. Peter's organisation of the state into a hierarchy of service ranks effectively also created a caste system in Russia which separated the clergy from all other classes and made it more or less hereditary, because only the sons of priests were eligible to enter seminaries and train for the priesthood.

105

Most clergy were very poor. They received no salary and were dependent for their livelihood (and that of their often numerous families) on the small sums offered by parishioners in return for the performance of church offices. This was only slightly augmented by the income from farming the small plot of land attached to their parish, so their standard of living was often scarcely better than the average peasant. Chekhov's story 'A Nightmare', written in 1886, describes the embarrassment of a conscientious young priest who is too poor even to be able to offer tea to a visitor. His church is as shabby as his ill-fitting, patched cassock and his house, which is described as being 'no different from the peasant izbas, except that the straw on the roof was a bit more even, and there were little white curtains in the windows'.

106

It is quite a different picture from the usual portrayal in English fiction of the country vicar in his comfortable parsonage, a respected and educated member of the community, and socially inferior only to the local squire. The status of most rural Russian priests, who depended on the peasantry for their basic income, remained very low.

The moral authority of the clergy had steadily eroded over the course of the nineteenth century for understandable reasons. Reliant on assistance from the local peasants in tilling their land, parish priests were understandably disinclined to offend them by refusing their hospitality during icon processions, or by proffering unwelcome moral reproof. The clergy often found themselves equally compromised, for different reasons, when it came to their relations with members of the nobility. Priests found themselves having to pander to the whims of despotic, lawless landowners by carrying out forced marriages or burials of serfs who had died in suspicious circumstances. The overall result of Peter the Great's 'reform' was a highly conservative Church with no interest in doctrinal development, and a demoralised and corrupt clergy which was little respected.

107

The publication abroad in 1858 of a frank exposure of the realities of Russian parish life written by a priest hopeful of change created a sensation when it was illicitly read in Russia on the eve of the Great Reforms.

108

Attempts were made in the late 1860s to improve the church education system (in 1863 seminary graduates were allowed for the first time to go to university, and in 1864 children of clergy were allowed the privilege of attending a state lycée), but the reforms went no further after the seminaries became hotbeds of revolutionary activity.

109

Against such a background, the rise in spiritual prestige of the Optina Pustyn Monastery becomes clearer: by reviving the Hesychast traditions of the Church Fathers, its elders were able to separate themselves from the tainted world of ecclesiastical officialdom.

At the end of the nineteenth century the Russian Orthodox Church certainly felt embattled. The legendary piety of the peasantry expressed itself more in ritual observance of fasts and processions than in attendance at church, its acquaintance with the Scriptures severely restricted by the archaic Church Slavonic which remained the ecclesiastical language of both the Bible and all services.

110

There were already about 180 fast days of differing severity in the Orthodox calendar, but it was quite common for peasants to observe extra fasting days. One old woman confessed to her priest that she had eaten forbidden food on a fast day: radishes whose seeds had been soaked in milk before planting. Many peasants regarded it as sinful to drink tea with sugar on fast days, as they not only regarded tea as 'semi-sinful', but thought that sugar was made of animal bones (dog bones, in fact). There were even some fiercely ascetic peasants who regarded mother's milk as sinful. The Church had also long before ceased to be looked up to as a spiritual authority by the intelligentsia, whose more radical members typically tended to see themselves as morally superior to the clergy, while the aristocracy tended to be apathetic, and their religious devotions merely notional. This is why Protestant Evangelists like Lord Radstock who championed private Bible study made great inroads in high-society circles frequented by people like Chertkov's mother, Elizaveta Ivanovna. By resisting the production of modern Russian translations of the Bible for so long, the Church played its own part in sustaining the rich world of superstitions which the Russian people lived by. Fearing that ordinary believers might make their own erroneous interpretations, and challenge its authority, it was only in 1876 that the Synod officially approved a translation from Church Slavonic into the modern vernacular as mentioned earlier. Even then it tried to control access, but by the end of the nineteenth century about a million copies had been successfully distributed by Russian and foreign religious groups.

111