Tolstoy (5 page)

Authors: Rosamund Bartlett

Ilya Andreyevich was hospitable and generous, but not terribly well educated: when he parted from his wife for the first time in twenty years in 1813, he wrote her a letter riddled with spelling mistakes, and almost totally lacking in punctuation. A brief extract might be rendered in English thus: 'Sadd very sadd my dear friend Countess Pelageya Nikolayevna to congratulate you on your absent name-day for the first time in my life but whatcanbe done friend of my heart but necesery to submit to reason.'

26

Pelageya, for her part, spoke better French than Russian, and that was the limit of her education according to her grandson, who bucked the family tradition by acquiring 22,000 volumes for his personal library.

27

Throughout his writing career, Tolstoy pillaged his family history for creative material to use in developing his fictional characters, and it is not hard to see shades of Ilya Andreyevich and Pelageya Nikolayevna behind the august figures of Count and Countess Rostov in

War and Peace.

Tolstoy actually named his grandfather in his early drafts, referring to him as 'kind and stupid'. His subsequent notes for the character of Count Ilya Rostov also correspond very closely to Ilya Andreyevich, who was also a stalwart of the English Club in Moscow. Tolstoy's account of the lavish dinner Count Rostov hosts there in

War and Peace

is based on sources describing the dinner for 300 which Ilya Andreyevich hosted in 1806 in honour of Bagration's defeat of Napoleon at Schongraben. Ilya Andreyevich was certainly somewhat larger than life. As Tolstoy has recorded, his penchant for placing large bets at games of whist and ombre without being actually able to play, his readiness to give money to anyone who asked him for a loan, and his extravagant lifestyle eventually led to him becoming mired in debt, and in 1815 he was forced to take a job.

The card-playing, and consequently the debts, continued during the five undistinguished years that Ilya Andreyevich served as governor of Kazan, and a succession of poor business deals further increased his debt to 500,000 roubles by 1819. In February 1820 he was dismissed from his post on charges of corruption (which were probably trumped-up — it seems to have been his wife who secretly took bribes). Ilya Andreyevich never recovered from this blow, and he died within the month. Tolstoy inherited his grandfather's gambling habit, and his habit of staking and losing large sums, but he was fortunately able to curb both by the time he got married.

Tolstoy's father, Nikolay Ilyich, born in 1794, was the eldest of Ilya Andreyevich's and Pelageya Nikolayevna's four sons, and very different. When surveying his dismal financial prospects, Ilya Andreyevich realised his son would probably have to work for his living, and so he enrolled Nikolay in the civil service when he was six years old. This meant that when he reached sixteen, he automatically received the rank of collegiate registrar, which placed him on the bottom rung of the civil service ladder. In keeping with his kindly character, Ilya Andreyevich did not beat his children, which was highly unusual, as even the children of the imperial family were subject to corporal punishment at this time. Otherwise, Tolstoy's father had a fairly conventional upbringing for a Russian nobleman in early nineteeth-century Russia. When he was fifteen his aunt gave him Afanasy Petrov to be his personal servant, and the following year his parents gave him a peasant girl for his 'health', as it was euphemistically put at the time. This resulted in the birth of Mishenka, Tolstoy's illegitimate brother, who was trained to work in the postal service, but then apparently 'lost his way'. Tolstoy later found it disconcerting to encounter this poverty-stricken elder brother who was more like their father than any of them.

28

He too would in turn have an illegitimate son, whom his children felt resembled him more closely than they did.

When Napoleon invaded Russia in 1812, Nikolay Ilyich Tolstoy naturally left the civil service to join the army, fighting with distinction before being taken captive by the French. He was unable to afford to serve long in the prestigious and costly Cavalry Guards regiment to which he was transferred when he returned to St Petersburg in 1814, however, and then a combination of disillusionment with the military, ill-health and his father's parlous financial situation led him to resign his commission. Since civil servants could not be sent to debtors' prison, Nikolay Ilyich was obliged to take a job, and this became particularly necessary after the death of his father in 1820 left him as the sole provider for his sybaritic, spoiled mother, unmarried sister and cousin. After all the debts had been paid off, the family could afford only to rent a small flat in Moscow. When Tolstoy describes the position Nikolay Rostov finds himself in after the death of the old count in

War and Peace,

he is essentially telling the story of his father, who in 1821 took up a very minor appointment in Moscow's military bureaucracy. The magic solution for Tolstoy's father, as for Nikolay Rostov, was a rich bride. In the novel she appears as Princess Maria Bolkonskaya; in real life she was Princess Maria Volkonskaya. It was through Maria Volkonskaya that Nikolay Ilyich's family came to be connected with Yasnaya Polyana, the country estate which would be irrevocably linked to Tolstoy's name.

Tolstoy's family pedigree meant a great deal to him. The passage in Part Two of

Anna Karenina

in which the old-world Russian noble Levin scoffs at nouveau riche aristocrats like Vronsky, who lack breeding and cannot point back to three or four generations, expresses a fair degree of his own snobbery. Also very telling is Levin's contempt for the merchants he has to deal with — the up-and-coming Russian middle class. The aristocratic Tolstoy also had no time for merchants, and the fact that he invariably chose nobles or peasants to be his artistic heroes says a lot about his prejudices — he regarded the peasantry as the 'best class' in Russia. Compared to the Volkonskys, who were descended from the legendary Scandinavian settler Ryurik, the ninth-century founder of Russia, the Tolstoys were actually mere parvenus as a noble family. Tolstoy's maternal ancestors came from some of the most venerable and distinguished families in Russia, but his paternal lineage did not actually go back all that far when compared with some of the great families of western Europe. As a Tolstoy, he was a count, but this was a title imported from Germany by Peter the Great in the eighteenth century, along with that of baron, as part of his Europeanisation programme. These titles, which were a reward for service, furthermore kept their original German names,

Graf

and

Baron.

The Russian tradition of each child inheriting the family title, rather than just the eldest son, meant that there were soon hundreds of counts and barons mingling with the old-world Russian princes and princesses.

Tolstoy's mother Princess Maria Volkonskaya could trace her roots back at least to the thirteenth century, when one of her early ancestors was involved in altercations with the Mongol overlords of old Rus. A century later the family took its surname from the Volkona river in the area near Kaluga and Tula where they had lands. In 1763, when he retired from the army, Tolstoy's maternal great-grandfather Major General Sergey Volkonsky bought a share of the Yasnaya Polyana property, south of Tula. Later he bought out the other five part-owners. Yasnaya Polyana, meaning 'Clear Glade', received its name for a very specific reason. In the sixteenth century, when the Muscovite state needed to stave off attacks from nomadic invaders such as the Crimean Tatars, it was able to make the most of a series of natural fortifications along its southern borders in the form of forests and rivers. Vulnerable border areas were strengthened by cutting down trees to form a solid barricade, known as a

zaseka.

The Kozlova Zaseka (named after a military leader called Kozlov) ran for several hundred miles, with clearings at various points which had gateways and access roads. Yasnaya Polyana was located in one of these clearings. It was originally called 'Yasennaya Polyana', because ash trees (

yaseni

) once grew there.

29

Tolstoy's grandfather Nikolay Sergeyevich Volkonsky (1753–1821) inherited Yasnaya Polyana in 1784, and it was he who transformed it from a fairly ordinary piece of land into a carefully landscaped estate, complete with ponds, gardens, paths and imposing manor house when he retired from the army in 1799. Until the age of forty-six, Nikolay Sergeyevich had served in the army, having been signed up for military service when he was six. He was a guards captain in Catherine the Great's retinue when she met Emperor Joseph II at Mogilev in 1780, and fought in the two victorious Russo-Turkish Wars which took place during her reign. After serving briefly as Russian ambassador in Berlin, he accompanied his victorious sovereign on her triumphant tour of the Crimea in 1787 and he was promoted to brigadier and then general-in-chief. In 1794 he was suddenly sent on compulsory leave for two years. According to Tolstoy family lore, this was because Volkonsky had refused to marry Varvara von Engelgardt, the niece and mistress of Prince Potemkin, the great favourite of Catherine the Great. Volkonsky's brilliant career now came to a sudden halt, and he was more or less sent into exile by being appointed military governor in distant Arkhangelsk. Tolstoy greatly admired his grandfather's feistiness, and he clearly enjoyed reproducing Nikolay Sergeyevich's alleged reaction to Potemkin's plan in his memoirs ('Why does he think I am going to marry his wh...'). It was a story he loved to recount to his guests, and he even upbraided two early biographers for omitting it from their manuscripts.

30

The truth was, as usual, far more prosaic, as Potemkin had died in 1791 and Volkonsky was not posted to Arkhangelsk until 1798, by which time Catherine had been succeeded by her son Paul I. At some point in the late 1780s (information is sparse), Nikolay Sergeyevich appears to have married Princess Ekaterina Trubetskaya (1749—1792) in a marriage of convenience. His wife died at the age of forty-three, leaving a two-year-old daughter, Maria Nikolayevna. This was Tolstoy's mother.

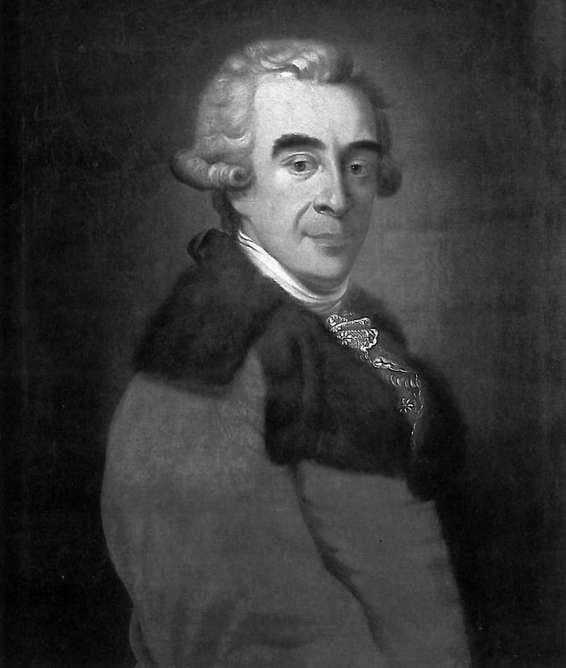

I. Portrait of Tolstoy's maternal grandfather, Nikolay Sergeyevich Volkonsky

It was Paul I's notoriously difficult temperament and constant fault-finding which ultimately prompted Volkonsky to resign permanently from the army in 1799 and retire to his country estate. He never remarried. For the remaining two decades of his life he devoted himself to the upbringing of his beloved daughter Maria, and to creating the idyllic surroundings for them to live in at Yasnaya Polyana which would in turn become instrumental to his grandson's creativity. Volkonsky left one reminder of his military posting in the far north: he built a summer cottage on the banks of the Voronka river, near to Yasnaya Polyana, and named it 'Grumant'. This was the Russian name at that time for Spitsbergen. Volkonsky was governor of Arkhangelsk, the gateway to the Arctic, and also of Spitsbergen, which had originally been discovered by fishermen and hunters from the area near Arkhangelsk. A village grew up around Volkonsky's cottage which was also called Grumant, but the local peasants, for whom this was a very odd-sounding name, renamed it Ugryumy ('Gloomy'). Tolstoy came here as a boy to fish in the pond.

31

The early nineteenth century was the golden age of the Russian country estate, and Nikolay Volkonsky was not alone in wanting to retreat from the official world associated with St Petersburg and the court, and go back to nature. Russian aristocrats had been rediscovering their roots ever since the 1760s, when the nobility began to be progressively freed from the compulsory state service that Peter the Great had introduced in order to drive through his ambitious programme of reform and Europeanisation. With vast swathes of property now in private hands, manor houses began springing up all over the Russian countryside, some of them grand classical mansions, others more humble wooden affairs. The house in which Tolstoy was born was somewhere between the two. The Yasnaya Polyana estate was not quite a tabula rasa when Nikolay Volkonsky took up permanent residence there. In the early eighteenth century, guided by the vogue for straight lines and geometrical precision which characterised the new city of St Petersburg, previous owners had established the main part of the estate in its north-eastern corner, and had constructed two rows of wooden dwellings and a formal garden with lime trees. They had also built a long straight avenue leading from the main house to the entrance of the property, near the main road to Tula.

Volkonsky had grand plans for Yasnaya Polyana, but he needed to find a good architect first, and principal construction work began only after 1810. He decided the main manor house should be at the highest point of the property, facing the south-east. It would be flanked by two identical, two-storey wings, each containing ten rooms. These were built first, with wooden decking leading to the main house. Only the first floor of the manor house was completed in Volkonsky's lifetime. The second storey, which was built in wood to save costs, was added by Tolstoy's father in 1824. It was a house in the classical empire style so beloved in Russia in the early nineteenth century, with thirty-two rooms and a façade graced by an eight-column central portico.