Twilight of the Gods: The Mayan Calendar and the Return of the Extraterrestrials (11 page)

Read Twilight of the Gods: The Mayan Calendar and the Return of the Extraterrestrials Online

Authors: Erich Von Daniken

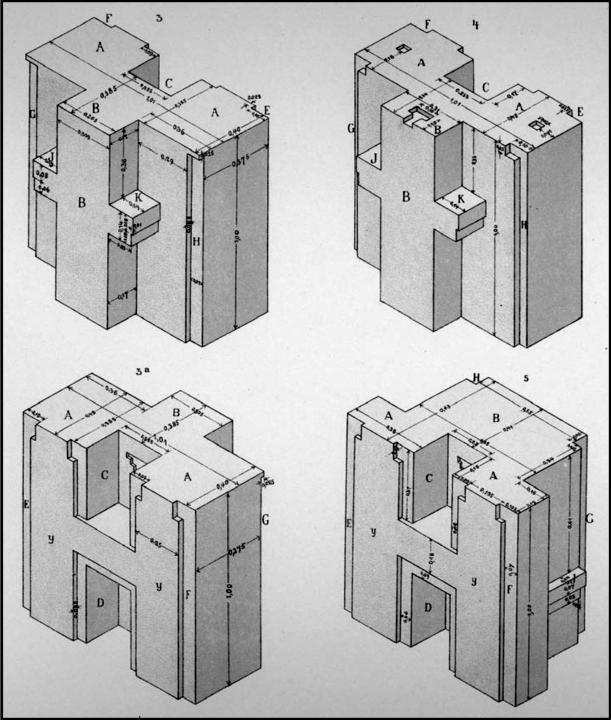

1.18. The precision with which the blocks were cut is simply astounding. Public domain image.

1.19. Could Stone Age craftsmen really have produced such levels of accuracy and consistency?

'ithout Tools or Plans?

'ithout Tools or Plans?

Nowadays, work like this would be carried out using milling machines and high-speed precision drills-water or air cooled. And these tools would be guided by stainless steel templates. Let's not forget that we're talking about hard diorite here. That means the tools that were used must have been harder than the blocks that were being worked. Let's add to this the fact that they would have needed some kind of levers and cranes to lift the preprepared blocks and fit them into each other without any kind of accidents or damage taking place. These blocks fit into each other like safe doors-but with a whole variety of surfaces, rectangles, squares, and levels. Modern concrete elements are utterly primitive compared with the techniques used in Puma Punku. Closing your eyes or just looking the other way doesn't cut the mustard here. Holy Atahualpa help us! Which Stone Age geniuses do they expect us to believe in? This turns their comfortable evolution theory on its head! The gray-green diorite block, with its immaculate smooth finish and its utterly precise, perpendicularly milled groove, is enough to pull the pants down on this Stone Age fairy tale on its ownlet alone the other pieces shown here.

Any claim or assertion is nothing more than an unproven assumption. But as far as Puma Punku is concerned, I'm not claiming anything-I'm talking hard facts. The Aymara, the pre-Incan tribe that allegedly created this masterpiece, cannot be responsible because:

w► The Aymara were a Stone Age people. They could never have transported these heavyweight blocks almost 40 miles.

w► The technology used here is way beyond anything that Stone Age man is known to have had at his disposal.

w► The overall planning and the specifics are based on geometric measurements. High-level architectural skills have been used here.

The builders would have needed to have known the exact stability or brittleness-in other words, the degree of hardness-of the material.

The sheer number of architectural elements would have required a writing system or something equivalent. It's simply not possible to do something like this from memory, and it would have been beyond the planning capacity of our Stone Age geniuses. (These days we plan things like this on computers!)

Archaeologists talk of copper or lead brackets being used to hold the platforms together with a kind of carabiner fastening. This is because copper and lead casting have actually been found in Puma Punku. Heaven only knows why anyone at any time may have used lead or copper in Puma Punku, but it certainly can't have been simply as fastenings for these heavy platforms.

1.20. The slabs were originally held together with fastenings. Image courtesy of Tatjana Ingold, Solothurn, Switzerland.

Lead is a very soft metal, and in its pure form you can scratch it using just your fingernail. Its melting point is 621°Fahrenheit; its boiling point 3,182° Fahrenheit. Lead alloys would be possible, of course, but this assumes some kind of metallurgic expertise. Copper has a hardness grade of 3 (iron is 4.5). None of these soft metals would have been able to hold the incredibly heavy platforms in Puma Punku together. And certainly not when exposed to the kinds of temperature variations that are seen in Bolivia. As early as 1869, Johann Jakob Tschudi wondered:

Even more than by the mere fact that they were actually able to move these blocks, we are astounded by the sheer technical brilliance of the masonry work, especially when one takes into account that the indigenous laborers possessed absolutely no iron tools and that the alloys of copper and tin they had were far too soft to work the granite. [Author's note: Tschudi was wrong in one respect, of course. No granite was used in Puma Punku; it was diorite, which is equally as hard.] How they accompanied this is a mystery. The most plausible view is that they achieved their final polish by rubbing the stone with a fine stone powder or some siliceous plants.63

High-level planning and core boring that did not exist during the Stone Age. Author's own images.

My dear, long-dead compatriot Tschudi: If they had used stone powder or siliceous plants, the workers in Puma Punku would not only have had to rub for hundreds of years to polish the huge stone slabs, but also would have needed precision instruments as the platforms all feature various planes and inclinations.

-he Courage to Be Logical

-he Courage to Be Logical

Something's not quite right in Puma Punku, even if you leave aside Professor Posnansky's dating and ignore the calendars of Dr. Edmund Kiss and Professor Schindler Bellamy (and others!). The working of the stone is enough in itself.

Today, the calendar calculations made by Posnansky, Kiss, and Schindler Bellamy have all been discounted. The well-meaning talk is of academic errors. Horbiger's World Ice Theory has been thrown out, today's moon is not repsonsible for the destruction of Tiwanaku, and there were no earlier high cultures. Basta! It's actually true that the Tiwanaku calendar could never be fit to our contemporary calendar-these days you would say the data are just not compatible. The industrious information collectors Posnansky, Kiss, and Schindler Bellamy all knew that. Their calendar had different months, days, and hours than ours. (Just as an aside: The Maya calendar system (see Chapter 4) consists of a number of different calenders that mesh like cogwheels. Thus the "God Calendar"-also known as the "Tzolk'in"- consisted of 260 days. The 260-day calendar is, however, utterly useless for the seasons of the Earth. It's no good for sowing or harvesting, winter or spring. And yet it existed. So which planet was it good for?) As far as the Tiwanaku calendar is concerned, there remains one key question: Why is it, then, that despite this every single one of the more than one thousand tiny details on the statue the Great Idol corresponds with one another? As far as Edmund Kiss's year is concerned, we're talking about a year of 12 months at 24 days-except February and March with 25-and days with 30 hours of 22 minutes each. Well, the question can't be answered by looking at our calendar! Kiss's calculations don't fit to our calendar-but they certainly do fit to the other one. Who knows then with any certainty which calendar would have been valid before the last ice age? We deny the existence of any civilization before the last ice age-ergo the Tiwanaku calendar is wrong. And in the process, we blindly sweep the geological facts under the carpet. Are we not just making it too easy for ourselves?

The latest variation on the Tiwanaku calendar comes from Jorge Miranda-Luizaga, who at least is a Bolivian and knows both the culture and the language of his countrymen. He approaches the Tiwanaku calendar from the perspective of the Aymara, whose language he speaks fluently. The result is a practical calendar that repeats itself year for year and has its roots in the religious cultures of the Aymara.64 Maybe Luizaga's solution is the only correct one; I can't say with any certainty. I can judge the technology, the planning, the transport, and the architectural draftsmanship that have been used to create the blocks in Puma Punku. And that certainly doesn't fit in with the former Aymara tribe. And this brings up another question that has been completely ignored in all of the literature on Tiwanaku: Why on earth did a Stone Age culture actually need such precisely calculated and perfectly smoothed blocks like those that can still be seen in Puma Punku?

For us, the term StoneAge refers generally to a people without metal tools. Stone Age is clearly a highly flexible concept, because the Stone Age is not an age in the sense that it fits in with any global calendar. Depending on geographical location, the Stone Age was 4000 BC oramong the South Sea folk-500 AD. In Brazil's Upper Amazon region there are still Stone Age tribes living today.

When a Stone Age people decide to erect a large building they somehow manage to drag, jockey, or tow the blocks to their chosen location and pile them up on top of each other using whatever methods are on hand. To make sure the walls don't collapse, they use pins and mortises-a kind of key and lock-that need to be chiseled or hollowed out. They never use the kind of engineering arts witnessed in Puma Punku. Are you getting the picture yet?