Twilight of the Gods: The Mayan Calendar and the Return of the Extraterrestrials (7 page)

Read Twilight of the Gods: The Mayan Calendar and the Return of the Extraterrestrials Online

Authors: Erich Von Daniken

The astonishment and wonder of those men who stood before the ruins of Tiwanaku all those centuries ago also left later visitors shaking their heads in awe and reverence. But that wasn't all there was to see: Another part of the Tiwanaku complex consists of a series of inexplicable monster-sized stone blocks, known as Puma Punku. They are situated just a few miles southwest of Tiwanaku-and I would like to tell you now: if you ever visit Tiwanaku, don't miss Puma Punku! Don't be put off by any excuses from tired tour guides. Whereas Tiwanaku has, to a small extent, been reconstructed, this is not possible in Puma Punku. The stone platforms are simply too heavy and too huge. Thanks to Horbiger's World Ice Theory and the racist Nazi philosophies of that time, Puma Punku has been scandalously ignored in the modern archaeological literature. This is how South America's mysterious Puma Punku is treated in one sumptuous anthology-in just a couple of lines of text:

In the southwestern corner of Tiwanaku stand the large pyramids known as Puma Punku. Their upper platforms form two flat areas at different heights, both of which can be reached by ascending several flights of steps. On one of the platforms a temple may have stood, with three large portals built in the style of the sun gate.3"

That's not just meager; it's also wrong. Puma Punku was never a pyramid and doesn't present itself as one today either, and the socalled "sun gate"-well that's another subject entirely and has nothing to do with the platforms of Puma Punku. (I'll get back to that later.)

In the first half of the 19th century, French paleontologist Alice Charles Victor d'Orbigny (1802-1857) traveled to South America. In 1833, he stood before the ruins of Puma Punku and reported on the "mighty portals that stand on horizontal stone slabs."39 He measured the length of one of the uninterrupted platforms as 131 feet. These days, however, there are no more interconnected slabs: They are all broken, smashed, or simply ravaged by time. Despite the fact that the Bolivian Army was still using the slabs at Puma Punku for its target practise right up until the 1940s, the stones that remain are still sufficient to leave you breathless. In 1869, Swiss travel writer Johann Jakob von Tschudi stumbled over the ruins of Puma Punku and wrote: "On the way to Puma Punku, we came upon a field with a strange monolith, around 5 feet high and roughly 5.5 feet wide. At its base, it is around 2 feet thick, and at its peak 1.5 feet. It features two row of slots or compartments. The monolith is known as El Escritorio, the desk.""'

1.5. A view of the so-called desk. Author's own image.

Whoever it was that dubbed this block "the desk"-because the various compartments do actually remind you of drawers-was barking up the wrong tree. This block is made of andesite and probably served as a support for stone struts. Even as a specialist in Stone Age mysteries, Puma Punku always leaves me breathless. And I've been there 16 times! This Puma Punku and neighboring Tiwanaku are a panorama of another culture. Mighty blocks of andesite and diorite (a gray-green plutonic rock that is incredibly hard and resistant to weathering), are strewn around. There is absolutely no granite there. The monoliths have been worked with such a precision, honed and polished as if they had been created in a workshop equipped with modern tools such as stainless steel milling machines and diamond-tipped drills. Exquisitely precise channels, around a quarter of an inch wide and roughly a third of an inch deep, cut at right angles-something that simply would not be possible with Stone Age tools-run over the diorite monoliths. (See image 1.6 on page 48.) Nothing here fits in with the image of a primitive Stone Age culture. Puma Punku was witness to some impressive hightech-and that can be proved.

Even before Hans Horbiger started harassing the scientific community with his World Ice Theory, two other German scientists visited Tiwanaku and Puma Punku. Max Uhle (1856-1944) was an archaeologist. He is known as the "Father of Peruvian Archaeology." He met geologist and explorer Alphons Stiibel (1835-1904) at the Royal Zoological and Anthropological-Ethnographical Museum in Dresden. The two learned men were soon friends and colleagues and, in 1892, they published an incomparable standard work: Die Ruinenstatte von Tiahuanaco im Hochlande des alten Peru (The Ruins of Tiahuanaco in the Highlands of Ancient Peru).4' This work, which is only to be found in the larger libraries these days and is usually not lent out, is 23 inches tall and 15 inches wide, and weighs around 22 pounds! Alphons Stiibel noted the precise measurements that they had made in Tiwanaku and Puma Punku, and the archaeologist Max Uhle carefully collected the entire canon of existing writings on the subject of the mysterious ruins. His text is filled with footnotes, notices, and remarks.

1.6. An extremely fine groove runs over the polished diorite block. Author's own image.

Even back then, Tiwanaku lay in ruins. Plundered and cannibalized by robbers and state organizations that transported the perfectly polished blocks off to goodness-knows-where and used them to build houses. This is where, for example, the entire raw material for the village church in Tiwanaku came from, as well as its enclosure wall and the courtyards all around. Monoliths were smashed, precisely worked blocks were converted, and millennia-old columns were adapted to fit in with the church's architecture. So it's hardly surprising that today's reconstruction work in Tiwanaku is only able to give hints of the site's former glories. Nevertheless, Stiibel was able to measure a rectangle 394 feet long (from north to south) and 371 feet wide (east to west). At the front of this rectangle stood a half-broken gateway made of lightgray, andesitic lava, 9.9 feet high, 12.5 feet wide, and nearly 20 inches thick. It is known today as the "Gateway of the Sun." Chiseled into the stone are 48 winged beings flanking a main figure on the left and right. Max Uhle wrote:

"In them [the winged beings; author's addition] we see the most precious legacy of a long-forgotten epoch in religious history.... The mythology in this depiction reveals itself in the wings of the beings that surround the figure in the middle.... And this central figure, too, can be nothing less than some kind of divine being, not least because of the corona surrounding it and the other wondrous signs. It is the sovereign God, to whom homage is being paid by a host of winged, heavenly servants. It almost seems as though the frieze running along the bottom was intended to transpose this homage scene from the Earth onto a heavenly setting....42

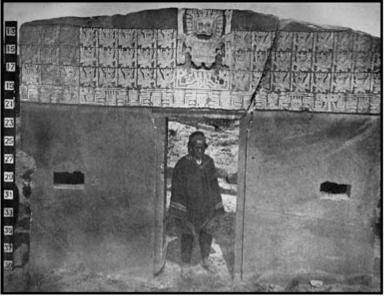

1.7. The front side of the Gateway of the Sun, from around 1910. Public domain image.

This spontaneous interpretation of the sun gate comes from the year 1877. All of the following academics of that epoch, such as Professor Arthur Posnansky, Dr. Edmund Kiss, and Dr. Hans Schindler Bellamy, analyzed the figures on the sun gate and assumed that they represented the most phenomenal calendar in the world. (That's another thing I'll come back to later.)

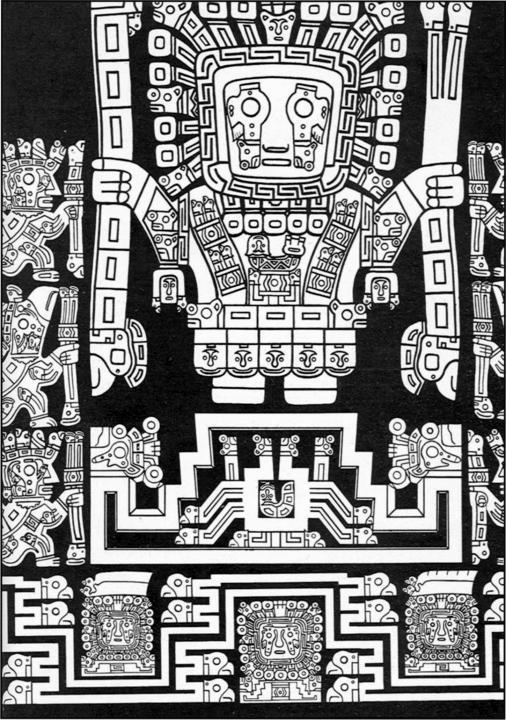

1.8. An accurate drawing of the central figure, from around 1910. Public domain image.

Stiihle and Uhle were astonished by the quality of the stone material used at Tiwanaku and Puma Punku. I quote:

The types of andesite worked here display such a degree of hardness and durability that we must surely categorize them as some of most difficult of all to work.... Bearing in mind the characteristics of the majority of the worked material, we are faced with not only an architectural but also a technical problem here at the site of the ruins. It would seem that the quality of the work here is out of all proportion to the technical means available to the ancient Peruvians.43

These sentences come from Alphons Stiibel, a geologist by trade and an expert who-we can be fairly sure-was well acquainted with the degree of hardness of the stones. Diorite-for example-a graygreen plutonic rock, has a hardness grade of 8. The hardness grade is a measurement of the resistance of a solid body to being penetrated by another body. The hardness of minerals is measured on the Mohs scale (named after Friedrich Mohs, 1773-1839). Any solid material has a lower degree of hardness than a material that can be used to scratch it, and a higher one than any material it can scratch. Take a look at this: Diamonds, the hardest minerals on Earth, have a hardness grade of 10. Diamonds cannot be scratched by stones like granite. In order to work diorite with the kind of unbelievable precision that can be seen in Puma Punku, you would need far more advanced tools than just stone axes. (See image 1.9 on page 52.) The tools that were used must have been at least as hard as, if not harder than, diorite. To maintain anything else is just humbug!

1.9. Every piece is polished. Author's own image.

eeble Excuses

eeble Excuses