Twisted Metal (12 page)

Authors: Tony Ballantyne

‘Why? The reproductive urge is not twisted into the metal of our minds. The Fort Mothers would not build us to think of such things.’

‘Not intentionally perhaps, but the pattern of a mind is a complex thing. For centuries mothers have made minds focused around the reproductive urge. The offspring of those mothers that did not do so never reproduced: they are not with us today. The reproductive urge is so much a pattern of the mind that it is impossible for the Fort Mothers not to incorporate it in some way.’

Maoco O looked down at the pathetic metal shell on the ground.

‘So there are still some women in this fort who will seize on any man and try to make a child with him.’ His words were matter-of-fact.

‘And they lack the full knowledge to properly twist a child,’ answered Maoco L.

‘Interesting. It is a problem that should be addressed.’

‘Agreed. Perhaps after the oncoming difficulty with Artemis is resolved.’

Maoco L picked up the tiny shell. ‘I will pass the mind inside here to the Fort Mothers. Perhaps they can decide who the mother is by looking at the weave of the mind.’

‘A good idea,’ answered Maoco O.

But inside a little voice was speaking.

Why can’t I be as positive inside this fort as I am when I walk outside? Why don’t I feel the same sense of optimism for the future?

The answer filled the dark stone spaces of the fort. The answer was the darkness, and it was given shape by the geometry of the polished stone walls.

Because there is no future. Because there is nothing to be optimistic about, and no reason to wish for such optimism. All there is, is the day that follows this, and the relentless upgrading of smoothly milled bodies as they approach perfection. What else should one require?

Silently, perfectly, seamlessly, Maoco O passed through rooms of identical robots, heading towards his duty station.

The evening dance was due to begin.

Karel

Axel was still young enough to sleep. Karel squatted down before him and gazed into his eyes, wondering where his son had gone to. Karel knew that he had once slept too; he knew that he had once had dreams, back when the metal in his mind was still unfolding and gaining in lifeforce. But that had been long ago and, like every other adult, he had forgotten what it was like. Axel looked so peaceful, following the twists of his own mind, growing new wire, forging new connections and fixing the mind. Karel tried to recall the path he had taken as a child, how he would turn his mind in on itself and descend into sleep. But without success, for the way there was gone.

He heard the front door to the apartment slide open and shut. Susan had returned home at last.

‘Where have you been?’ he asked.

‘Out. Walking. I bought some paint.’ She held up the thin metal case.

‘Let me take that.’ Karel remembered how Susan had been last time they had been getting ready to make a child. So receptive. So creative. She had taken to walking day and night, gazing at the sky, at the sea, at the land. At everything, whether a building, the slope of a pile of gangue, an oddly shaped stone. She was drinking in images and thoughts and concepts, storing up information to be used in the making of a new mind. Too much information, perhaps. She would come home and it would all spill out of her, painted onto the foil leaves of books, scrawled across the walls, twisted into iron and silver. What must it be like to be a woman? he wondered, as he took the metal case and laid it on a table. He took her hand and led her to a chair. There was a shallow foot bath pushed underneath it, already filled with light oil.

‘Sit down,’ he said. He knelt on the floor before her, took one of her feet in his hands and began to pry the segmented casing away from it.

‘Oh, Karel, thank you!’ She sank back into the seat, electromuscles discharging. The plastic-coated sole of the foot came away, and Karel quickly stripped the segmented steel upper.

‘That feels so nice,’ said Susan.

Karel pulled out the oil bath and dropped the upper into it.

‘You’ve got gangue lodged in here,’ he remarked. ‘Where have you been? Into the old city?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did you make it as far as the fort?’

‘Oh, Karel, do the other one too.’

She waved her other foot in his face. He quickly stripped away its covering, then gazed at his wife’s naked feet. Delicate steel bones, shimmering thin electromuscle.

‘You build yourself so well,’ he said.

She gave a relaxed sigh. ‘You’re not so bad yourself.’

He worked on her feet for some time, flexing them, cleaning them, straightening out control rods. He oiled them and slipped the casing back into place.

Then they sat in silence for some time.

‘What are you thinking, Karel?’

Karel looked up into his wife’s eyes.

‘Nothing in particular. Why?’

‘I never know what you’re thinking. Not really. You never let on.’

A distance fell between them.

‘Susan, what’s the matter? Is it the child? It is, isn’t it? Your emotions are all bubbling up, trying to get themselves into order, ready for the making.’

‘Yes! No! Oh, I don’t know. Tell me, Karel, how do you know? All those immigrants. All those people trying to get into Turing City. How do you know they are telling the truth? How do you know that they are who they say they are?’

She leaned forward, her gaze intense, pleading for an answer.

‘How do I

know?

’ echoed Karel. ‘I don’t. Not really. But that’s not the point. They say that they will act in accordance with Turing City’s philosophy; they promise they will weave their children’s minds in that fashion. What more can we ask of them?’

And for a moment, an image of Banjo Macrodocious leaped into his mind.

‘Supposing they’re all lying?’ said Susan. ‘What if they are just saying that so they can come and live here? Wouldn’t we do the same? If our home had been destroyed and we had nowhere else to go?’

‘I’m sure that some of them

are

lying, Susan. Listen, they used to need permits to have children in Segre, back when the Artemisian siege was on and metal was short. But, really, they were just adapting a system that had been used for years in the middle countries. In Stark, robots used to have to pass a mechanical competence test before having children. That’s the price that bought their technical excellence. Robots have been leaving Segre and Bethe and Stark for years to come and live here, simply so they could raise their own children. Were we right to let them in? Well, I think so. Look at what happened: those other countries are conquered, and we are still standing.’

Susan stared at him. She didn’t seem convinced.

‘Are you going to work tomorrow?’ she asked.

‘Yes.’

‘What about the parliament? You’ve heard, haven’t you? Kobuk has managed to get a petition together for parliament to be convened.’

‘Everyone has heard, Susan. Of course I’ll be back for that. But listen, we have Wieners now flocking into the western stations, running from Artemis. We can’t just ignore them, we need to get them processed. And there will be more robots coming. Lots more.’

The golden glow in Susan’s eyes deepened. ‘I can’t help thinking that they’re wasting their time,’ she said, ‘that Artemis will get them sooner rather than later.’ She put her hand to her mouth. ‘Listen to me! I’m talking like a traitor. Karel, I don’t think we should have another child.’

‘That’s just the build-up of emotions,’ said Karel soothingly. ‘You were like this the last time, too.’

‘No I wasn’t and you know it. Karel, there is something waiting for me out there, and I don’t know what it is. My mind isn’t right. I don’t know what to think.’

Karel took her hands. ‘Susan, it will be all right. Trust me.’

He gazed at her. She looked away.

‘Susan? Susan! You do trust me, don’t you?’

She couldn’t look at him. She spoke to the floor.

‘Karel,’ she said, in such a little voice. ‘I don’t really know what’s on your mind. I don’t know how it was made. I don’t think anyone does, not even you.’

She pulled her hands away from his, stood up and walked from the room.

Karel remained where he was.

Thinking.

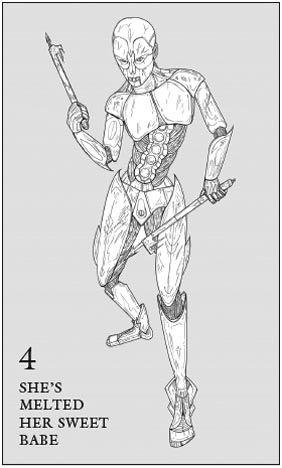

The Cruel Mother

Nyro sat down in the land of Born,

The rain her metal has misted;

And there she has knelt with her own true man,

And a new mind she has twisted.

Smile no so sweet, my Bonnie Babe:

And you smile me so sweet, you’ll smile me dead.

She’s taken out her own little awl

And pulled the metal from her sweet Babe’s head.

She’s lit a fire by the light of the night moon

And there she’s melted her sweet babe in.

As she was going to the forge

She saw a sweet babe in the porch.

Oh, sweet babe, if you were mine

I’d clad you in the metal so fine.

Oh, Mother dear, when I was thine,

You didn’t prove to me so kind.

O cursed mother, this land is full

And it’s here that you will no longer dwell.

O cursed mother, Shull is empty

Go there now, cursed empty shell.

Olam

The feeling of fear in the stadium was electric: it was a static charge building up in the jolting, clanking crowd of robots, threatening to earth itself in a runaway crackle of panic.

‘There’s nothing to worry about,’ said the robot next to Olam. ‘They need us because they’re going straight on to attack Turing City: they’ll have to enlist every robot they can.’

Olam eyed the robot with a dislike that was momentarily stronger than the fear that currently ran through him. The robot was tall, his body plated in whale metal. Clearly one of the Wiener aristocracy. The robot possessed an air of certainty that Olam despised.

‘Why would they want to attack Turing City right away?’ asked a nearby robot. She was a pretty thing but damaged, the panel on her upper thigh cracked. Olam could see electromuscle sparking through the break. ‘Surely they would want to pause and rebuild their strength?’ She was confused, trying to make sense of this sudden reversal in her fortunes.

‘No,’ insisted the tall robot. ‘Doe Menloop knows what’s going on. She told me, Kavan’s leading the Artemis forces now.’

‘Who’s Kavan?’ asked the woman with the damaged leg.

‘Kavan is a folk legend amongst the Artemisians. Kavan is the robot outsider who came to Artemis and proved himself more Artemisian than the Artemisians themselves.’ The tall aristocrat explained all this without a trace of condescension. Well, he would, reflected Olam. His sort would force you to work underground for a lifetime on low wages without any hesitation, and yet would be mortified if they thought they had been unintentionally rude to you. ‘A lot of people have been waiting for Kavan to take control of the army. They expect him to march upon Artemis City itself some day.’

Olam felt moved to speak, but at that moment there was a crackle of static, a whistle from the speakers that studded the iron walls of the stadium, and the anxious noise of the gathered robots died away.

It should have been a beautiful day. A holiday, a day for the people of Wien to take a walk, or go sailing, or to climb the towers of the whale minds. The weather was perfect, the late-autumn sky filling the gaps between the struts and the pillars at the upper reaches of the stadium with bright blue.

Just at that moment Olam fantasized what it would be like to be able to fly. To lift himself out of this cauldron of terrified, pleading robots and to rise up into the air, past the Artemisian guards who patrolled the terraces that looked down over the stadium floor, their guns at the ready. To just rise out of this nightmare and fly to safety . . .